Podcast Version • Get This in Your Inbox

Content Warning: Suicide, sexual abuse, rape, grooming, and extreme sexism.

The 1970s were a time of death and rebirth for the comic book industry. Traditionally, comics had been sold at newsstands, but the newsstand market was drying up and people predicted the whole industry’s demise. However, inspired by the hippy head-shop scene where underground, independent comics had been sold since the 60s, the first dedicated comic book stores started opening and with them the first dedicated distributors. While this development helped close off comics from the general reader and gear it towards the enthusiast crowd who came to dominate its fandom, the newly abundant shelf space in need of filling became amenable to small publishers and self-publishers in a way the medium had never seen before.

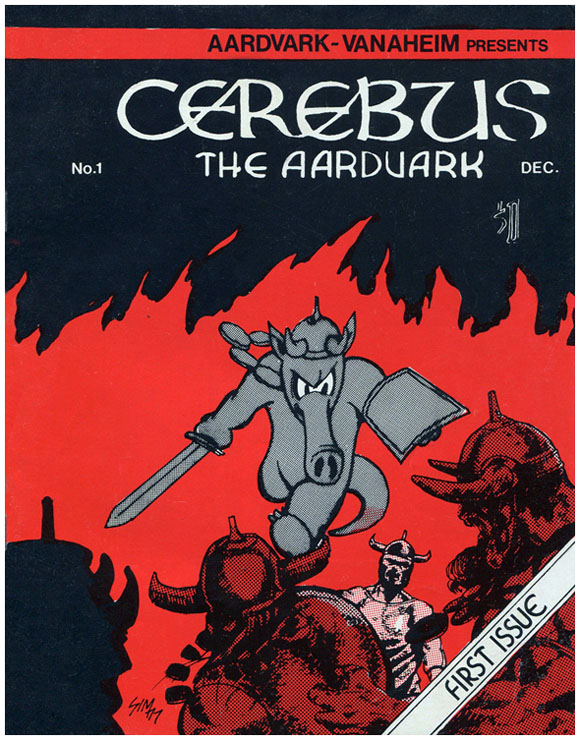

It was in this environment, in 1977, that a 21-year-old Canadian artist/writer named Dave Sim produced the first issue of Cerebus the Aardvark, a parodic mash-up of two popular comics of the era, Conan the Barbarian (based on the pulp stories from the 1930s), and funny animal in the modern world comic Howard the Duck, and aimed squarely at the heart of the burgeoning geek audience. One of the early successes of comics self-publishing, Sim would continue producing his comic almost every month for the next 30 years. Over those years, Sim became an exemplar of the kind of idiosyncratic, iconic artist who did exactly what they wanted however they wanted, and in so doing would push medium in strange and exciting directions.

And Cerebus might be primarily known in these terms, a cult phenomenon from before the dawn of the web that paved the way for utterly singular and independent visions in narrative media like, say, Homestuck. Except that if you’ve heard of Dave Sim, one thing about him overshadows everything else: Dave Sim is a misogynist.

