YouTube Version | Podcast Version

Content Warning: This isn’t the sort of piece that’s going to dwell on gory details, but there’s no way to talk about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict and the history of the Jewish people without discussing some pretty horrific things, including genocide, mass murder, rape, torture, and suicide, as well as racism, antisemitism, and antisemitic imagery. Discretion is advised.

Part 1: Beyond the Zero

A screaming comes across the sky. It has happened before, but there is nothing to compare it to now.

It is too late. The Evacuation still proceeds, but it’s all theatre. There are no lights inside the cars. No light anywhere. Above him lift girders old as an iron queen, and glass somewhere far above that would let the light of day through. But it’s night. He’s afraid of the way the glass would fall—soon—it will be a spectacle: the fall of a crystal palace. But coming down in total blackout, without one glint of light, only great invisible crashing.

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon, 1973

In 136 CE, for the third and final time, the Jewish people rebelled against their Roman masters under the leadership of their Messiah, Shimon Bar Kokhba.

For over a thousand years the Jewish people had dwelled here in a land promised to them by God. Great empires have come and gone. They were exiled in Egypt and enslaved, but returned, an event celebrated every year on the holiday of Pasach or Passover. Their kingdom, Israel, was split into two, Israel and Judah. Israel was then destroyed by the Assyrians, while Judah was later conquered by the Babylonians who smashed their holy temple and exiled their people. But the Persians came and the people were restored, and a Second Temple built, an event celebrated every year on the holiday of Purim. The Macedonians arrived, Judah became known by its Greek name Judea, and then Macedonia gave way to the Selucids, from whom the Judeans rebelled and won full independence for the first time in centuries, an event celebrated every year on the holiday of Hanukkah. That lasted less than a hundred years, until the arrival of the Romans.

This happened before, but there was nothing to compare it to now.

The Jews rebelled against the Romans. The Romans slaughtered them and burned down their Second Temple. They rebelled again. And again. And they won. They were righteous, God was on their side, and Bar Kokhba became king of a country he gave the old name, the name of their forefathers. He called it Israel.

Bar Kochba ruled Israel for all of two and half years before the Romans returned. Bar Kochba died, and the Romans went on killing, burning down over a thousand towns and villages and with them their inhabitants. The Jews who weren’t killed or captured and enslaved, starved. Refugees scattered to the corners of the world. Only a few thousand Jews remained in the Promised Land, in remote Galilee.

The Roman emperor Hadrian renamed the land. It would no longer be Judea or Israel, but Palestine, an insult, the Roman word for the Jews’ ancient enemies, the Philistines.

For almost two thousand years, Jews have told this story. Every year we ritually say, “next year in Jerusalem”. Next year we will return to the land of our ancestors.

In 2024, bombs rain down on homes, on shelters, on hospitals. The refugees cannot scatter, they’re not allowed, they have nowhere to go. A people who tell themselves the story of how their ancestors were murdered and starved block trucks carrying food to the starving.

What does this mean? Why shouldn’t Israel destroy its enemies, lay waste to ‘Amalek’ man, woman, and child as in the Holy Scripture, as cited by the Prime Minister? After all, attacking and starving civilian populations has been part of warfare since the beginning, from the Siege of Troy to Leningrad and Hiroshima. Why is this any different?

And of course, it isn’t. Not really.

And that’s the point.

In 1859, Swiss businessman Henry Dunant witnessed the aftermath of a battle in which the wounded and dying lay moaning in the field without medical aid of any kind. Horrified, he went on to found the Red Cross, an international organization for caring for war wounded, and helped organize the First Geneva Convention in 1864, in which member states agreed to allowing and protecting organizations like the Red Cross that help war wounded.

Meanwhile in 1863, the Union Army in the American Civil War adopted the Leiber Code, authored by Fritz Lieber, a German-Jewish American immigrant and legal scholar, which forbid the summary execution, torture, and mistreatment of prisoners of war, one of the first codes of its type.

Over the following decades, more conventions and protocols were agreed to, particularly following the horrors of the Second World War. The Third Geneva Convention, adopted in 1929 and revised in 1949, guarantees protection and safe treatment for prisoners of war (itself updating the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907). The Fourth Geneva Convention, from 1949, guarantees the protection of civilians in time of war. These conventions are now International Law. Grave violations of these laws are called “war crimes”. Those who violate the laws are supposed to face consequences from the larger international community. An International Criminal Court was established in the Hague to try such crimes and other “crimes against humanity”.

The Geneva signatory countries declared, as a group, that intentionally attacking and killing civilians is illegal. Starving civilians is illegal. Torturing and killing prisoners of war is illegal. These are things we’re not supposed to be doing anymore. Because they’re wrong. Because we looked at the mass deaths and genocides of the Second World War and said this is fucked and we’re not doing this anymore.

But there’s a funny thing about war crimes.

Russia is a signatory of the Geneva Conventions.

In 2019, Russia bombed four hospitals in Syria, only four of many hospitals and medical facilities targeted by Russia or the Syrian government over the course of the Syrian Civil War. Russia has also repeatedly bombed civilian encampments there.

In 2022, in Ukraine, Russia bombed a hospital in Mauripol. US president Joe Biden publicly called Russian president Vladimir Putin a war criminal. In 2023, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin for war crimes. And while this is clearly justified (and Russia has continued bombing hospitals in Ukraine as recently as July 8th, 2024, when they bombed a children’s hospital), why did none of this happen when Russia committed war crimes in Syria?

It often seems like for us in the West that things that happen in countries where not-white people live don’t matter or don’t really happen.

People sometimes suggest we wouldn’t care so much about Israel if it wasn’t a Jewish state, and they honestly have a point. If Israel were not a developed country with a mostly white-presenting populace, a populace who seems like us, it might go as under-the-radar as the conflict in Syria. At the same time, there is a good reason why we might talk more about Gaza than we do about Syria or, say, the Rohingya in Myanmar or the Uyghurs in China. Israel is the largest cumulative recipient of US aid in the world, most of which is in the form of grants for the purchasing of American weapons (thus really a subsidy for US arms manufacturers to Israel). Particularly as an American, I think it’s worth asking what exactly Israel is doing with all that money and all those weapons. And if maybe part of the reason some seem to support Israel so strongly against its critics is because the people its killing are the same kind of people who’s killings are being ignored in Syria.

Israel is a signatory of the Geneva Conventions.

In 2024, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for both Israeli and Hamas leaders. Israel denied the allegations, saying it “fights with one of the strictest moral codes in history, while complying with international law and boasting a robust independent judiciary” and further calls the allegations a “blood libel”, in other words a deliberate, antisemitic lie—and we’ll get back to the way the Israeli right meets any criticism with howls of antisemitism later. President Biden denounced the charges, saying there was “no evidence”. The Republican-controlled US House of Representatives voted to sanction the ICC for making these charges (though these sanctions are unlikely to pass the Senate).

And yet, it seems incontrovertible that Israel’s protestations are lies. As per CNN, “At least 20 out of 22 hospitals identified by CNN in northern Gaza were damaged or destroyed in the first two months of Israel’s war against Hamas, from October 7 to December 7” with 14 directly hit. Israel has bombed refugee camps full of civilians. It says that it’s targeting militants who are using civilians as human shields. But, as per the Pace Criminal Justice Blog, “According to article 50(3) of Protocol 1 ****of the Geneva Conventions 1949, even if a civilian population includes some armed people, still they do not lose their civilian status. For example, if militants enter a park filled with civilians – an attack cannot be launched in the park even if intended to only target the militants because under the principle of distinction the civilians ought to be protected.”

And, of course, leaving an active war zone without any functioning medical facilities is its own kind of humanitarian crisis.

Israel has knowingly killed civilians, executed journalists, and kept prisoners in such degraded condition that their limbs required amputation, and the population of Gaza is slowly starving to death while anti-Palestinian activists block and even attack aid trucks. The World Food Program has halted operations in Gaza after repeatedly being attacked by the Israeli Defence Force. This report on how prisoners of the Israelis are being treated—bound immobile, hooded, tortured, fed through a straw—may be one of the most horrific things I’ve ever read. And this is just what gets reported by media in the US, Israel’s greatest supporter. Netanyahu claimed in an address to the United States Congress that almost no civilians have been harmed in Gaza, meanwhile doctors there report daily cases of preteen children who’ve been shot in the head, something that typically only happens when someone is specifically targeted by a shooter.

As of this writing, over 40,000 people are confirmed dead. But that doesn’t really encompass the scale of what’s happened. More than 60% of Gaza’s buildings have been destroyed, and 85% of the population—1.9 million people—have been displaced. The Lancet—the world’s most prestigious medical journal—estimates that the total deaths including the effects of starvation and lack of medical care and shelter could be as high as 186,000 or 8% of the population. And if death continues at this rate, the number could go up to 335,500 by the end of the year.

One objection made by the kind of people who say, “well, what do you expect? this is war,” is “what about the United States?” Didn’t our country and others, for example, kill hundreds of thousands of civilians in Iraq? Remember Abu Ghraib? Shouldn’t George W. Bush and a lot of other people be arrested for war crimes?

The answer is yes. A thousand times yes. Either the idea of war crimes means something or it doesn’t. These rules apply to everyone or they apply to no one. It doesn’t matter if it’s Syria, Israel, Russia, or the United States. That’s how the law is supposed to work.

So how did we get here?

