Audio Version | Get this in your Inbox

This piece spoils the entirety of the show Schitt’s Creek.

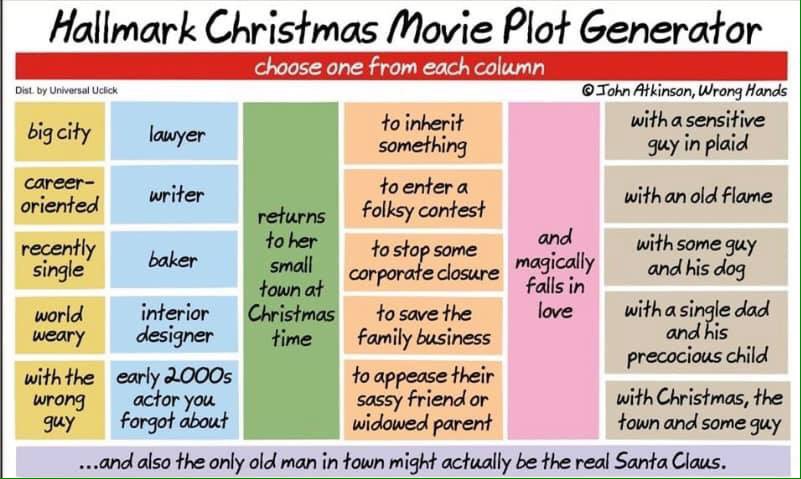

Around Christmas, there was a meme going around about Hallmark Christmas movies and how they all have about the same plot: a woman who’s prioritized her career in the big city returns to the small town she came from and resents only to fall in love and discover her old home is where her heart (and the meaning of Christmas) was all along.

This notion of small towns as homey paradises where people have a connection that can’t be found in the world of the big city is hardly new. It’s easy to think of idealized small towns in popular media, going at least as far back as shows like Leave It to Beaver (1957-1963), The Andy Griffith Show (1960-1968), and so on. Nor is the story of a big shot, big city type coming to the small town and falling for it anything new. Hell, even just looking at my teenage years I can think of examples off the top of my head, such as Doc Hollywood (1991), Groundhog Day (1993), and Northern Exposure (1990-1995). And all of these narratives happen in more or less the same sort of place, filled to the brim with goodhearted but quirky folks, always there when someone needs them, whose simple, wholesome lives leave them basically happy and satisfied in a way that contrasts with the unfulfilling ambition of the big city.

This fetishization of the small town might come as some surprise to those who like to imagine Hollywood (and by Hollywood here I’m referring to the entire pop media machinery) as populated by out-of-touch, big city elites who look down their noses at “flyover country”. But I think this speaks to a contradiction in the (particularly white) Coastal imagination about small towns in the middle of nowhere, which are at once dull backwaters best to escape from and places you could imagine fleeing to, free from the daily grind where housing is affordable, folks are neighborly, and one could find a sense of community.

TheAndy Griffith Show is an interesting case because of the way that folks on the right still like to bring it up as an example of the kind of values we supposedly need to get back to. {clip} Yet the actual values on display don’t really line up. Griffith’s Sheriff Taylor refused to wear a gun because he said “when a man carries a gun all the time, the respect he thinks he’s getting might actually be fear”. {clip} There was a running gag where his deputy, Barney Fife (Don Knotts) had a gun but had only been given a single bullet he never got to use. This was of course in stark contrast to the real life American South (the show takes place in North Carolina) at the time of airing, where protestors in the civil rights movement were being beaten and shot for the temerity of sitting at lunch counters, riding buses, and trying to vote. Ted Koppel did a whole piece on CBS Sunday Morning on how the right’s fetishization of Griffith’s Mayberry is a yearning for a past that never happened fueled by the same sort of people who believe the absurd claims of voter fraud in the 2020 election.

No, these small towns are by-and-large as much a fantasy as anything in Game of Thrones. And as the real-life small towns in North America have been hollowed out by outsourcing, conglomeration, and predatory capitalism, this Hollywood version has become ever more disconnected from that reality in a way that illustrates how we’re all blind to everything we’ve lost.

Which brings us, at last, to Schitt’s Creek.