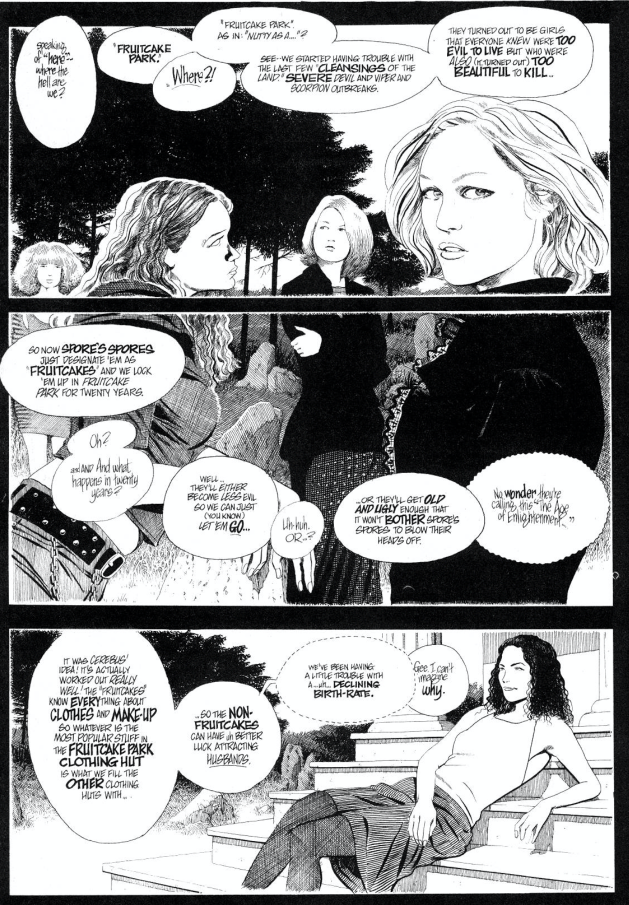

Now, Sim himself will talk at length about how he’s not a misogynist, he’s simply “anti-feminist”. And the truth is, he’s not a misogynist the way your uncle who watched Fox News is, or in the way we see misogyny in the world around us all the time. No, much as his comic book is bigger and weirder than anything else, his misogyny is bigger and weirder than anyone else’s. Everyone talks about the big break in the middle of the Mother’s and Daughters storyline where a barely fictionalized version of Sim cuts in to explain how women are psychic vampires, voids that feed off of male light; where he writes things like “If you look at her and see anything besides emptiness, fear and emotional hunger, you are looking at the parts of yourself which have been consumed to that point.” That’s when most sane people threw the comic away and went about their business. But that was barely half-way through the series’ run. Before it’s over, Cerebus the Aardvark dresses up like the superhero Spawn but with a Charlie Brown shirt and stilts and a scorpion stinger tail to pose as some kind of demon and lead a rebellion in which women who are too uppity get executed unless they’re too pretty to execute, in which case they’re put in a kind of garden preserve so they can be ogled until they’re old enough that they’re not pretty anymore and can safely be executed.

That’s the sort of misogynist Dave Sim is.

And yet–and this is true–Sim forces anyone who wants to so much as talk to him sign a document affirming that they don’t think he’s a misogynist. He doesn’t hate women, he wants you to know. He just thinks they’re incapable of rational thought and should be stripped of all rights, completely subservient to men. What’s misogynist about that?

More recently, much has been made of Sim apparently grooming a 14-year-old fan for sex, though he claims this is okay because he didn’t actually have sex with her until she was 21, which is kind of the definition of grooming. (Dave Sim is not a good person.)

If you know anything else about Sim, you probably know that he’s mentally ill. He was diagnosed with “borderline schizophrenia” and does not treat his condition, and it’s very easy to read through the Cerebus volumes as a document of his deteriorating mental condition. You see, there was a point in the mid-80s, before Mothers and Daughters and everything after, when he self-identified as a liberal and Cerebus was hailed as a comic with well-rounded female characters, celebrated by feminists because its women characters had complexity and depth so often lacking from other comics of the period. And what a strangely magnificent and magnificently strange comic it was at its peak of popularity.

According to Sim’s self-mythology, in 1979 he discovered LSD and, enamored of its effects, ate it basically continually for a week and a half. This resulted in a nervous breakdown during which his wife had him committed to a mental hospital. There he received both his diagnosis and a creative epiphany about his future: he would transform his little, humorous aardvark comic into a vehicle to tell the story of his character’s whole adult life until death, an epic fantasy narrative that would take 300 monthly issues. The fact that he actually went ahead and did what he set out to do as a drug-addled 23-year-old is nothing short of miraculous, a testament to sheer will.