This video is brought to you by my Patreon at Patreon.com/ericrosenfield. I’m apparently celebrating getting into the YouTube Partner Program by releasing a video that’s going to get extra-specially-totally demonitized, so if you appreciate this consider chipping in as little as $1 an episode to get exclusive authors notes, deleted material, and other goodies. You can also support me with a one-time payment at https://ko-fi.com/literatemachine.

Part 2: Une Perm au Casino Hermann Goering

Now what sea is this you have crossed, exactly, and what sea is it you have plunged more than once to the bottom of, alerted, full of adrenalin, but caught really, buffaloed under the epistemologies of these threats that paranoid you so down and out, caught in this steel pot, softening to devitaminized mush inside the soup-stock of your own words, your waste submarine breath? It took the Dreyfus Affair to get the Zionists out and doing finally: what will drive you out of your soup-kettle? Has it already happened? Was it tonight’s attack and deliverance? Will you go to the Heath, and begin your settlement, and wait there for your Director to come?

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon, 1973

According to the Biblical Narrative, some 4,000 years ago God told Abraham to migrate from his home in Chaldea (in modern Iraq) to a land called Canaan on the Western Mediterranean that would be promised to him and his descendants. Those descendants, God told, would number as many as the stars in the sky and their kingdom would stretch from the Nile (in Egypt) to the Euphrates (in modern Iraq).

With his wife’s slave, Abraham had a son named Ishmael, held by both Jewish and Islamic tradition to be the ancestor of the Arab people. With his wife, he had another son named Isaac, who in turn had a son Jacob, whom God renamed Israel.

The Arabs and the Jews are siblings.

Israel’s son Joseph would lead his family to Egypt to escape a famine, where they would ultimately be enslaved. 430 years later, Moses would lead Israel’s decedents, the “Israelite” people, out of Egypt, and his successor Joshua would finally conquer Canaan for them, making it the “Land of Israel”.

None of this actually happened.

At least, there is no corroborating evidence for any of the story I just told. No Egyptian records of Israelite slaves, freed or otherwise, or of the plagues of Moses of the Biblical narrative, no archeological evidence of a mass conquest in the region in the given time period. The walls of Jericho did not fall when Joshua blew his horn.

The oldest recorded mention of Israel is found in the Egyptian Merneptah ****Stele, dating from around 1,200 BCE, that says Egypt conquered a place called Israel. Indeed, we know that Egypt controlled this part of the Eastern Mediterranean until sometime in the 1,100s BCE, when their empire contracted amidst the Great Bronze Age Collapse. A common theory is that during this crisis, there was some kind of revolt among the Israelite underclass, perhaps lead by a figure like Moses, and that after generations of oral history this transformed from them being slaves of Egypt in Israel to them being slaves in Egypt itself.

Palestinians have sometimes claimed that they are actually the descendants of the Canaanite people who were conquered by the Israelites thousands of years ago. While that conquest probably didn’t happen, this isn’t quite as far-fetched as it seems—a genetic study from ancient Canaanite burial sites found genetic links with modern Palestinians. But the funny thing is that they found the same genetic links in modern Jews.

The Palestinians and the Jews are siblings.

In 1099CE, the First Crusade arrived in Palestine and the Crusaders sieged Jerusalem for seven weeks. When they finally breached the walls, they slaughtered tens of thousands of Muslim and Jewish inhabitants.

The Crusaders then set up four states in the Levant. Jews fled for their lives. It’s estimated that of 50,000 Jews living in the region before the Crusade, afterwards only 200 remained, mostly hiding in the mountains of the Upper Galillee.

Trained warrior knights weren’t the first to answer the Pope’s call to retake the Holy Land, though. The first were a rabble of peasants lead by a Priest who rampaged through the Rhineland massacring Jews, murdering “probably one fourth to one third of the Jewish population of Germany and Northern France at the time”.

This group proceeded to make it all the way to the Turkish Seljuk Empire, whose military quickly wiped them out.

Ironically, for most of its history, the Muslim world has been safer for Jews than the Christian one. For Christians, it was doctrine that the Jews were responsible for the death of the Savior and the status of Jews in Christendom essentially depended on the whims of a particular monarch, while in Islam it was established religious law that people of other religions could live in Muslim lands as long as they paid an extra tax and observed some other restrictions. While this did not prevent Jewish oppression by Muslims, and treatment varied considerably across places and times, it did lay open the opportunity for flourishing. Jewish Communities in Muslim Spain, for example, experienced a golden age of prosperity and cultural development, but when Christians retook the peninsula they instituted an Inquisition to forcibly convert and monitor the Jewish inhabitants, and then in 1523 expelled them all anyway.

In Medieval Europe, the Christian church officially outlawed usury, which at that time meant any lending money at interest at all. However, Jews had no such prohibition. Some of the rulers of Europe discovered this loophole could be used to their advantage, because while they couldn’t excessively tax the nobility (on whom their rule depended), they could tax the Jews as much as they wanted, and Jews could loan money to the nobility at interest. Thus the Jews would lend money at interest to the nobles with the monarchs taxing away much of the profits. And Jews were often forbidden from most other trades, thus steering them into the business. And so, during the medieval period, these Jewish money lenders, like most of the merchant strata, did not become very wealthy. On top of this, money lending was something of a fraught position to be in, since if the nobles didn’t pay them back, the Jews might not be able to pay the King’s taxes, with potentially fatal results. Further, this practice gave birth to something known as the “blood libel”.

A rumor began to spread that Jews were kidnapping Christian babies and using their blood to make matzos (despite the Jewish prohibition on consuming blood of any kind). So if you were indebted to a Jewish person and couldn’t or didn’t want to pay them, you could simply dig up the corpse of a baby and claim that you “discovered” it on Jewish land as evidence of their depravity. The Jews might then be rounded up and executed, either by authorities or by a lynch mob while authorities looked the other way, and your debt would disappear.

Sometimes these blood libel accusations would lead to pogroms, riots where Jewish communities were assailed by mobs and in some cases destroyed. Pogroms could also occur during economic downturns, plagues, and other calamities, as Jews were blamed directly or indirectly through their misdeeds and supposed devil worship.

This is the practice that the Netanyahu government is comparing accusations of war crimes to, that pointing out that his government is murdering children is just a new form of blaming Jews for sacrificing gentile babies.

What the f—

Antisemitism created Zionism. The two phenomenon walk hand-in-hand and reflect one another.

Following a series of Jewish expulsions in late Medieval Europe (including England, Hungary, Spain, Portugal, Austria, and Germany) by the mid-16th century, 80% of the world’s Jews lived in Poland, whose rulers found Jewish merchants and money-lenders useful for their economic development. However, in 1795, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Germany ganged up on Poland and divided its territory among themselves.

Russia, which had previously had essentially no Jewish population, suddenly found itself with one of the largest in the world. It responded by restricting Jews to the region that had formerly been part of Poland, which became known as the Pale of Settlement, and strictly curtailing their rights. But during the reign of Tsar Alexander II (1855-1881), some of these restrictions were relaxed and Jews were encouraged to embrace Russian culture and become “Russified” parts of the Russian nation. However, after Tsar Alexander was assassinated, his murder was vaguely blamed on “Jews”, setting off waves of anti-Jewish riots across the Pale (which gave English the Russian word “pogrom”), and the new, viscously antisemitic Tsar Alexander III instigated laws massively curtailing Jewish settlement and occupations, condemning them to poverty.

The history of the Jews in Russia from 1882 to 1917 is one of increasing hostility, scapegoating, and ever more violent pogroms, tacitly approved by the state, which saw the murder of thousands of Jews, rape and assault of many more, and untold amounts of property damage.

Jews who saw themselves as Russian, who wanted to assimilate into Russian society, found themselves now forcefully rejected from it. As Jewish writer Lev Levanda put it, “When I think of what was done to us, how we were taught to love Russia and the Russian word, how we were lured into introducing the Russian language and everything Russian in our home … and how we are now rejected and hounded …. my heart is filled with corroding despair from which there is no escape.”

Meanwhile, in the West, the rise of the Enlightenment saw equal rights granted to Jews for the first time, beginning in the United States upon its founding in 1783 and France in 1789 following the French Revolution. The Enlightenment philosophy of equality under the law that defined the new capitalist nation-state would include Jews.

Capitalism allowed the merchant class to attain real wealth to rival the nobility for essentially the first time, and that included Jewish merchants, with the most famous being the Rothschild banking family beginning in the 1760s. A side product of this, of course, is that the Rothschilds have become the subject of every manner of unsubstantiated conspiracy theory. For some funny reason, gentile banking families including the Welsers whose fortunes go back to the 1500s, or the Oppenheims, Mellons, and Morgans don’t get quite the same attention.

But as nationalism and racism developed over the course of the 19th century, so did antisemitism. The term “antisemitism” itself emerged this century to give the old, Medieval “Jew hatred” a new, more scientific sheen. (Of course, “Arabs” are also semites, and in its original use the term intentionally lumped Jews in with Arabs as people who are not European, though of course now the term almost exclusively refers to prejudice against Jews.)

In France in 1894, Jewish military officer Alfred Dreyfus was framed for treason, causing France’s first wave of pogroms against Jewish communities since 1789, with riots “breaking out in 55 cities”. Meanwhile, openly antisemitic political parties gained traction in the various political legislatures of the region.

