In the 1990s, Doom and Myst fought a war for the soul of video games. Myst sold almost twice as many copies. Within ten years, the entire industry had remodeled itself around Doom.

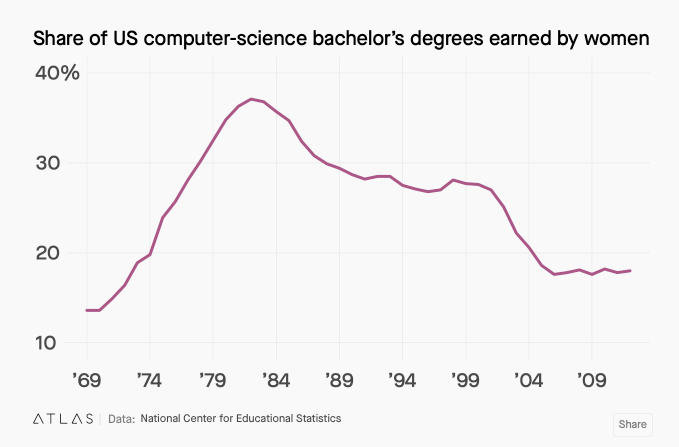

The seeds of the war had been sewn at the dawn of personal computing. As has been widely reported, computer programming was once the domain of women, positions descended from their earlier roles as human “computers”, solving mathematical problems for corporate and governmental work, labor considered rote and therefore “women’s work”.

As computer programming became more complicated, it gradually shifted to men, aided by personality tests used by employers that prioritized “stereotypically masculine traits and, increasingly, antisocialness”. Still, women in computing were common until the late 1970s when personal computers began to appear. These personal computers were marketed primarily towards boys, parents bought them for boys, and as a result computer science classes began to fill with those same boys who had grown up with the machines.

Marketing towards boys accelerated following the video game console crash of 1983. Then-dominant Atari had flooded the market with cheap and poorly produced games and the result was a loss in consumer confidence paired with the idea that the new multi-purpose personal computers had made dedicated consoles obsolete. And so it was when, in 1985, the Japanese company Nintendo decided to bring their new Entertainment System to the North American market, they packaged it with a little toy robot that would follow the player character around on the screen, so that it could be marketed not as a game console at all but as a toy. The console migrated out of the electronics shops and into toy stores.

As anyone who’s entered a toy store knows, the toy market is starkly gendered, with girl products in their rows of bright pink cordoned off from that of boys. Nintendo’s research said that boys played more games than girls, and so (as had happened with personal computers) they marketed their products exclusively to boys, creating a feedback loop attracted more boys while excluding girls. It wasn’t that girls couldn’t enjoy these games, it was that the company told both kids and their parents that this was a boys toy for boys.