Now, I want to say right off that I like Schitt’s Creek. As with The Trial of the Chicago 7, one can enjoy a piece of media while also finding fault with its ideological bearing or point-of-view (intentional or otherwise). Full of heart and generous sentiment, it’s a show about people finding reconnection, love, and community in a time of distress and loss. It’s hardly a surprise this warm blanket of a show became popular during the era of Trump and Pandemic. But the ways in which it’s a warm blanket perfectly encapsulate the lies we’ve been telling ourselves as a culture about the society we live in.

Ostensibly, you see, Schitt’s Creek is a show about poverty.

The show tells the story of the Rose family, whose patriarch Johnny (Eugene Levy) built a massive fortune off a VHS rental chain, only to find themselves destitute after their financial planner absconds with all their money. After their palatial, marble-fitted mansion is seized by a non-denominational “revenue authority”, they’re left to live in a motel in a small, rural town that Johnny once bought as a joke. (What it means in legal terms that they “own” the town is never really clear, and it doesn’t seem to grant them any particular property rights–they’re only allowed to stay in the motel at the sufferance of the mayor, the improbably named Roland Schitt (Chris Elliott).) Thus the premise is what happens when rich people find themselves utterly destitute, and the thrust of the show is about their quest for the means to get themselves back on their feet.

As a viewer, I thought I knew how this story was going to go, like any big-city-to-small-town Hallmark narrative. And this is how it seems to be going for much of its runtime. The Roses learn humility and heart from the local townspeople, discovering the hollowness of the life they used to live and the lack of real connection with the people they’d known. Again and again we’re shown members of the Rose family interacting with people they knew while they were rich, who are revealed to be selfish, venal, and inconsiderate, good time friends who disappear when they’re most needed. The implication is that wealth has a corrosive effect, that it makes you lose touch with your humanity and lose sight of what’s important in life. In the small town with salt-of-the-earth people, on the other hand, they discover who they really are.

But at the same time the Roses are steadily building back their finances, often through improbable good luck, and the show finally swerves completely from the typical narrative by having Johnny get venture funding for his new business and all but one member of the family leaving town in the last episode to go right back on the road to wealth. Which seems to contradict all the themes that had been established so far about wealth being soul-destroying and small town values being superior to those of the big city. It would be one thing if this was a straight-up subversion of the clichéd ending, if this somehow commented on the ways in which the Hallmark Christmas movie distorts reality. But nothing else about the show supports that reading; it just seems like after spending four years developing and growing as people, the Rose family simply decides that wealth and the big city aren’t so bad after all. The ending, in other words, is confused, and confused in a way that makes me think that the writers weren’t actually aware of the thematic implications of what they were doing.

But the clues that this might be the case were there all along. For a show about poverty, after all, Schitt’s Creek can never bear to show us what actual poverty looks like. There’s no opioid epidemic here. No Walmart destroying local businesses and paying poverty wages. Nobody blaming immigrants and liberals for their problems and spiraling into mires of insane conspiracy theories. The closest glimpse we get of small town financial struggle is an early episode focusing on the very real epidemic of Multilevel Marketing scams in small communities. The Rose family buys into an MLM and tries to sell the poor quality cosmetics they receive to the townspeople, only to discover they’ve all already bought into it themselves in years past. But there’s no sense here that the MLMs prey on small towns precisely because they tend to have so much desperate poverty, and there’s no sense of anyone being financially ruined by their involvement in them.Further, there’s no one finding refuge from their troubles in the Church, despite that institution being central to the cultural life of most North American small towns. There are no Bible thumpers here, none of the zealots who would occasionally corner me to talk about my immortal soul even when I lived in towns in Liberal states like Connecticut and Vermont. We don’t see pregnant teenagers and shotgun weddings because people don’t believe in using or distributing information about contraception and have made it nearly impossible to get abortions.

And we don’t see the worsening urban/rural divide that’s caused white, rural and suburban Americans to rail against the phantom of “Critical Race Theory” and bash immigrants, poisonous distractions that allow the politicians they support to continue executing the very lassez faire capitalism that’s destroying their communities.