The last real attempt by Jews to retake Palestine had occurred in 602CE (while allied with the Persian Sassanids) and while there was always some Jewish presence in Palestine, the population had never really rebounded from the First Crusade. Since then, the notion of a return of the Jews to the Promised Land had taken on a purely religious significance—Jewish diaspora was a punishment from the Lord, and only the Lord would restore the Jewish people through the appearance of the Messiah. Even today a lot of ultra-religious Heredi Jews think the idea of the modern state of Israel is heretical. At least one would-be Messiah had in fact arrived, Sabbathai Zevi, who’d moved to Jerusalem in the 1660s and attracted many followers before getting arrested by the Ottomans and forcibly converted to Islam.

As I talked about in Loki or How Conservatives become Fascists, as Feudalism gave way to Capitalism, a new idea emerged with it: nations. This was the idea that a people were not merely peasants and nobles or Protestants, Catholics, Jews, and Muslims, but distinct people with particular cultural characteristics, and this was folded into the new idea of race, such that people would talk seriously about how, for example, the “English race” was superior to the “Sicilian race” and by the early 20th century would use badly formulated and administered IQ tests to prove it. Thus also emerged the idea that the Jews were themselves a nation and a race, whether or not they actually believed in the religion of Judaism, a sense enhanced by the endless rejection and othering they experienced from the nations all around them.

Nationalism, in turn, was the idea that a distinct “nation” had a right to self-determination, free from interference by other nations—in other words, that a nation should have a nation-state. (This gets conflated in modern English to the point where “nation” now more often simply means “country”, but that’s not how I’m using it in this piece.) But, of course, the Jews didn’t have a state. And where would a state be but, Messiah or no, in the place where the Jews began and to where they’d always dreamed of returning?

There were some early iterations of this; notably, Napolean had rallied Jews into his army in 1799 by promising to restore them to Jerusalem, but had never actually captured it. Another example is how, in 1787, Russian military leader and philosemite Grigory Potemkin formed a Jewish Cavalry regiment with the aim of using them to take Jerusalem as part of his larger goal of conquering the Ottoman Empire, but he died before it could be attempted.

It’s only really in the late 19th century with rising persecution that you start seeing Jewish writers seriously proposing the creation of a new homeland in Palestine, like Moses Hess in 1862, Leon Pinsker in 1882, and most notably Theodor Hertzl in 1896 after which he would form the First Zionist Congress in 1897. (Named after “Zion”, a hill in Jerusalem often used as a synonym for the city and for the proverbial “Land of Israel” as a whole.)

As Herzl announced in his speech at this event, it was antisemitism that had created the movement, without which the Jewish people might have been happily assimilated. “Anti-semitism,” he said, “has given us our strength again. We have returned home… Zionism is the return of the Jews to Judaism even before their return to the Jewish land.” He’d earlier remarked that “Only antisemitism had made Jews of us”.

But most Jews did not want to go to Palestine, at the time a fairly neglected Ottoman backwater, where Jews did not have civil rights and were under constant persecution by local authorities.

Between 1881 and 1914, 2 million Jews left the Russian Empire, the largest Jewish migration in history. Of those more than 1.5 million came to the United States (including members of my own family), which at the time still had open borders for everyone except the Chinese, because racism. Only about 60,000 migrated to the Ottoman Empire, and many of the earliest settlers left within a few years because of the harsh conditions.

During World War I, however, while Britain was at war with the Ottomans and under intensive Zionist lobbying, the British government saw value in drumming up Jewish support and loved the idea of establishing a colonial state in the region under British protection and with a special British relationship. And so they released “The Balfour Declaration”, expressing their support for creating a Jewish “homeland” in Palestine. But to aid an Arab revolt against the Ottomans they’d also promised Arab leader Hussein bin Ali al-Hashemi an independent pan-Arab state after the war, which Hussein at least seemed to think included Palestine. Meanwhile, the British also secretly made plans with France to divide up the region between themselves.

Following the war, the former Ottoman possessions in the Middle East were carved up between Britain and France as “mandates” as established by the new League of Nations to ostensibly cultivate into independent states run by local people. The British set Hussein bin Ali’s son, Faisel al-Hashemi, up as king of Syria (which Faisel assumed included Palestine) only to have the French immediately overthrow him, with the British later making him king of Iraq instead, and giving half of the Palestine mandate to his brother Abdullah to rule as “Transjordan” (now the Kingdom of Jordan). Hussein bin Ali himself, meanwhile, became king of Hejaz but refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, saying he’d been promised a pan-Arab state, not a region carved up into mandates controlled by foreigners and Zionists. The British subsequently backed his overthrow by the Saudi family.

Official oppression of the Jewish minority in Palestine was lifted and Zionist organizations began buying up land in earnest and encouraging Jewish immigration with the cooperation of the British government.

When Jewish settlers had begun arriving in the late 19th century, they’d remarked how welcoming and friendly the local Arabs were, and they’d gotten advice in local agriculture from them, and many of them worked on Jewish farms. However, things changed, particularly following the Balfour Declaration, when the Palestinians realized the Jews had arrived not merely to settle but to take over the place*.*

Zionism is a settler colonial movement. That this statement is controversial now is due to the negative taint that term has gotten over the course of the 20th century. Zionists today will often claim that the Jews can’t be colonizers because we were the indigenous people originally. But as this video by Fredda explains, a people being “indigenous” isn’t about who got there first, it’s about a position in a colonial relationship, about who is doing the settling and who is being settled upon.

In any case, when the Zionist movement began and throughout the Mandate period there was no confusion about what they were doing, with one of the primary Zionist groups called the Palestine Colonization Association and the division of the Palestine Zionist Executive that created new settlements being called the “Colonization Department.”

However, notably for a colonialist movement of the time, the early Zionist movement was predominantly socialist in character, as socialism was very much the dominant political movement among the working classes in Eastern Europe, where most of these Jews came from. “Labor Zionists”, as they were called, like Dov Ber Borochov, imagined their colonialism to be a kind of enlightened socialist form with “nothing in common with the politics of colonial conquest, expansion, and exploitation” that would “assist the Arab population to overcome their primitive standards of civilization and economics”. And yet despite this (condescending and patronizing) ostensible goal, in reality they did precious little to accomplish any assisting the Arab population. For example, instead of inviting them to work on their collective farms, the Labor Zionists forbid non-Jewish labor as standing in the way of Jewish self-sufficiency. Zionists will proudly tell you to this day that up until 1948 they bought all their land in Palestine legally and this is true. But they bought it from wealthy effendis who often lived in other parts of the former empire, and then they evicted the poor Palestinians who actually lived there. And rather than working to improve the infrastructure and schools for the Palestinians, they complained to the British Mandate that too much of their tax money was being spent on them, even though the Zionists were swimming in foreign donations and had the advantage of more sophisticated educations and training. And so it was ironically the British Mandate and the more capitalist Jewish enterprises that actually employed Arab workers that most helped to improve their economic and social conditions.

Now, it’s worth pointing out that at this point it wasn’t even clear what a “Jewish national home” actually meant. There were plenty, like Haim Margolit-Kalvarisky, head of the Palestine Colonization Association, and Herbert Samual, the Jewish-British first High Commissioner of the Mandate of Palestine, who imagined a binational solution with Jews and Palestinians sharing power in a single state. Others imagined simply an autonomous Jewish region within a larger Arab state, like the fleeting Greater Syria of King Faisel. Ahad HaAm, leader of the “Cultural Zionist” (rather than “Political Zionist”) movement, emphasized the need for a gradual approach that would integrate the Jewish people with the local Arabs and worried that when a people come out of oppression directly into power they exhibit “despotic tendencies” themselves, and so any kind of Jewish political power in Palestine should wait until the character of the Jews themselves had changed. Chaim Weizmann, chairman of the World Zionist Organization (and future president of Israel), was emblematic of the dominant, practical approach to the issue, buying up land and building up settlements and businesses In coordination with the Mandatory authority without presupposing entitlement to any more than they could physically claim (though they tried to physically claim as much as they could).

Moreover, fundamentally, there was a sense among the Zionists that they could peacefully buy up land and establish a state with a Jewish majority without the local population doing more than showing gratitude to them for improving the place. Many were thus shocked when anti-Jewish riots broke out in 1920 and 1921. To this day, there is a narrative among Zionists that all they did was peacefully settle in Palestine only to be attacked by the savage Arabs who simply hated Jews, from which point they were justified in defending themselves.

Ironically, the person who saw the situation most clearly was not the Labor Zionist left but Ze’ev Jabontinsky, a man so far right that Benito Mussolini himself once acknowledged him as a fellow Fascist. Jabotinsky was infuriated that the British had given away the Transjordan and felt that the peaceful, gradualist approach of Weizmann was essentially suicidal. “No colonized people ever welcomed their own colonizers,” he wrote. Why would the Arabs consent to having their land overrun and claimed as a sovereign state by foreigners? No one would voluntarily consent to that. Therefore, for the Zionist project to succeed it had to clearly declare its intentions of a state across all of Palestine (including the Transjordan) and create an “Iron Wall” of force to make the local people accept it. Only then could there possibly be peace. Ironically, unlike most of those who would follow him, Jabotinsky was still amenable to a binational solution as long as Jews had a clear majority, making the Palestinians junior partners in the endeavor (once they’d been forced to acquiesce).

Jabotinsky, further, had no patience for socialism or its egalitarian ideals. He declared, “we, the bourgeoisie, the enemies of a supreme police state, the ideologists of individualism… We don’t have to be ashamed, my bourgeois comrades.”