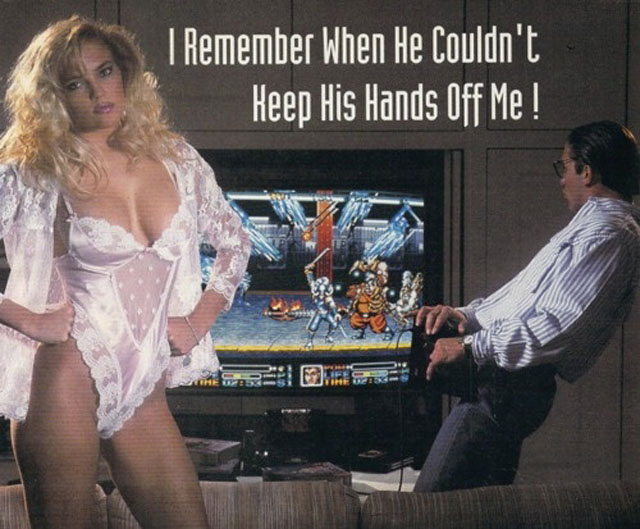

By 1989, when the Sega Genesis launched in North America, boys who had grown up on the Nintendo were now hitting puberty. Sega marketed their product as the cool game system, not like that childish Super Nintendo. The Genesis wasn’t just for boys, it was for the kind of boys who didn’t like icky girl things or little kids things or boring things. “Alpha” boys. Their mascot, Sonic the Hedgehog, perhaps tried a bit too hard to seem cool while embodying the fast action ethos of the company, but all the ads and marketing would prime the pump for what was to come. Marketing to boys became marketing to pubescent boys became marketing to stereotypes of pubescent boys, to make things fast and loud and free of thoughtfulness. Masculinity turned to toxic masculinity quick, and by the 90s all the game systems were flooded with ads that played up stereotypes and lurid pandering to the hilt. A Sega ad advertised a beautiful naked woman you wouldn’t notice underneath all these game screenshots. In a NeoGeo ad, a model in lingerie pouts at the camera while her boyfriend plays video games in the background with the text “I remember when he couldn’t keep his hands off of me!” A particularly infamous Sega ad showed a hand on a joystick reading “The more you play with it, the harder it gets!”. In 1998, there was even a Playstation TV ad in which a character is shown having to choose between playing manly games or being “totally whipped” by his girlfriend. (Discovered via an excellent article about sexist video game ads on Slate.)

In 1992 the Genesis gained two titles that would make it infamous and marked the natural result of the prurient bro-boy marketing strategy: Mortal Kombat and Night Trap. Originally in the arcades, Mortal Kombat was a fighting game whose characters literally pulled skeletons out of bodies amid geysers of blood. Night Trap involved the player watching ‘live surveillance’ of a family home where five teenage girls disappeared. While tame by today’s standards, the game’s focus on watching young women in scanty outfits get assaulted by vampires became caught up in one of the periodic video game moral panics and led to Senate hearings.

While console games fled fast into a single, boy-focused marketing segment, computer games had followed a different tack. Unlike consoles, basically anyone with a computer could make software that ran on these machines, and so a much wider variety of content appeared on them, including adventure games.

Adventure games had begun as text-only programs, where the player would get a description of a room or environment and then type a command of what they wanted their character to do. Quickly, graphics were added to these games, until companies like Sierra and LucasArts were turning out what became known as “point-and-click” adventures, where a character walked across a screen and the user would click on the objects or people they wanted to interact with. In this way, the player could explore a world, solve puzzles, and take part in an unfolding narrative.

While these games (like all computer games) were played predominantly by boys, the creators often pitched them towards a much wider audience and dreamed of a future where the computer game would stand beside mediums like film and television, enjoyed by people of all genders and age groups. With the dawn of the CD-ROM drive and the massive amounts of data it could store (many times that of the default storage medium of the time, the floppy disk), the imaginations of many game developers turned to so-called “interactive movies” using live action actors. As Sierra CEO Ken Williams put it, “I always thought the future of storytelling was on the computer. I predicted that computer games would be bigger than films, and still believe there is huge potential with story-telling games – if done correctly. Watching a story from the inside is more exciting than from the outside.”

But the true future of gaming would come not from the big name companies dreaming of celebrity castings, but from a rag tag group of men in their 20s operating out of a rundown riverfront house in Shreveport, Louisiana who came to call themselves iD Software. Their first game became a huge hit in the small Shareware scene of indie games at the time, a platformer in the Mario Bros. model, unflaggingly wholesome in both name and content: Commander Keen (1990-1991). (Shareware was a model in which software was distributed in part or in whole for free with the user paying for the rest of the program, or documentation, support, or simply to support the game makers. The tradition lives on in software trial periods, Patreon-funded developers, and so on.)