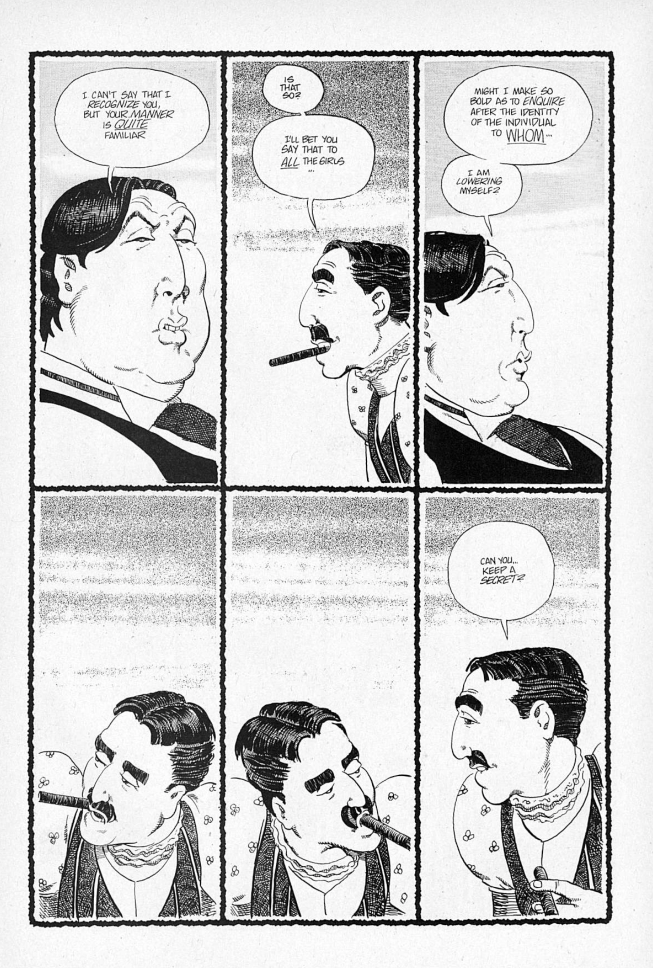

Cerebus had always been a vehicle for parodic characters, beginning with ones related to his fantasy milieu like Conan flame Red Sonja or Michael Moorcock’s Elric the Albino (who becomes “Elrod of Melvinbone” and speaks and acts like Foghorn Leghorn). The comic takes its first strides into brilliance with the introduction of Lord Julius, who is simply Groucho Marx as the leader a medieval city state. The move not only gives Sim an easy way into political satire—as demonstrated by Duck Soup (1933), making the comically venal and fast-talking Groucho into a head of state is inherently satirical. (Sim also has a knack for comic pastiche, nailing Marx’s vaudevillian sense of humor as he later would that of comedians from Rodney Dangerfield to the Three Stooges.) Further, it creates an avenue where Sim can introduce other real people into the narrative to increasingly post-modern effect as Chico Marx, Mick Jagger and Keith (or “Keef”) Richards, and even obscure historical figures like Adam Weishaupt (the founder of the Order of the Illuminati) all become players on the political stage as Cerebus is manipulated into becoming the prime minister of a city-state himself and ultimately pope. Cerebus also makes an excellent foil for all the pretentiously self-important and manipulative people around him by remaining a stubborn and single-minded simplification of the already simple character of Conan. (His first command when becoming pope is that everyone, everywhere must bring him all their gold. Cerebus is not a good person.) Throughout all this, Sim’s art improves from its modest beginnings to masterful levels, and he brings in a background artist named Gerhard who gives his world palpable depth and texture.