Jobotinsky founded a movement, the Zionist Revisionists. While the Labor Zionists had a militia called the Haganah established (originally) for self-defense, the Revisionists created their own militia, Irgun, that specialized in retribution headed by Jabontinsky’s disciple and protégée, Menachem Begin. Jabotinsky’s follower Abba Ahimeir openly called for a Zionist state modeled on Mussolini’s Italy with Jabotinsky as “el Duce”. The slogan of Ahimir’s faction of Revisionists was “Conquer or Die”.

Still, despite all of this the Jews might have remained a tiny population in Palestine without a great deal of power and the Zionist movement amount to relatively little if global antisemitism hadn’t dramatically changed the situation. In 1924, the United States (under the influence of open eugenicists and white supremacists) decided it had had enough of these Jews and other people from undesirable regions like Asia and Eastern and Southern Europe, and created severe new restrictions and quotas, essentially slashing Jewish immigration to a trickle. This coincided (not coincidentally) with a ratcheting up of antisemitic violence in Europe, particularly rising to a crescendo with the arrival of the Great Depression, which conspiracy theorists (including Hitler) blamed on Jews.

Tens of thousands of Jews began to pour into Palestine. And in many cases, antisemitic organizations and governments were happy to help them go and free their own countries of Jews. The Nazis themselves, following taking power in 1933, shipped 60,000 German Jews to Palestine.

But with an increase in Jews came an increase in Arab resentment, leading to further riots in 1929 and 1933 and a full on revolt from 1936-39 (a revolt inflamed by the release of the British Peel Report, which first proposed splitting the territory into separate Jewish and Palestinian states). By this time, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt had all been given independence. Why shouldn’t Palestine as well—all of Palestine with its Muslim Arab majority?

After each these riots and during the revolt, the British implemented fresh restrictions on Jewish immigration until, finally, with the threat of Arab collaboration with the Fascists, they announced there would be only 75,000 Jewish immigrants permitted over the next five years, after which further immigration would be up to the Palestinians, who’d made it clear they wanted no more Jewish immigration at all. They also forbid new Jewish land purchases, and announced that there would be no Jewish state in Palestine after all.

This, of course, left millions of Jews in Europe with nowhere to go.

With the ramping up of Jewish persecution in Europe as well as Arab hostility in Palestine, over the course of the 30s the dominant vision of Zionism had shifted from gradual integration and potential binationalism to total Jewish independence as the only way to control immigration and ensure Jewish survival.

Ironically, the same Nazis who’d collaborated to send Jews to Palestine were also flooding the Arab world with antisemitic propaganda in order to win the Arabs over against their enemies, whom they implied were controlled by a vast Jewish conspiracy. The notion of a Jewish conspiracy for global domination has no precedent in Islamic or Arab tradition but, like much Arab antisemitism over the last few centuries, comes directly from European influence. The Nazis also funneled money and weapons to Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, the leader of the ‘36-‘39 revolt.

In June 1939, the ocean liner MS St. Louis carrying 900 Jewish refugees arrived in Cuba seeking asylum. They were refused, and were also refused by the United States and Canada. They returned to Europe where most of the passengers were ultimately murdered by the Nazis.

In 1942, the ship SS Struma bound for Palestine with 769 illegal Jewish refugees on board (including 70 children) suffered engine troubles and was forced to dock at Istanbul. The refugees begged the Turkish government to take them in, and were refused. For two months the ship remained at dock, nonfunctioning, with the passengers growing increasingly hungry and desperate. Britain was asked to let the refugees go to Palestine even if they were then detained and sent to Mauritius, where many other illegal refugees to Palestine had been sent. Britain refused. Eventually, the Turkish government simply towed the ship back out to sea, where it stayed for a day, immobile, until it was torpedoed by a Soviet submarine with orders to sink all neutral ships in the Black Sea to deny matériel to the Axis. There was one survivor.

And these were only two examples of many where Jewish refugees desperately tried and failed to escape Europe and died. Indeed the Allied Powers continued refusing to take in refugees even after their governments had concrete reports of the mass exterminations being carried out by the Nazis. Objections included that “There would be German spies among them” and “this would relieve the Germans of their legal burden to support all their inhabitants.” These countries just did not want to deal with floods of Jewish refugees, even if it meant their lives.

In 1940, the Nazis had formulated a plan to ship all their Jews to Madagascar, but were stymied by the British naval blockade.

“Genocide: Was it the Nazis’ Original Plan?”, Yehuda Bauer, 1980

The Nazis wanted to ship away their Jews, if only someone, anyone would have taken them. But failing that, a “final solution” was found to purify their nation-state. As Yehuda Bauer of the Department of Holocaust Studies at Hebrew University wrote in 1980, “mass murder was avoidable because there was a willingness to sell or barter the Jews … [but] the free world was not prepared to buy the Jews.”

And the result was not only the murder of six million Jewish people but the birth of the State of Israel.

Before doing the research for this episode, my idea of how Israel was created went something like this: the UN, feeling so terrible about the Holocaust, divided Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, and then the Arab regions and the surrounding Arab countries attacked the Jewish state which improbably managed to beat them back.

This isn’t quite how it happened.

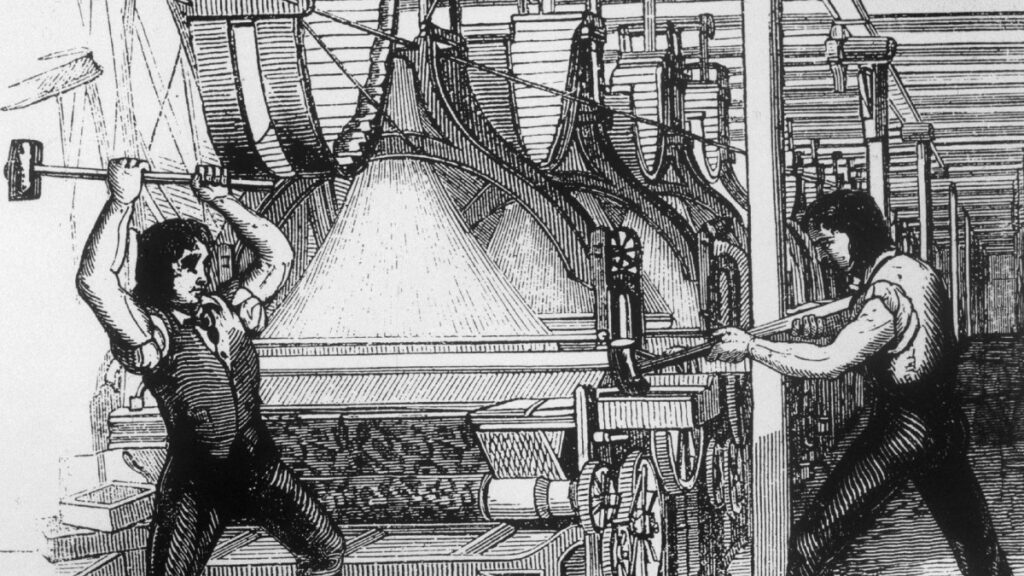

The effectiveness of Arab riots and revolt in convincing the British to change policy reinforced a lesson the Zionists would learn well: violence produces results. Well, the Arabs weren’t the only ones who could inflict violence.

Irgun began carrying out attacks directly on British targets, but paused when the Second World War began and Britain was fighting the Nazis. However, as the war went on, many of Irgun’s ranks decided there was simply too much on the line to allow the British to continue refusing Jewish refugees, broke off into a new militia called Lehi, which actually made overtures to Nazi Germany and Fascist Spain for aid in fighting the British in Palestine. In 1944, they bombed British offices, killing military personnel and police officers, and murdered a British Minister in Cairo.

Once the war ended, hundreds of thousands of Jews were brought to refugee camps in Europe, desperate to immigrate, with Allied countries no more inviting than they’d been before.

Irgun joined Lehi in attacking the British in late 1944 At first, the left-wing Haganah militia fought with the British against Irgun and Lehi. However, with the revelations of the full scope of the Holocaust coming clear as well as a fresh anti-Jewish pogrom in Poland in 1946, Haganah joined in the fight, bombing 10 of the 11 bridges connecting Palestine to its neighbors that year. The next month, Irgun bombed the Administrative Headquarters of the British Mandate in the King David Hotel, killing 91 people. Between 1946 and 1948, Lehi alone carried out over 100 acts of sabotage and murder.

And this is the irony of Israeli independence. The Zionists felt that the only way they could gain independence from a colonial power was through terrorism.

By 1947, the families of British service personnel were ordered returned to England. Remaining non-military personnel lived behind wire-enclosed security zones under a dusk-to-dawn curfew, only exiting under armed escort.

Palestine had become ungovernable, and the British, still reeling from the Second World War, wanted out. So, in desperation of an alternative that wouldn’t lead to further British deaths, they handed the matter over to the United Nations, saying they wanted to end the Mandate.

The United Nations then voted to partition Palestine into Jewish and Palestinian states, giving the Jewish 30% of the population 56% of the land, and the Jews accepted the partition while the Palestinians rejected it. However, the UN included no provisions at all for creating or enforcing the partition, assuming the British would handle it. But to the British at this point, the Zionists were terrorists. Further, the Arab countries under the Arab League had announced that if such a partition was attempted they would invade and had begun massing their militaries on the Palestinian borders.