Indeed, there’s no politics at all in Schitt’s Creek, despite one of the major characters being a professional politician and a plot line revolving around the mother Moira (Catherine O’Hara) running for and winning a seat on the town council. I counted two political jokes in the entire series: when the town community theatre is putting on a musical and there’s a joke about Cats being a more political show than Cabaret (a show about literal Nazis); and then when David Rose (Dan Levy) says he doesn’t like sports because ‘Given today’s political climate, we don’t need to divide ourselves any more’ (despite the fact that we never see any evidence of that division). And we see no intolerance, bigotry, or racism. The closest we get is a scene where David thinks his fiancé Patrick’s parents are upset to find out he’s gay, but are actually only upset because he didn’t tell them. “For a minute I thought this was gonna get very dark,” David says in relief. Fortunately for him, the show could never bear such darkness.

Of course, this is all what we’ve come to expect from the Hollywood version of small town America, a function of the show as a warm blanket. But the elisions becomes glaring in a show that’s premised on showing us the effects of poverty on a family. They’re noticeable.

Further, the show seems to have no idea how the working class lives or works. Almost no one in town, for example, is involved in wage labor. Everyone is either a small business owner or becomes a small business owner by the end of the show, often through luck. Motel manager Stevie, for example, who appears to be the only employee of the motel in which the Roses reside, unexpectedly inherits the whole business when it’s revealed that it was owned by an unseen aunt who dies and leaves it to her. The son David Rose gets a job as a salesperson in a clothing store when unexpectedly his employer is offered money for the name of the store by a foreign business with the same name looking to expand. David and his sister Alexis (Annie Murphy) help her negotiate for more and are rewarded with a large check, which David uses to start a local retail store. Alexis (after temporarily working reception in her boyfriend’s veterinarian business, a position, it’s made clear, she’s not remotely qualified for) decides to start a public relations company, is hired by her mother to help promote her own resurgent acting career, and unexpectedly causes a fiasco at a press conference that goes viral and transforms her ‘company’ from a notional idea to an in-demand concern. Stevie practically begs Johnny Rose to help her run the motel because she has no business experience, which he then works to expand into a chain that ultimately allows the family to leave town. Even the mayor Roland becomes co-owner of the motel business by (recklessly) mortgaging his house when they need extra capital.

Meanwhile, Ted is a veterinarian with his own practice (though, yes, he later gives it up for a dream job doing research on Galapagos). Ronnie is a contractor. Bob owns a car repair business. Ray runs a one-man real estate agency among other businesses. Even Moira’s acting career is a kind of small business in the way all independent artists are, always needing to line up the next gig. In terms of what’s depicted here, wage labor is seen as at worst a temporary inconvenience to be overcome when you finally start your own business, which hopefully will fall in your lap when you’re ready for it.

And this despite the fact that those who do work wage labor jobs before their entrepreneurial ascension, Alexis, David, Stevie, and Twyla, are all shown to be pretty content in their jobs while they have them.

But it’s Twyla (Sarah Levy), the waitress at the local diner, who’s story is the most glaring example of the problem here, the way in which the show seems completely oblivious to the problems of working wage labor.

In the second-to-last episode, Alexis Rose is preparing to move back to New York to pursue her publicity career. She visits the diner to give Twyla some clothes she’s decided not to take with her. (Much as Stevie is the only employee we ever see at the motel for most of the series, Twyla is the only employee we ever see at the diner.) When Alexis comments that she doesn’t want Twyla to pay for the clothes because she’s seen how people tip there, Twyla reveals a secret:

Twyla: Alexis, between us, I don’t do this for money. I won some money in the lottery a few years ago.

She further reveals this amounts to tens of millions of dollars, and dates back to when the Rose’s had first arrived in town. So why would she continue waiting tables?

Twyla: If I’ve learned anything from how my mom spent the money I gave her, It’s that money can buy a lot of snowmobiles, but it can’t buy happiness. So it’s about how you live your life. You know, doing what makes you smile. And being here, getting to hear your stories over the past few years, even the scary ones, that makes me smile.