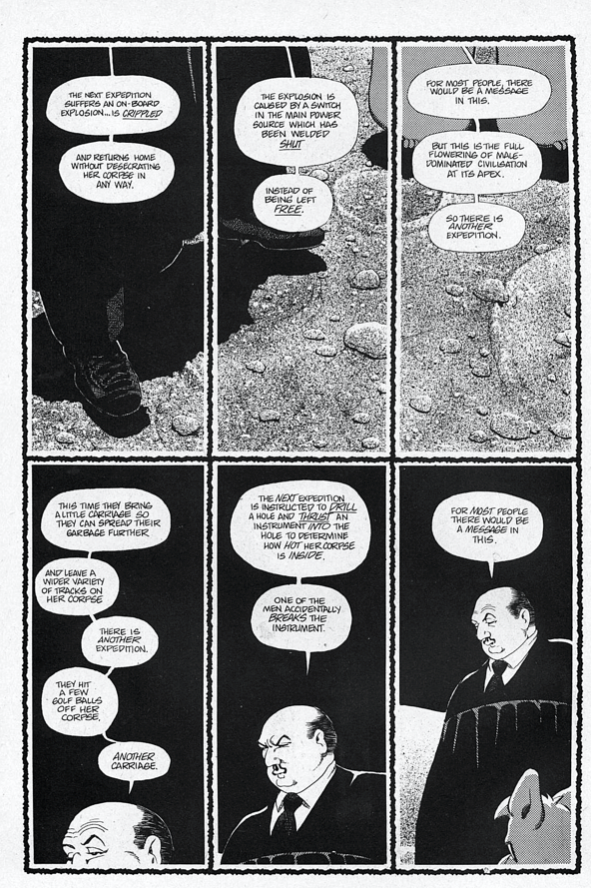

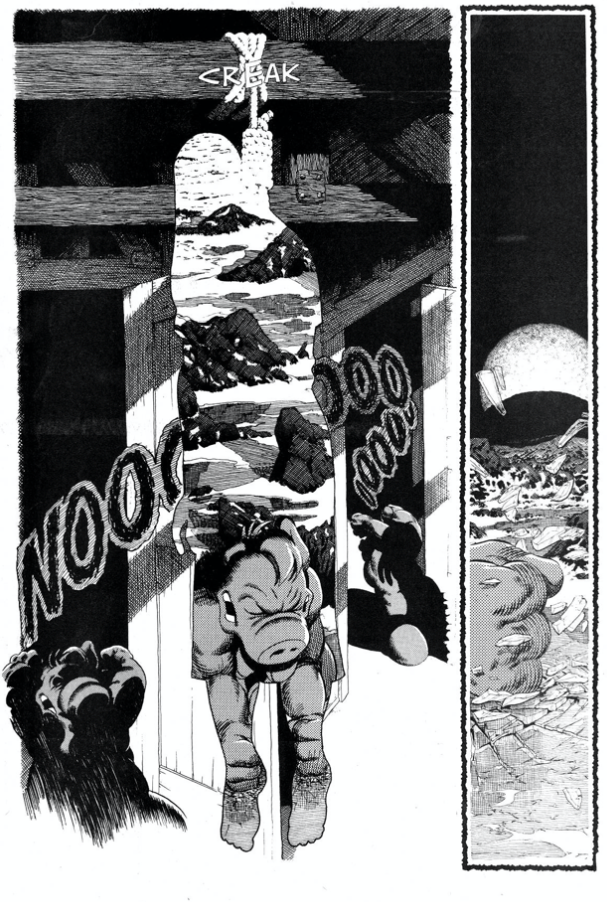

The pope storyline climaxes in the surreal, as President Weishaupt and Cerebus battle for an orb that will create a spinning tower who’s surface is carved entirely out of skulls. Upon winning the battle, Cerebus walks up the side of the tower to the moon. There he meets the Judge, a parody of Marvel Comics’ omniscient character The Watcher who for some reason looks like an actor who played a judge in the obscure film Little Murders (1971). The Judge tells Cerebus a story about the beginning of the time, where a male void rapes and shatters a female light, giving birth to the universe.

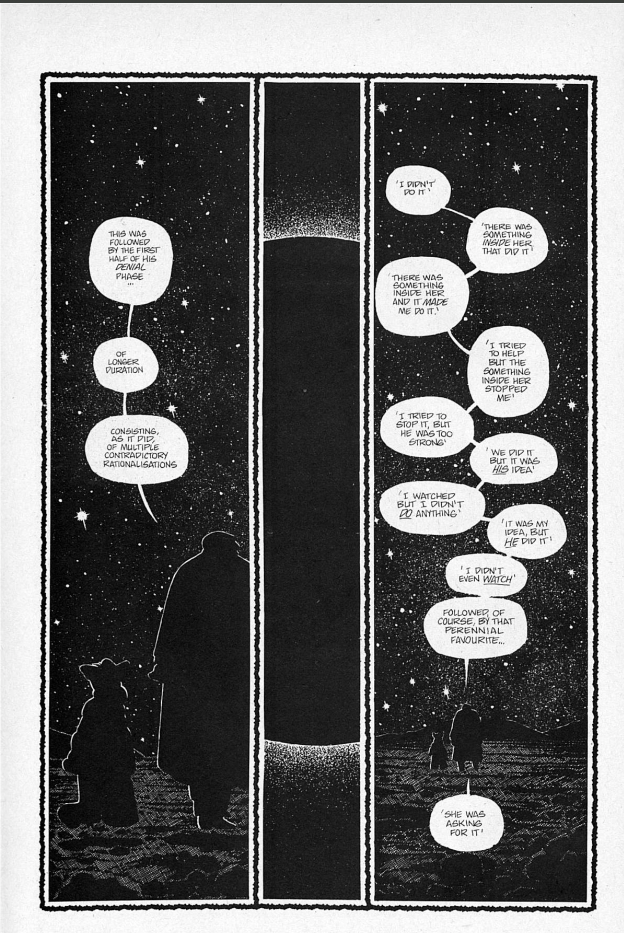

Wait wait, you’re thinking, wasn’t Sim’s whole game about female void and male light? Why would he make a metaphor that appears to condemn toxic masculinity and sexual abuse? (And he makes this explicit, saying that men break women and tell them they were ‘asking for it’.)