And so, while the British still confiscated any Jewish weapons that they found, they began simply handing over weapons and military bases to the Palestinians as they pulled out, figuring, it seems, that the problem would “solve itself” soon enough. The Jews would either back down and accept Arab rule or they would fight and be forced to accept Arab rule. (That this might cause another Jewish genocide or at the least another massive refugee crisis doesn’t seem to have bothered them.)

Of course, this isn’t what happened.

Sometimes, Israeli victory against seemingly overwhelming odds is framed as miraculous and even proof of God’s approval. The truth is, it’s easier to understand than you might think.

The Jews in Palestine had spent the last 50 years building up their own quasi-government with multiple regimented militias and clear chains of command.

The Palestinians on the other hand were lead primarily—but not exclusively—by the religious authoritarian Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, and while the Zionists had been collaborating, Haj Amin had warred with his own rivals and moderates, killing 3,000 fellow Palestinians and driving 18,000 out of the country. Indeed, Haj Amin had seen inflaming antisemitic tensions in Palestine as a means of cementing his own power. While the Zionists had worked with the British authorities to set up democratic structures, Haj Amin had made sure the Arabs would boycott any election, and thus prevent even the appearance of collaborating with the Zionists or the British imperialists. The result was that the Palestinians had nothing resembling a government, much less a military. While the Zionists could call people up to fight, the Mufti had no infrastructure for conscription and deployment. The Palestinians could riot and revolt, to be sure, but they couldn’t make war.

Of course, the invading armies of Lebanon, Syria, Transjordan, Iraq, and Egypt could make war. The leaders of those countries, though, didn’t much bother working with each other and often actually worked at cross purposes. Lebanon, Syria, and Transjordan were all content to grab some territory for themselves and sit tight. And as the invading countries bickered during UN-mandated ceasefires, the Israelis were busy bringing in as much matériel as they could from friendly nations like France and Soviet-aligned Czechoslovakia. If the Arab countries had been at all competent and coordinated at the beginning they might have crushed the badly outnumbered and outgunned Israelis. But because they didn’t, the Israelis were able to inflict sufficient damage that these foreign governments decided further hostilities weren’t worth the cost.

Differences in the ability to wage war here also are indicative of the differences between democracies and authoritarian regimes. For Israel, the leaders were responsible to the populace, were fighting for them and answerable to them—in addition to fighting for their lives. Haj Amin, on the other hand, was only answerable to himself, and often refused orders from the Arab League during the war to pursue his own aims. The invading armies, meanwhile were answerable to the whims of their leaders and the top brass and elites they depended on to keep power. Sometimes this meant throwing bodies at the enemy and letting them pile up, since the leader didn’t have to answer to the bodies’ families—for example, some of the Iraqi gunners were found literally chained to their guns to prevent them from fleeing. On the other hand, it also meant their militaries were subject not to the aims of the people (which might be preserving Palestine for the Arab majority) but the aims of the leader (which might be just seizing as much land for their own country as they can). And these fundamental differences would play out in Israeli-Arab conflict in different ways again and again. For a discussion on the differences in how Democracies and authoritarian regimes wage war, see The Dictator’s Handbook (2011) by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith.

And so, while Transjordan kept the West Bank and Egypt kept the Gaza Strip, the rest of Palestine, far more than had been allotted in the UN partition, belonged to Israel.

Which isn’t to say there was no conflict among the Israeli forces, which at first were still divided between the much larger Haganah and the militias of Irgun and Lehi. During the first ceasefire in the midst of the war, Lehi members ambushed UN mediator Folke Bernadotte and murdered him, which infuriated the Israeli leadership who, in response, arrested 400 members of Lehi, essentially abolishing the organization. Then, when a gunfight broke out between Irgun and Haganah over the distribution of arms, Israel arrested many of Irgun’s leaders and distributed the rest of the group throughout Haganah, creating the single military force that would become the IDF.

Huge numbers of Palestinians fled from their homes during the war. Others were forced out by the Israeli military. A number of massacres occurred, most notably in the village of Deir Yassin, where Irgun and Lehi murdered more than 200 people including women and children. While the Israeli government arrested the officers in charge and officially condemned the act, it became useful propaganda, especially when amplified by the Arab media outraged at Jewish atrocities, because afterwards if an Arab community saw the Israeli military coming they would run for their lives. Arab massacres against Jews also occurred, including the Kfar Etzion massacre in which about 127 villagers in a West Bank kibbutz were murdered, including women and children, an event cited by the perpetrators as retribution for Deir Yassin.

In total, about 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from Palestine during the war, an event called by Palestinians the “Nakba”, or “catastrophe” in Arabic. About 160,000 remained in the new state of Israel, where they lived under martial law for two decades, but most were also granted full citizenship.

Immediately following the war, the Arab governments and Palestinian leaders demanded that Israel allow these refugees to return to their homes and property. Newly minted Israeli prime minister David Ben Gurion said, “No”. Israel would not allow “so hostile” a people to return. At the time, Israel offered to financially compensate the Arabs for their land if the Arab nations that had attacked them formally recognized the state of Israel and agreed to a permanent peace, and even then they specified the money would be put in a fund to help resettle the refugees elsewhere. (They did allow around 35,000 Palestinians to return to their homes if they could prove the “main breadwinner” of their family was still on the Israeli side of the border.) The UN issued a resolution (with no enforcement mechanism) that the Palestinians should be allowed to return to their homes. Israel ignored it. As Israeli President Weizmann put it, “What did the world do to prevent [the Holocaust]? Why should their be so much excitement in the UN and the Western capitals about the… Arab refugees?” Population transfers had happened before, after all, notably 2 million displaced war victims transferred between Greece and Turkey after the First World War, and following the Second 900,000 ethnic Germans were forcibly transferred out of the Soviet Block to Germany. Why shouldn’t there be a bit of ethnic cleansing? The Arabs had somewhere to go, the thinking went, the Jews did not.

By 1953, almost all the former Palestinian homes and land had been given to the incoming flood of Jewish immigrants.

How much Palestinians really had somewhere to go, though, was debatable. While many Palestinians had fled throughout the Arab world, the majority had ended up in either Transjordan’s West Bank (the country soon renaming itself simply “Jordan”, reflecting its new status on both sides of the Jordan River) or Egypt’s Gaza strip, both of which had been part of the Mandate. While Jordan granted West Bank residents full Jordanian citizenship and rights, the far larger and wealthier Egypt did not give the Gazans citizenship and forbade them from moving out of the territory into the rest of Egypt. Moreover, neither Egypt nor Jordan used their own funds to assist refugees, relying instead on the United Nations and their Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) to administer camps for them. The only assistance Egypt gave to the Gazans was weapons and military gear to help them attack Israel.

Part 3: In the Zone

One village in Mecklenburg has been taken over by army dogs, Dobermans and Shepherds, each one conditioned to kill on sight any human except the one who trained him. But the trainers are dead men now, or lost. The dogs have gone out in packs, ganged cows in the fields and brought the carcasses miles overland, back to the others. They’ve broken into supply depots Rin-Tin-Tin style and looted K-rations, frozen hamburger, cartons of candy bars. Bodies of neighboring villagers and eager sociologists litter all the approaches to the Hund-Stadt. Nobody can get near it. … If there are lines of power among themselves, loves, loyalties, jealousies, no one knows. Someday G-5 might send in troops. But the dogs may not know of this, may have no German anxieties about encirclement—may be living entirely in the light of the one man-installed reflex: Kill The Stranger. There may be no way of distinguishing it from the other given quantities of their lives—from hunger or thirst or sex. For all they know, kill-the-stranger was born in them.

Gravity’s Rainbow, Thomas Pynchon, 1973

One of the most fascinating and celebrated Israeli institutions is the Kibbutz. The socialists who dominated the early Zionist movement relished the opportunity to create what they imagined was the foundation of a new kind of truly egalitarian society, a model for the world. To this end they founded voluntary collective farms, domains of true democracy where every farmer would have a vote. And the most radical form of these collective farms were Kibbutzim, where the farmers shared possessions in common, all received the same wages regardless of role, and where children lived in group nurseries, freeing both their parents from the burdens of child-rearing, though they’d still see their children at least a few hours a day, and everyone took shifts in the nursery. Woman were considered the equals of men at a time when women didn’t even have the vote in the United States. And in the years of the Mandate, while the older, privately owned farms produced more economic value than the collectives, the collective farms outnumbered them both in the quantity of their output and in the number of people involved in them.