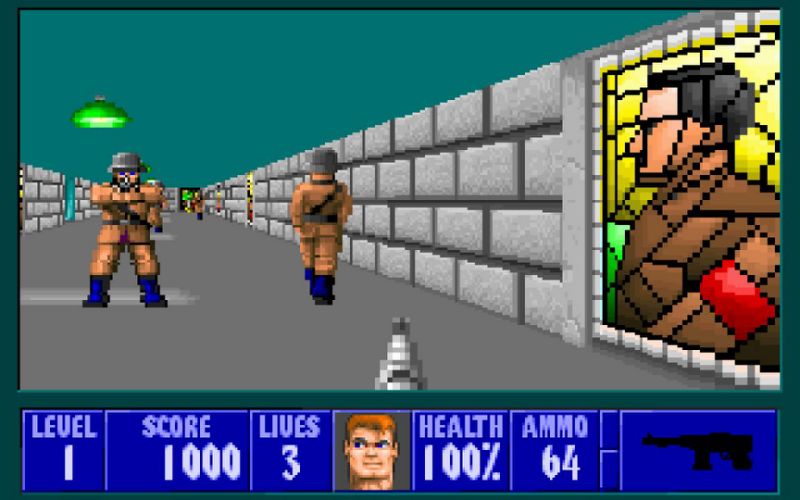

For their next game, they aimed for something more ambitious, and much more graphically violent. Deciding to make a shooter, they chose a homage to one of the original of the breed, Castle Wolfenstein (1981). Instead of the top-down view of the original game, or the side-view of a platformer, iD would place you inside the head of the protagonist, looking out on a 3D world. And the game would strip out everything but the barest essentials: here are Nazis, shoot them before they shoot you.

And thus was born the genre-defining Wolfenstein 3D (1992), which took off like a rocket, becoming probably the best-selling shareware game to that point, and getting reviews in mainstream publications that other shareware titles had only dreamed about.

Two months later, a long-anticipated A-List game came out with a similar 3D, first-person perspective—Ultima Underworld. And while the first person play was far more well-realized in this game (for example, you could move up and down, which you couldn’t in Wolfenstein 3D), as an RPG game the gameplay was far more cerebral, with puzzles, clues, maps, and skill leveling. There was a plot. Ultima Underworld was a successful game, but Wolfenstein, a game which had taken far less time and effort to make, ran absolute rings around it and became the game of 1992.

For their follow-up, iD improved the 3D engine to match Ultima Underworld, allowing true three dimensional views and movement and multi-level environments. They created a much wider variety of weapons, and instead of Nazis, the player would face all manner of creatively imagined demons and monsters. There would even be a handful of minor puzzles, places where the user had to, for example, push a button to open a door in another location. They would make the game that would lift them once and for all out of the indie, shareware world and into the stratosphere of the top mainstream game companies, creating a franchise that would last for decades. Doom.

Meanwhile, back in 1988, two brothers operating out of their parents’ basement in Spokane, Washington, were inspired by the new graphical development tool Hypercard (1987) for the Macintosh. With it, they created three children’s games focused less on achievable goals and more on simply exploring worlds, and founded the company Cyan, Inc. to sell them. By 1990, they decided to make a game for adults using the same system called Myst. Much as iD had stripped the action game down to its barest essentials, Cyan stripped down the point-and-click adventure game. Instead of a player-character walking around the screen, their game placed you inside the head of the protagonist, looking out on a 3D world. While this game would have bits of live-action video, the bulk of time would be spent exploring, finding puzzles, solving them, and unraveling the mysteries of the backstory and characters.

As first-person, 3D games Myst and Doom are actually quite similar. The primary difference between the two is philosophical.

In Myst, your character fell through a book into a world of fantasy. In Doom, your character was sent to a space station to put down out monsters. Gameplay in Myst involved exploration, unraveling a mystery, and solving puzzles. Gameplay in Doom involved shooting demons. Myst required a CD drive and the latest in SVGA graphics. Doom fit on a few floppies and ran on common VGA graphics. Myst had been released first on the rarefied Macintosh. Doom had been released first on ubiquitous MS-DOS machines. Myst was the game you bought to show off your new machine. Doom was the game you played on whatever you had. Myst appealed to a broad demographic, and actually, finally, had more female players than male. Doom was marketed to the same core demographic of pubescent boys who’d eaten up Mortal Kombat. Myst was beautiful. Doom was cool.