Sim himself later calls this the “ultra-female” reading, setting up the revelations that would come later after the judge is revealed to have been “lying”. At any rate, it shows how the deep the gender issue went in his personal cosmology, serving as the climax of the story.

When Cerebus is sent back to Earth, we discover that in the chaos and war leading up to and following his ascent, his region of the world had been conquered by the Cirinists, a fascistic matriarchal cult. Still, it’s not yet clear that something is terribly wrong with Sim and the story he’s telling; other than all being women, the Cirinists more closely resemble the right wing, with the women all wearing masks a la conservative Islam and with social order and activity kept under tight control. I mean, one of the Cirinists is Margaret Thatcher, for Pete’s sake (and she’s delightfully creepy). We don’t yet know that the Cirinists are Sim’s idea of feminists, of leftists, of what his incoherent fever dreams imagine as liberal’s endgame. That they’re just “feminazis”.

Perhaps this is somewhat unfair; there’s a second group of feminists called the Kevillists who oppose the Cirinists and want freedom and equality in a way more recognizable to the modern reader. (These are the “daughters” who oppose the “mother” Cirinists that value motherhood above all else.) Their leader is a woman named Astoria, whose schemes made Cerebus prime minister, and who comes off as a fascinating character torn between ends and means. One of the earliest Cerebus scenes that people took issue with was after Cerebus becomes pope he has Astoria imprisoned and rapes her. (Cerebus is a piece of shit).

The impression of this scene is bifurcated by what comes later. At the time it seemed Cerebus’ rape was, like his demand for gold, another example of how everyone thought he could be manipulated because of his simple-minded and unbridled self-interest, only to discover that giving power to a monster benefits no one. (One thinks of certain contemporary political figures who also seem like a cartoon in a world of humans.) It’s also a canny send-up of the whole concept of the “barbarian hero”, showing that someone who behaved like Conan would be less of a anti-hero and more of a straight villain.

But of course this interpretation of Astoria and the Kevillists is later contradicted. During Mothers and Daughters, Sim even has Astoria claim she manipulated Cerebus into raping her in hopes of having an aardvark child, who in this world are figures with great destinies. The rape is, in other words, the woman’s fault. The Kevillists are just amorally self-interested users of men, no better than Cerebus himself.

Following the big pope/moon story, Cerebus’ adventures become much more small-scaled and introspective. The next storyline is about Cerebus hiding out with his love interest Jaka, who’s married another man, and it’s mostly just this quiet unrequited love story, with Oscar Wilde poking about and delivering one-liners. (The scene where Wilde meets Groucho Marx is one of the all-time classics of the series.)

The story climaxes when the Cirinists arrest Jaka for illegally exotic dancing, summarily executing her incel-like employer. There’s an emotional scene where the Cirinists reveal to her husband that she aborted the child he desperately wanted, and he hits her and they punish him for it. Sim calls it a story without a villain, and despite a cringe-worthy sequence where Jaka is interrogated by Thatcher and seems to have no sense that her dancing has any sexual component at all, the portrait of her has depth and nuance, with a series of flashbacks to her childhood fleshing her out as a character. The ending came off as much more thorny before you knew Dave Sim’s feelings about abortion.

Amid all of this, the storytelling techniques Sim deploys, his layouts and pacing, the expressiveness of his figures, even his lettering are so compelling and original that it’s hard not to get swept away; it’s with Jaka’s Story, I think, that it becomes clear that Sim is one of the most skilled comics artists working. Also during this time, Sim championed self-publishing in comics, helping to create the “Creator’s Bill of Rights” for comic book artists and giving boosts to lots of up-and-comers, including the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles when that was still a self-published, black-and-white comic no one had heard of, and Jeff Smith’s Bone.

After this storyline we get, unexpectedly, an elaborate adaptation of the last years of the life of Oscar Wilde, making extensive and compelling use of extracts from his letters and with no hand-wringing at all about the man’s homosexuality. (In this world Wilde was punished by the Cirinists for a lack of “artistic license” rather than for sodomy by the courts of Victorian England.) In the previous storyline, Wilde had even stood up to Jaka’s employer and his homophobic insults. This is fascinating since later Sim becomes ardent in decrying the homosexualist agenda, and has said that he thinks homosexuality “belongs at the margins of society and behind closed doors.” But clearly he loves Wilde and is rapt by the same dramatic fall which has long since made him the gay martyr.