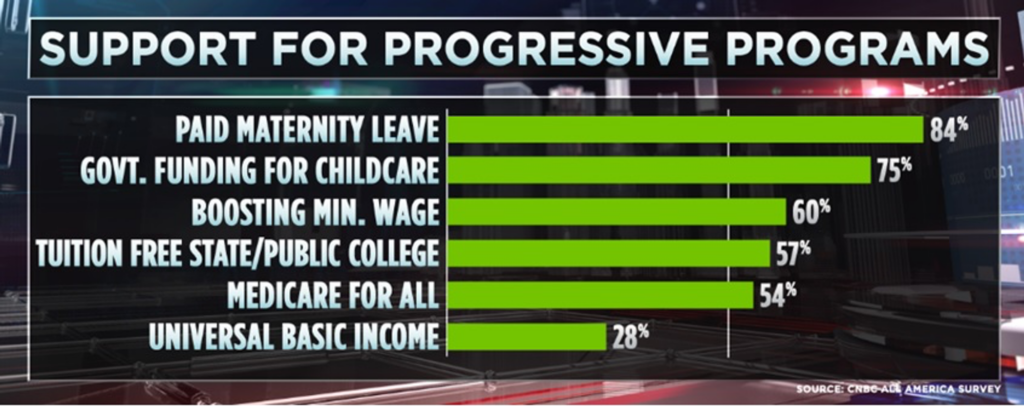

One could imagine how this movement might expand outward into something like Marx envisioned in an early draft of his book about the Paris Commune of 1873, The Civil War in France: an entire economic system made up of egalitarian communes linked by a few functions to manage production and resources so slight it could hardly be called a government, all run in a highly democratic fashion. In other words, actual Marxist Communism (as opposed to the corruption of it that we got in the Soviet Union and the states that copied its model) as discussed in my episode “Star Trek into Socialism”. Further, as the Kibbutzim developed, they began to take up other sorts of businesses. And most Kibbutzim were associated with the Histadrut workers’ union that came to dominate labor in the new country—an organization that quickly grew into far more than a union, but the center of an entire socialized system of economic production. Histadrut opened a chain of retail stores to sell the goods from cooperative farms, and to bulk purchase goods for those farms. It followed this with a workers’ bank to help fund farms and socialist enterprises, a housing company, and ultimately transportation, hotels, restaurants, and a school system. In 1911 it started a health care program for members which by 1930 owned clinics and hospitals with the largest registry of physicians and nurses in Palestine.

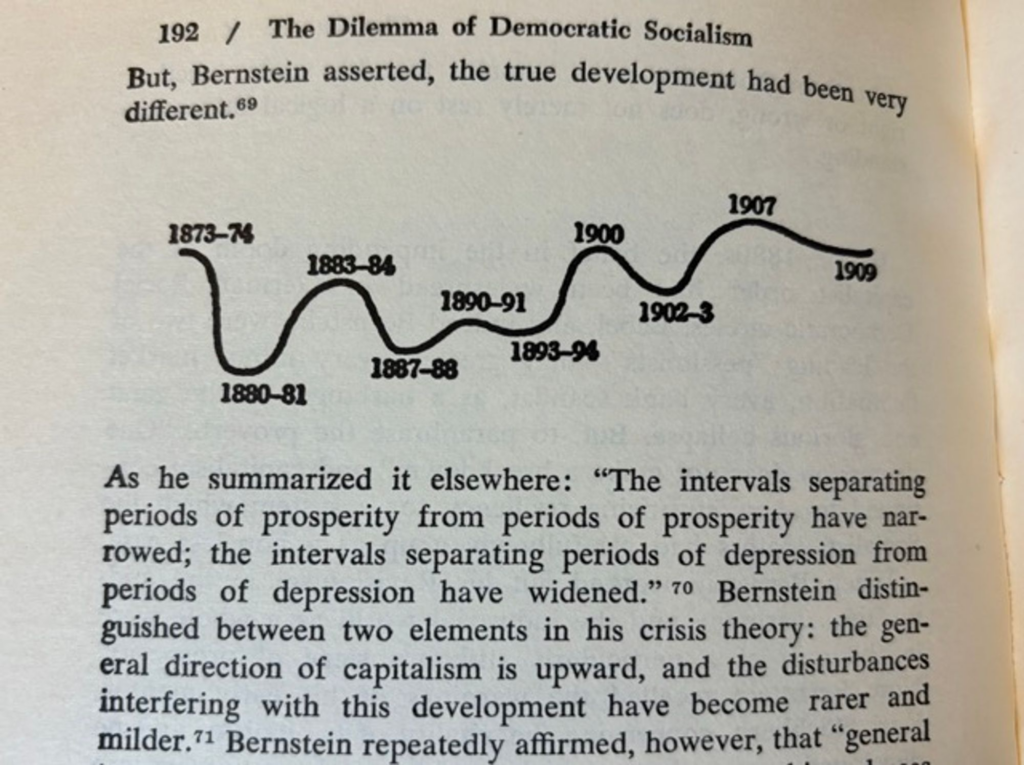

Those of you who watched my episode “How Will Capitalism End?” might recognize this as the Marxist solution to health care that formed the core of Marxists’ objection to nationalized health care in Germany in the 1880s. The Marxists at the time felt that health care should be under control of a workers organization, not a government that didn’t necessarily represent them. Histadrut had actually realized this ideal. And in the years following the creation of the state of Israel, Histadrut enterprises would include banks, newspapers, book publishers, manufacturing firms, import companies, hotels, cement factories, a fishing fleet, the nation’s largest insurance company, and largest building firm. By 1957, Histadrut was the single largest employer in Israel, with a work force of over 100,000 people. And even companies that weren’t managed by Histadrut often had workers unionized by them, giving Histadrut unparalleled power over the economy and demonstrating how the point of socialism wasn’t government control, but worker control.

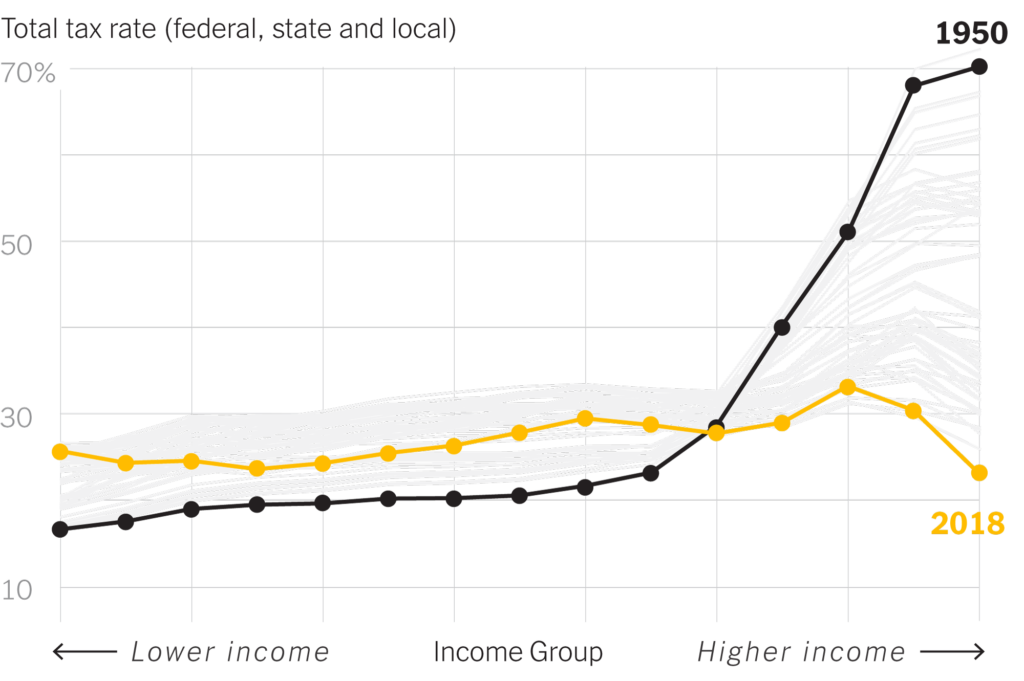

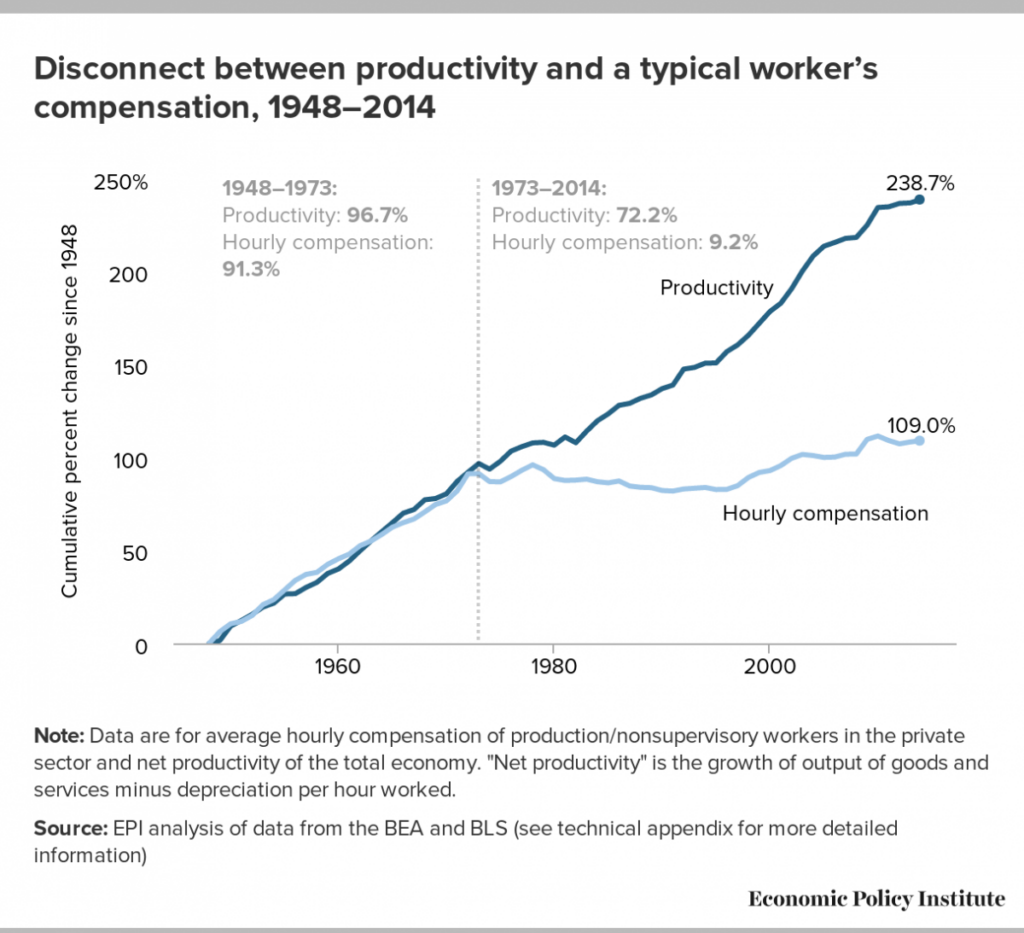

Histadrut, in short, represents actual in-practice democratic socialism to a degree and scale most socialist groups could only dream of, and unlike the mass collective farms of Northern Spain during the Spanish Civil War or the Ukrainian Makhnovshchina during the Russian Civil war, these socialist experiments weren’t short-lived and destroyed from the outside. And the result was that by 1957 Israel had lower wealth inequality than any developed nation outside Scandinavia.