To be clear: it’s not that girls and women can’t enjoy shooting games. It’s that they’re not who these games were marketed to, targeted at, or who parents would think to give them to in our gender normative culture. Stripped down shooters like Wolfenstein 3D and Doom left in only mindless violence, which our culture associates primarily with masculinity.

Like Wolfenstein, Myst ascended from its humble origins to outsell the biggest, most expensive games on the market. It would have been the game of 1993, except of course that year also saw the release of Doom.

The sales numbers for these two games exponentially dwarfed most of their competitors. In a world where selling a few hundred thousand copies was considered a major hit, Doom moved over three million units, and Myst more than six million, and in doing so these games ushered in the era of the PC game blockbuster. And while it is true that Myst sold nearly twice as many copies as Doom, that statistic doesn’t tell the whole story. Like Commander Keen, Doom was distributed as shareware, which meant that the first few levels of the game could be freely copied and passed around. And those free levels traveled far and wide, making it onto store shelves in shareware compilations, as free giveaways with magazines, copied from person to person on floppies and CDs, and showing up on the dial-up bulletin boards, Gopher sites, newsgroups, and the primitive websites of the period. And so, while fewer people paid for Doom (and to be clear, many, many people still paid for Doom), an order of magnitude more people played Doom.

The end result of all this would take years to become clear. Companies fell over themselves to duplicate these games, in hopes of duplicating their sales. Doom-style games like Doom II (1994), (the aggressively sexist) Duke Nukem 3D (1996), and Unreal (1998) continued to sell like gangbusters. Meanwhile, Myst-style games like Zork Nemesis (1996), Lighthouse: The Dark Being (1996), and Obsidian (1997) were commercial disappointments. (Though Riven: the Sequel to Myst (1997) was successful, selling 4.5 million units.) And with them the point-and-click adventure fell out of fashion along with the dream of the “interactive movie” for the whole family. More and more games began to look like Doom. Other types of game play and game-player were pushed to the cultural periphery. The war had ended and Myst lay in a pool of blood and nostalgia.

So what happened? Why did the children of one blockbuster succeed while those of the the other failed?

People bought Myst for its beautiful graphics and intriguing story, and learning to play was as easy as clicking on things. However, the difficulty curve on the puzzles was sharp. The creators of Myst would later remark that most people probably didn’t make it off the first island/time period of the game (out of five). (I should also mention here 7th Guest (1993), another puzzle-based, point-and-click adventure game that sold well in part by showing off the potential of people’s computer systems, released in the shadow of Myst and benefitting from its favorable early reception.)

But the failings of Myst as a game (even if it turned people off of similar games) does not alone explain how the once booming adventure genre fell into decline, and why companies like Sierra and LucasArts largely stopped producing them, especially since Myst’s own sequel was a success. People sometimes blame ‘moon logic’ for the fall of adventure games, the tendency in them to have puzzles that were ill-thought-out or illogical. But LucasArts games were known for being largely absent of such issues and their games got rave reviews, so that explanation alone doesn’t cut it. (Though Jimmy Maher of the Digital Antiquarian opines that the LucasArts games actually did suffer in quality following 1993.)

As we saw earlier, after the rise of Nintendo, video game marketing focused almost exclusively on boys, turning gradually more stereotypical and toxic. The 90s were a decade that saw massive growth in PC home ownership from 20% of American households at the beginning of the decade to 50% by its end. Further, as home consoles and PC ownership rose, arcades—once the primary way kids played video games—declined. And so as the boys who had been marketed to in the 80s and early 90s grew up into teenagers, they became the dominate block of what came to be known as Gamers. And game companies under the capitalist impulse towards massive growth didn’t want to chase moderate success, they wanted the blockbusters they now knew were possible. Even LucasArts decline in quality can probably be attributed to the companies renewed focus on action-oriented Star Wars games. It wasn’t so much that the adventure game audience left as game makers left them.