This is the ‘theme stated’ moment, the theme of the show said aloud. Money can’t buy happiness, it’s about how you live your life. This is a perfectly sensible sentiment, but its made absurd to the point of self-parody in this scene. I’ve known lots of people who’ve waited tables, and I can say categorically that none of them would continue doing it if they won tens of millions in the lottery. Waiting tables is a hard, shit job. But as we’ve explored, the problems with blue collar wage labor don’t seem to exist in the Schitt’s Creek universe, and Twyla in particular exposes like an open sore how out-of-touch the writers seem with the literal subject of their work.

Alexis’ response then modifies the theme statement in a telling way. She says “Every now and again, spending like a little bit of money on something really special, it might not buy you happiness, but… it can definitely help make you smile.” And what is the thing this inspires Twyla to buy with her wealth? Why, it’s the diner she works at, transforming her from a wage laborer to yet another small business entrepreneur.

Thus we have my whole case.

Schitt’s Creek wants to tell us that wealth has a corrosive effect. But it can’t quite ever bear to consider what the lives of the impoverished are like, and creates a world in which all anyone needs to do to succeed financially is to become an entrepreneur and work hard, as if systemic issues have nothing to do with it. And this is a fundamentally right wing conception, one that lines up with Jerry Rubin’s yuppie “entrepreneurial capitalism will save us all” proposition I talked about in the Chicago 7 episode. This is Reagan’s America, and it’s an ethos that the right uses to justify cutting public assistance because it’s going ‘make people dependent on the government’ and ‘encourage people not to work’. After all, if anyone can make it with a business plan and a little gumption, if poverty is a choice, then offering assistance is just abetting laziness for the undeserving poor. (Granted that Johnny Rose does get unemployment assistance early in the series but not much is made of it.) And the dumb luck the characters in this show consistently experience becomes a stand-in for the privileges that the privileged are blind to, the way whiteness, or education, or having family that can help you out, or any of a thousand other things alters the playing field.

So what you get is a show that makes overtures to culturally liberal values like gay marriage while giving us yet another economically conservative, neoliberal worldview. And I don’t even think the writers of the show were aware they were doing this; this worldview is so ingrained in their minds it’s invisible. This is why the right’s frequent claims of “liberal media” are such a joke, honing in entirely on the most surface level signifiers while the actual themes of our media are by-and-large made by a class of people for whom neoliberalism has done pretty well. It’s also why in America we have one center-right party and one far-right party, because Democratic politicians are mostly from that self-same class of people as the Republicans and media creators, going to the same schools and given the same educations. (Ted Cruz and Barak Obama are both graduates of Ivy League universities and Harvard Law School, as an easy example.)

Could a show like Schitt’s Creek that actually confronted the problems of small town North America work? I could imagine something like an updated All in the Family, where at least some of the inhabitants of the town were the kind of racist Trump supporters that, for example, Rosanne Barr turned out to be (unlike the sanitized version of the Trump supporter that she portrayed on the revival of her television show). One could imagine them actually meeting people who lived in trailers or crumbling old houses they couldn’t afford to keep up, people in their 30s who still lived with their parents, people whose livelihoods had disappeared when nearby industries moved offshore. A show where the lead characters maybe don’t find it quite so easy to extract themselves from the mire, or find themselves caught in cycles of credit card debt trying to keep afloat.

That show might not be as much of a warm blanket in troubled times. But it might be the show we need.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- On the urban-rural divide of Christmas movies

- The TV Tropes entry for From New York to Nowhere

- Ted Koppel’s piece on The Andy Griffith Show and modern politics

- A fascinating video that explains how the ethos of “personal responsibility” leads naturally to white nationalism

- How and why small towns are in decline

- How teen birth rates are higher in rural areas

- On the myth of welfare dependency

If you enjoyed this please tell your friends, since word-of-mouth is how projects like this grow.

This project is brought to you by my Patreon. For as little as $1 an episode, you can get early access to episodes and exclusive author’s notes at Patreon.com/ericrosenfield.

I’d like to thank my Patrons, Kevin Cafferty, Wilma Ezekowitz, IndustrialRobot, Hristo Kolev, Benjamin Pence, Jason Quackenbush, Nancy S. Rosen, and Arthur Rosenfield.

2 comments on “The Confused Ideology of Schitt’s Creek”