Today, most of this system has been dismantled and privatized. Israel now has higher wealth inequality than any developed country other than the United States, and the poverty rate is one of the highest in the developed world.

So what the hell happened?

I think the answer to that question is intimately tied to another question, which is how could socialism, a political and philosophical system based around egalitarianism, not only reconcile itself with a colonial nationalist project like Zionism, but become, for some time, its chief economic ideology? (It’s worth noting here that the term “National Socialism”, of course, has been permanently poisoned by the Nazis, who were not actually socialist at all (no, not even Gregor Strasser). If you think the Nazis were actually socialists go watch the Three Arrows video “Was Hitler a Socialist?” for an explanation of why that’s obviously wrong.) (It’s also worth noting that there have always been anti-Zionist socialists as well, most notably in the form of the General Jewish Labour Bund (or just “the Bund”), a Jewish socialist movement founded in 1897 that advocated internationalism and the promotion of Jewish civil rights in the countries in which they lived, even while preserving Jewish identity and culture.

As mentioned, for all their talk of “assisting the Arabs”, the Labor Zionists were slow to include Arabs in their actual socialist programs. Arab Israelis were finally admitted to Histadrut in 1960. Arabs were not allowed (and are still not allowed) in most Kibbutzim or other Jewish collective farms, and they weren’t provided with anything like the kind of financial or organizational support as Jewish immigrants new to the country. Large numbers of them worked in Israeli-owned businesses, but were forced into punishingly long commutes because landlords in the Jewish cities wouldn’t rent to them. In other words, though they were citizens and ostensibly had equal rights, Palestinian Israelis formed a discriminated-against underclass within the land where they and their ancestors had resided for centuries.

Still, Israel had proclaimed freedom of religion and creed, and the Palestinians were lawful citizens. The Nakba was behind them, and at least now they could tell themselves they were a modern liberal democracy.

At least, they could until 1967.

On the 10th of June, 1967, Israel declared victory in the six-day war. Once again Israel had faced an existential threat, as Egypt’s president Gamal Nasser had declared his intent to “exterminate the State of Israel for all time” and the Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization had called it a war where he didn’t expect any Israelis to survive. Still, Nasser’s negligent air force hadn’t bothered putting any of the fancy new Soviet MiG jets he’d purchased in protective bunkers, nor did they have a radar system in place to detect incoming aircraft, allowing Israeli jets to swoop in and destroy almost all of them in a single go. The Israeli military had then spent most of the rest of the war chasing the poorly organized Egyptian forces right across the Sinai while Nasser’s generals lied to him about the state of things to save face, and the Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian militaries once again completely failed to coordinate with one another. Israel seized the Sinai Penninsula, more than doubling the geographic size of the country. And they took Gaza and the West Bank as well, including East Jerusalem, plus a defensible chunk of Syria known as the Golan Heights.

The problem, of course, is that there were people in these territories. People who were not Jewish.

At this time, Israel had a population of around 2.8 million, around 300,000 of whom were Palestinian Israeli citizens. Israel offered citizenship to the 7,000 (mostly Druze) Arabs left in the Golan Heights and the 67,000 in East Jerusalem, but refused to do so for the 700,000 in the West Bank and the 400,000 in Gaza. If it had done so, Jews would still be in the majority—around 2.5M vs. 1.5M—however, Palestinians would go from a small minority to being nearly 40% of the citizenry, forming a sizable voting block. Moreover, given demographic trends it wouldn’t be hard to imagine a future in which Arabs actually did outnumber Jews, something that actually happened around 2018. If given citizenship, these Palestinians could then simply vote for representatives who would pass laws making Israel no longer a Jewish state.

There was a moment when Israel might have nipped the issue in the bud. They could’ve simply given the West Bank and Gaza back to Jordan and Egypt respectively, as the UN demanded, and as the Sinai ultimately was. And at first the idea, at least ostensibly, was that the bulk of the territory would be given back as part of bargaining maneuvers; they made it clear to Jordan and Egypt they’d be willing to discuss the return of territory in exchange for concessions, including formal recognition of Israel and free passage through the Suez Canal (which Egypt had always refused and now had somewhat petulantly blocked completely after Israel took possession of its Eastern bank). However, those countries refused to show any compromise with the state of Israel through negotiation. (King Hussain of Jordan may have been mindful of how his predecessor, King Abdullah, had tried to make a compromise with the Israelis and been assassinated for his trouble by a member of the Muslim Brotherhood.)

Meanwhile, Israelis eager to create “facts on the ground” to back up an Israeli annexation, began setting up their own settlements in the West Bank, which the government would inevitably recognize and integrate into Israeli infrastructure. (The first such settlement was the rebuilt Kfar Etzion, the kibbutz that been the subject of a massacre in 1948.) The government would also set up a series of militarized Kibbutzim along the border with Jordan for defense. This despite the fact that creating settlements in occupied territories is itself a violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

And so, Israel found itself governing over a huge number of people to whom it did not grant citizenship, did not have clear pathways to citizenship, did not have equal rights and privileges, and were subject to a fundamentally different set of laws than citizens—tried, for example, exclusively in military courts.

The word we use to describe such a situation is Apartheid, after the system South Africa used to separate its white minority ruling class from its black majority underclass.

And calling it “Apartheid” isn’t actually the radical statement that some defenders of Israel make it out to be. In 2010, for example, former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak admitted, “If this bloc of millions of Palestinians cannot vote, that will be an apartheid state.” The Apartheid system used the disenfranchisement of the majority of its population to maintain South Africa as a white state. Israel uses the disenfranchisement of the majority of its population to maintain Israel as a Jewish state.

While the Labor Zionist government hemmed and hawed about the issue of the occupied territories and made noises about giving some portion of it back, Revisionists were absolutely clear-eyed about their goals. As mentioned, the movement had begun with a maximalist vision of Zionist entitlement that included what became the Kingdom of Jordan. The solution for the Arab residents of the occupied territories was simple: they had to go. Israel had taken in the Jews expelled or who’d fled from Arab countries after all. Why shouldn’t there be another population transfer? The Arabs should be taken in by the other Arab countries.

But how can this be justified? This wasn’t merely preventing people from returning following a messy civil war in which Israel could (and did) claim a fear of their returned Palestinian neighbors. This was external territory Israel had claimed. How could you justify simply removing Palestinians from Palestine to make way for Jews? Including the part of Palestine that was now called “Jordan”?

But for the Revisionists it wasn’t Palestinian territory, in fact it couldn’t possibly be Palestinian territory. Palestinians, you see, don’t exist.

Now, to those not familiar with it, this argument sounds absurd. Obviously there were Arabs in Palestine before 1948 and, indeed, long before the Zionist movement. But the Revisionist point is that these people were not “Palestinians”. There has never been a sovereign country called Palestine. There was a region called Palestine, created by the Romans on what had been Judea and forming part of their province of Syria-Palestina. From there, this region had been passed between Persians, Arabs, Crusaders, Egyptians, Turks and so on for two thousand years. Under the Ottomans, Palestine had been divided between the provinces of Beirut, Damascus, and Jerusalem. There had actually been a period where part of Northern Palestine had been independent, ruled by a Palestinian Arab in rebellion from the Ottomans for a few years in the 1770s. But that hadn’t been a nation as we think of it, in fact it hadn’t even had a name, merely being called the Sheikdom of Zahir al-Umar of the al-Zayadina family, much as the Ottoman Empire was the Empire of the Ottoman family. The Sheik Zahir al-Umar wasn’t realizing some nationalist project to grant his people self-determination based around their shared national identity. He was merely establishing his (and his family’s) personal control over a region. And the people in that region didn’t think of themselves as Palestinians, distinct from other Arabs. And so, the Zionist slogan went, Palestine was “a land without a people for a people without a land”.

But the example of the Zahir al-Umar’s Sheikdom gets at the heart of the problem with this argument. As I talked about in “How Conservatives Become Fascists”, nation-states as we understand them—as a state that represents a distinct people—didn’t exist until a few hundred years ago, and Jewish nationalism didn’t really become a thing until the late 19th century. As historian Eric Hobsbawm pointed out in The Invention of Tradition (1983), “Israeli and Palestinian nationalism or nations must be novel, whatever the historic continuities of Jews or Middle Eastern Muslims, since the very concept of territorial states of the current standard type in their region was barely thought of a century ago, and hardly became a serious prospect before the end of World War I”.