After this, it’s the four-book arc of Mothers and Daughters, whose lose plot climaxes when Cerebus finally confronts Cirin, leader of the Cirinists and a fellow aardvark, and the whole thing is entirely overshadowed by the textual insertions where Sim lectures us about the world. He describes a new, inverted version of the Creation, with male light impregnating the female void and builds to the famous issue 186, where all pretenses are ripped away. “It’s not your body they’re after but your soul,” Sim helpfully tells us when explaining how women siphon the power of men, and how they must be held tightly in check. Women have no business working or voting or doing much of anything besides rearing children and having sex. They’re not really people in the same way men are, they can’t reason, they can’t be trusted.

And we’re now confronted with a floodgates-open display of his mental illness. One of his many claims about women, for example, is that they can literally read minds, and the names of the sub-volumes of Mothers and Daughters spells this out (“Women Reads Minds, Guys”). (Technically the first volume of Mothers and Daughters is Flight and Guys is an epilogue, but whatever.) Everything in the universe it seems, even abstract concepts like Birth and Death, are gendered in Sim’s mind and this gendering reveals secret truths about the workings of the universe. (In later issues, Sim even genders the laws of physics, positing, for example, that hydrogen is female (because it desires to “merge”) while helium is male (because it doesn’t).)

It’d be nice to attribute his turn to misogyny entirely to this psychotic break, to say he just went crazy. Did he really write the Judge’s version of creation just to knock it down later? Did he really think of Astoria and Jaka as psychic vampires incapable of reason even has he wrote them so sympathetically? It’s impossible to know for sure, but the Cirinists were introduced as early as issue 20, when Sim still described himself as a politically liberal. If Sim himself is to be believed, he felt this way about women for a very long time. In any case, his mental illness appears to have taken his misogyny and ballooned it to monstrous proportions.

Reading about Sim online, I get a little frustrated when I see otherwise intelligent people claim that Sim isn’t really mentally ill at all, or that his mental condition has no bearing on his work, even while they also tell you that Cerebus can be properly read as a document of the inside of the man’s head. Someone who thinks that women are telepathic, that they syphon all rational ability from men and are incapable of differentiating between [humans] and animals is not someone in touch with consensus reality, and the only way to make that claim is to avoid describing his beliefs in depth.

And Sim’s mental illness has had tragic consequences for his own life; he’s alienated almost everyone he knows personally including Gerhard, and become a virtual hermit and self-described “voluntarily celibate” (though he sometimes rewards himself with trips to a local dance club so he can ogle young women).

On the subject of his own diagnosis, Sim has written, “the definition of schizophrenia—the inability to perceive the difference between reality and fantasy—is, to me, self-evidently ludicrous because it presupposes that there is universally agreed upon perception of what reality is”. Which I suppose is at least how Sim can still think of himself as sane, by denying any such thing as sanity exists in the first place.

At the climax of Mothers and Daughters, Cerebus is spun off into space again on a floating cube that brings him to Pluto where Dave Sim personally speaks to him as a voice in his head. Sim confirms something a character previously said, that Cerebus is in fact intersex, with both male and female sex organs, this assumably explaining his over-emotionality. He berates Cerebus for never learning his lesson, for still wanting to be with Jaka. Cerebus asks for Jaka to love him unconditionally, and Sim shows him several alternate futures where Cerebus is abusive, Cerebus is a cheat, where Jaka kills herself in remorse. (Did I mention that Cerebus is fucking awful?) Finally, he’s sent back to Earth.

Sim himself has said that the Cerebus narrative essentially ends with Mothers and Daughters, and everything after it is postscript. In the following books, the character is barely a lead, drinking in a bar for page after page before Jaka shows up again, and then they go off and there’s books where Earnest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald appear and Sim examines their lives in a way which doesn’t really directly connect to anything else in the series.

Jaka, the once great character, is here reduced to a shrill bimbo, and Cerebus ultimately rejects her when they travel to meet his parents only to find out they’ve died while he was away and this is somehow Jaka’s fault for being a distraction. (Notably, Dave Sim refuses to talk to his own parents.) He then leads a final revolution against the Cirinists which results in the Spawn-dressing and uppity women executions I described earlier.