And yet, what the similarities between Doom and Myst show is that there’s nothing about the first-person, 3D game that inherently means the primary activity must be violent. That’s a choice, and it’s a choice that game makers keep making even when trying ostensibly to make their games more narratively rich, thoughtful, and meaningful. Games like Half-Life (1998) would successfully mix the first person shooter with elements of adventure games, developing stories and characters and puzzles to be solved, demonstrating that there was still an audience for this type of thing, and future games would follow suit, absorbing, for example the dialogue tree method of interacting with characters. And yet because the core mechanic hasn’t changed, there are a huge number of people who will never discover the nuances of Bioshock (2007) or Mass Effect (2007), et al, because they have no interest in a game where you have to shoot people over and over to make the story go.

Of course, adventure games never completely died, and the rise of the internet, smartphones, and tablets have proved a fertile ground for new indies and revivals of classics. There’s even a much-touted VR adaptation of Myst on the horizon. But these are all on the fringes of what has become “gaming culture”, or, like casual games (think Candy Crush (2012) or Angry Birds (2014)), an ignored or ridiculed thing that is not part of that culture at all. Today, excluding sports games, almost any list of the most popular games is dominated almost exclusively by action games in the Doom mold. Myst might have been the last time (maybe the only time) a top-selling game of this class had more female players than male ones. Game companies essentially stopped trying to market to them at all.

Again, it’s not that girls can’t enjoy such games, it’s that they’re not the target audience of the game-makers. And it’s not that games like Doom are bad per se. The problem is with the methodology of slicing off a demographic, targeting to it relentlessly, encouraging people to associate brands with their self-identity, making what they sell not just a product but a lifestyle. It’s with aggressively crafting and marketing that brand through toxic masculinity because it sells, without any regard for the repercussions. And the result is what’s become “Gamer culture”. And when people have tried to point out that maybe some of this stuff is sexist, retrograde, or tasteless they’ve been shouted down, demonized, and literally terrorized, and from this toxified loam rose GamerGate.

GamerGate has been written about elsewhere at length better than I could hope to, but in short what began as a jilted ex trying to slut-shame an indie game maker by pointing out that that she’d slept with a gaming journalist ballooned into a campaign of harassment and persecution against women in gaming in general and women who pointed out sexism and lack of diversity in games in particular. And this provided a template for harassment campaigns against supposed “social justice warriors”, a festering cesspool of white, male grievance from which shooting rampages happen. (As Slate pointed out, the actual connection between real shootings and video games is not violent games causing violent behavior directly as hang-wringing moralists and bad-faith gun activists have claimed, but rather the culture that has risen up around them.)

There was a moment in the 90s where this seemed like it wasn’t going to come to pass, where the popularity of Myst and the drive towards narrative games aimed at a wide audience might have created a gaming culture more like the general culture, an audience as wide and vast as that of other mass media. But a capitalist would argue that this result was simply the law of the marketplace: First Person Shooter games sold better and so their rise was inevitable. But choices had been made all along, beginning with the marketing computers primarily to boys at the dawn of the PC, which meant that even when Myst was popular with women and wider audiences in general, the culture didn’t exist for them to become a part of, while Doom found a massive audience primed and waiting. The war had never been a fair fight, the entire playing field tilted in favor of Doom and its successors.

Of course, video games are now more popular among ever wider audiences, and adventure games are having a bit of a revival. Maybe, while everyone’s distracted by ‘esports’ and streaming celebrities, a new kind of gaming culture is just beginning to emerge.

Special call out to Jimmy Maher at the Digital Antiquarian (https://filfre.net) whose work covering early video games I drew on extensively.

If you’d like these articles early or to get exclusive writer’s notes on each one, consider donating as little as $1 a post on my Patreon

Pingback: Frustrations with Myst - CVGS