And most nations, in reality, are actually multi-ethnic in some form, not only nations of immigrants like the United States, but any nation less homogenous than, say, North Korea, has different ethnic groups within it, including Israel. There is no contradiction between me being American and me being Jewish. When a French fascist says that black people can’t be “true Frenchmen”, we can point and say that’s racist and wrong. In Israel, though, shockingly for a liberal democracy, the separation of ethnicity from citizenship is not only legal, it’s institutionalized. All Israeli citizens have a separate, officially registered “nationality”, such as “Jew”, “Arab”, or “Druze”.

And despite Israel’s recognition of lapsed or “cultural” Jews implicit in the whole idea of the Jewish people as a nation and not merely a religion, by Israeli law the only way one can become Jewish is through religious conversion (and only Orthodox conversion up until a court ruling in 2021 that permitted other denominations for the first time). One can bemerely culturally Jewish, but one cannot become merely culturally Jewish. And this conversion is one that Palestinians are not permitted, their applications rejected out-of-hand.

The United States of America could grant ostensible equal rights to its underclass of African Americans without endangering its existence as the United States of America—indeed, it could be said to be fulfilling the ideals of its founders, who’d written “all men are created equal” (though the Right have spent decades now trying to claw those rights back). Israel, on the other hand, cannot grant equal rights to the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza without ceasing to be a Jewish state. And this is a problem at the heart of Israel’s conception of nationalism. Any ethnic group can be a citizen of Israel, but a Palestinian can never be part of the “nation” of Israel.

And it’s this that makes Israel not a nation-state by modern definitions, but an ethno-state.

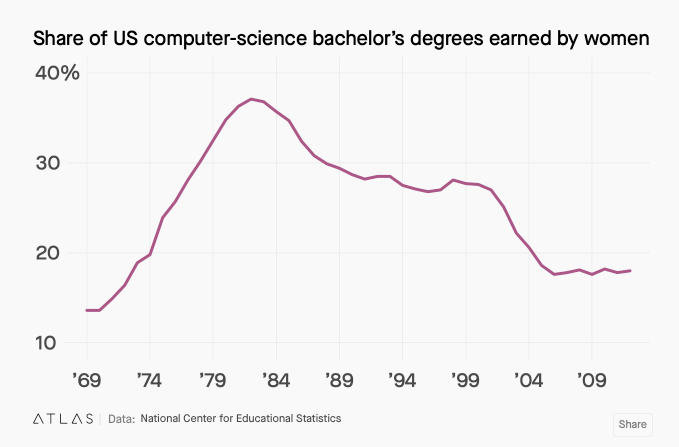

The contradictions at the heart of the Labor Zionist’s project would come to a head and become their undoing not merely when faced with a non-European group they couldn’t assimilate, but when faced with a non-European group they had no choice but to assimilate.

Originally, Zionism was a European Jewish movement. The main ethnic distinction within it at that time was between the more well-off and educated Western European Jews and the much poorer but far more populous Eastern European Jews who were also the ones suffering the most under Russian, and later Polish and German, oppression and the most likely to immigrate to Palestine. During the Holocaust, two thirds of European Jews were murdered, with the brunt taken up by Jews in Eastern Europe. For example, 90% of Polish Jews were murdered, including as far as we know all members of my extended family who were left behind. Further, Jews in the Soviet Union were forbidden to emigrate until the 1970s. Following the establishment of the state of Israel, some 500,000 European Jewish survivors did migrate, but after that, the bulk of the migration came from elsewhere.

Central and Eastern European Jews are traditionally known as “Ashkenazim”, from the Hebrew word for Germany (since most of them had settled in Germanic lands). There were also the Sephardim, Jews who’d been expelled from Spain in the 15th century and mostly resided in North Africa and Turkey, as well as other Jewish groups throughout the Middle East and in communities as far flung as Ethiopia, India, and China. In the years following the creation of Israel, much of the Jewish population in Muslim-majority countries were expelled, evacuated, or fled, frequently in the face of pogroms and ethnic cleansing. Often these were communities that had dated back centuries or millennia. And for the most part they went to the one country that would take them: Israel.

Jews they may have been but culturally they were radically different than the Ashkenazim and more like the people in the countries they came from—demonstrating in some ways the absurdity of envisioning the Jewish people as a coherent “nation” at all. Further, as these Asian and African Jews tended to have larger families, by 1965 the numbers of Asian and African Jews already equaled those of Ashkenazim and would soon overtake them.

The Labor Zionist establishment had viewed this group with characteristic paternal condescension. They created a new term, “Mizrahim”, meaning “Eastern” or “Oriental”, to describe them. Then Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs Golda Meir remarked in 1964, “We have immigrants from Morocco, Libya, Iran, Egypt and other countries with a 16th century level. Shall we be able to elevate these immigrants to a suitable level of civilization?”

Mizrahi Jewish immigrants were given inferior aid to the Ashkenazi immigrants who were thought to be more “desirable” by the establishment. They were routinely discriminated against, and had worse educations and job opportunities. They were taught European history and culture, with their native culture and traditions actively suppressed. As Ben Gurion put it, “Their customs are those of Arabs. … We do not want Israelis to become Arabs.”

While I was working on this piece, our fridge was leaking and we called a repairman, who turned out to be Israeli. We were talking about Queens, where we live, and I mentioned the Bukharian Jews who had historically lived in Uzbekistan in Central Asia but after the fall of the Soviet Union basically entirely decamped for either Israel or Queens. The fridge guy made a disgusted face and went off on some of the most prejudiced language I’ve ever heard, comparing Bukharians to cockroaches who spread everywhere.

I’d heard about the Israeli prejudice against Mizrahi Jews, but I’m not sure I’d ever experienced it first hand.

One notable and frequently remarked feature of the Mizrahi communities is that they vote overwhelmingly for the right-wing Likud, the party dominated by Zionist Revisionists. This has sometimes perplexed observers, who point out that Labor policies are far better for the poor and impoverished, and so these communities are “voting against their own interests”, a phrase that might sound familiar to Americans. Moreover, since the Mizrahi have much more in common both culturally and economically with the Palestinians, one might think they would be in solidarity with them rather than voting for the party most dedicated to their subjugation and eradication.

One explanation sometimes given for this is that these communities have suffered at the hands of Arabs and so disdain them. However, this doesn’t quite hold up to scrutiny, for example, the Jews of Morocco were relatively well-treated before the establishment of Israel.

Unlike the Jews of Europe, though, the Mizrahi did not come from cultures or subcultures that valued secularism, socialism, or universal civil rights. The Azkenazi Labor Zionists were keenly aware of this, of course, and tried to inculcate those things in the new immigrants, but they did so by behaving as if the Mizrahim where backwards children in need of straightening out, and Labor’s socialist ideals didn’t prevent the Mizrahim being worse off economically than the Ashkenazim.

The Revisionists were never much more religious than the Labor Zionists, but what they had was an appeal to tradition and traditionalism that they knew how to translate that into a sense of shared values with the Mizrahim. The Revisionist appeal to restoring Israel’s ancient glory and the land promised to them by God resonated deeply with the Mizrahi community, as did the Revisionists portrayal of Labor as being made up of elite bureaucrats who care nothing for religious piety or the advancement of Israel to a position of strength among hostile neighbors. Labor saw the Mizrahim as a problem, while to the Revisionists, the Mizrahim were a solution.

Moreover, just as with poor whites in the American south who had more in common with poor blacks, the relationship between the Mizrahim and Arabs in Israel could be exploited. The Mizrahim may have been worse off than the Labor “elites” they came to hate, but at least they were better off than those terrible, Jew-hating Arabs. (Back in “Loki: or How Conservatism Becomes Fascism”, I put it this way: “Fascism at its heart is about the weak embracing a narrative to make them feel strong at someone else’s expense.” Indeed, this is the basis of the entire Revisionist project.)

There was one final ingredient to the coming ascendency of the Right in Israel, embodied by a Rabbi named Meir Kahane. Kahane believed in the fundamental supremacy of Jews over other races. In New York City in 1968, he’d founded a group called the Jewish Defense League that incited violence between Jews and blacks and Puerto Ricans and bombed Soviet missions and offices in protest of them not allowing Soviet Jews to immigrate to Israel. After several arrests in America for bomb-making and possession of firearms, Kahane immigrated to Israel in 1971. There he became the center of a new form of Revisionist Zionist Religionism. Among the positions he supported are the forceful removal of all Arabs from Israel (or their enslavement), the Occupied Territories, and the Kingdom of Jordan; prison for non-Jews who marry Jews; and the abolition of democracy in favor of theocracy—in other words, a kind of theocratic fascism. His Kach party was banned in Israel and designated a terrorist organization in the United States. However, Kahanists eventually formed the slightly more palatable Jewish Power party, which has grown into a major political force in Israel. Kahanism has inspired numerous acts of terrorism and its literally black-shirted militants currently roam the streets in lynch-mobs in Israel harassing mixed-ethnicity couples and attacking Palestinians.

In 1973, Arab states (primary Egypt and Syria) launched a surprise attack against Israel on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur. This was the first war that wasn’t a complete victory for Israel, a protracted conflict that resulted in a loss of both territory and lives (though only a small amount of territory compared to what they’d gained in ‘67), and lead to the resignation of Prime Minister Golda Meir. In 1975, 28 years after voting to create a Jewish state, the UN General Assembly endorsed a resolution saying Israel was “a racist regime in occupied Palestine” and a month later ordered the country to return all occupied Arab land without conditions.