After this, Woody Allen wanders in with the literal Torah (the first five books of the Bible). Sim, once an atheist, at some point had a complete religious conversion where he decided he was simultaneously a Christian AND a Jew AND a Muslim (but really a kind of syncretism of the three of his own devising). Allen and Cerebus spend several issues on an exegesis of the book of Genesis in which the details of Sim’s new beliefs are outlined. Genesis, when read correctly we find, secretly tells the story of a war between a male diety, God, and a female diety, YHWH (Yahweh in the Jewish tradition, though Sim refers to her derisively as “Yoowhoo”). Which is to say that his “light and void” idea of creation is not a metaphor, or an interpretation, or even a theory as we once might have thought, but the capital-T Truth found in holy scripture. (As pointed out by one of the excellent posts on the subject of Cerebus by Tegan O’Neil, it takes a certain chutzpa for someone to look at Genesis, the most read and reread book in the history of world, and decide he’s the only one that knows what’s really going on with it.)

In Sim’s belief system, we live in a kind of fallen world, an age of the Female Void. “We are already past the point of no return,” he wrote. He believes civilization’s been on a downward slope towards feminization since the death of the prophet Muhammed, and rejects basically all post-enlightenment philosophy as “bafflegab”. He does not have a cell phone or an email address (though he bought a computer some years ago which he says is specifically for Google Image Search). He claims artists who use computers in their work aren’t artists at all but “technicians”.

Cerebus came to its intended conclusion in 2004, with the lead character, as predicted by the Judge, dying alone, unmourned, and unloved when he trips, farts, falls and is sent to Hell. (Sim at least knows Cerebus is not a good person.)

In the following years, Sim released a few comics projects including Judenhass, a straightforward retelling of the story of the Holocaust which relies heavily on primary sources, and Glamourpuss, a parody of fashion magazines that also included a serialization of a history of the now unfashionable “fine line” comics art style which he practices. Because he stridently believes in creator ownership, he gave Gerhard half ownership of Cerebus, and has been progressively buying back those rights from him.

In February 2015, Dave Sim started suffering from an unknown condition causing tremors in his hands and hasn’t been able to draw since. He’s refused any modern medical treatment because he doesn’t “believe in medical science,” which also explains his lack of a diagnosis. He sees the condition as a divine test of some kind because “any other assumption… begs credulity.”

Since then he’s released a series called Cerebus in Hell, in which public domain art like that of Gustave Doré is collaged with old Cerebus artwork in order for Sim to continue expounding on his ideas about the world. Recently, he’s produced a free Coronavirus special packed full of flaccid jokes about how we’re all panicking over nothing.

Cerebus stands as curious thing. It’s an indelible part of comics history by one of its most skilled practitioners whose whiz-bang pyrotechnics of graphical storytelling–framing of pages, sequencing actions, establishing a mood, communicating emotion, are virtually unrivaled. It’s plot seems to meander off into whatever Sim happens to be thinking about at the time and has very little relation to classical notions of structure or character development, with long textual passages and virtuosic pastiches of the styles of other writers and various comedians. It is the singular and untrammeled vision of a creator, and in a world where every marginally notable piece of art is hailed as unique, it can truly be said that there is nothing even remotely like it. And it’s an example of how someone can make it completely on their own, earning a good living creating precisely the art they want unencumbered by interference from major corporations.

It’s also thousands of pages of unbridled hate speech.

And so it’s difficult to recommend reading Cerebus to anyone at all. Perhaps it will be a rich vein for academics of 20th century graphic storytelling and popular culture. And perhaps artists in the future will find ways to mine and remix its innovations. In this way, and despite itself, Cerebus may finally find its legacy.

Special thanks to the folks at the Eruditorum Press Discord for voting on what the next episode should be about.

If you enjoyed this, please consider telling folks about it. Word of mouth is how projects like this grow.

You can support this project for as little as $1 a month on Patreon, and get early previews of new episodes and exclusive writer’s notes.

Thanks to my Patrons: Nancy Rosen, Arthur Rosenfield, Ben Pence, JF Quackenbush, IndustrialRobot, and Not Invader Zim.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- A collection quotations of Dave Sim’s most misogynistic writing

- An account of Sim’s LSD epiphany at the unofficial Cerebus fanzine site

- Sim on his schizophrenia diagnosis

- Tegan O’Neil’s excellent posts on Cerebus have been a great resource for this piece, which are indexed here. The comment about Sim and his interpretation of Genesis is found in part 1 of her series.

- Sim on his injury and medical science

- The Cerebus in Hell Coronavirus special

5 comments on “Cerebus: Misogyny and Madness”