Audio Version | YouTube Version | Get this in your Inbox

There’s a moment at the climax of the Doctor Who episode “Kerblam!”, where the titular time traveling alien known only as the Doctor confronts a terrorist. This villain seeks to murder hundreds of innocent people in an effort to disgrace and collapse the Kerblam! Corporation, an interstellar Amazon.com analog he blames for rampant unemployment as it’s automated the bulk of its workforce.

“We can’t let the systems take control!” He exclaims.

“The systems aren’t the problem,” the Doctor replies. “How people use and exploit the system, that’s the problem.”

These sentences have been justly seized on as reactionary by segments of the viewing public, including a recent article in the Guardian. In context, if we’re being charitable, the Doctor is specifically referring to the AI itself, consistently referred to as “the system” throughout the episode. Therefore, the idea is that the computer itself is a tool, and it can only be judged by those who wield it. But it’s just another way in which the episode refuses to face or even acknowledge the actual problem it’s trying to grapple with in any real way.

The premise is simple and fairly typical Whovian fare. The Doctor gets a message asking for help from the homeworld of the far-future Kerblam! Corporation. She and her human companions infiltrate the corporation by acquiring jobs, and there they proceed to ferret out the mystery of why employees are turning up dead.

Part of the narrative is how most of the employees have been replaced by robots, and the robots and their AI controller are assumed to be the most likely culprits (fitting in with a long tradition of Who episodes where contemporary technological fears are channeled into tales of murderous androids and megalomaniacal computers). This is, however, a feint and in truth a relatively clever one, where the culprit actually turns out to be the aforementioned terrorist, whose plan is to essentially put a bunch of bombs in boxes Kerblam! is shipping out to cause a backlash that will shut down the corporation which has automated away so many jobs. And the message asking for help was actually sent by the AI itself.

The episode is thus primarily about the oncoming threat of technological unemployment, where technology has rendered the bulk of labor unnecessary. In other words, it’s a ‘ripped from the headlines’ premise in a world where management consulting firm McKinsey & Company predicted that by 2030, one third of all US workers could be unemployed due to automation, and a recent White House report posits that 83% of jobs making less than $20 per hour will be subject to automation and replacement, and between 9% and 47% of jobs may become irrelevant.

And even the human jobs that Kerblam! does have are described as completely unnecessary, dull, repetitive labor only assigned to humans as a sop to laws that require an at least partially human workforce. “Work gives us purpose, right?” Says one of the people thus employed. “Some work, maybe,” accurately replies one of the Doctor’s companions.

The Kerblam! Corporation is shown to be completely unregulated; it’s even responsible for policing itself, leaving no one to call as people are murdered throughout the episode. And while this point isn’t dwelled on, it’s a self-evidently horrifying end result of a corporation being beholden to no one.

The episode, in other words, presents some evidence of knowing what the real problem is: rapacious, unchecked corporate power and dispelling the myth that creating bullshit jobs that no one really wants is a suitable solution to technological unemployment. Except the climax and denouement undermine all of this, where the only person really trying to change the system is portrayed as a terrorist, the system itself declared not a problem, and ultimately the corporate functionaries vowing to solve the problem by filling the company with more humans working bullshit jobs. And so terrorism (even in failure) is the only thing that succeeds at creating material change, but really that material change is hardly anything at all. Which could be seen as a satire of capitalist society, if there were any evidence the episode wanted it to be seen as such.

Missing completely from the equation, after all, are the owners of the company, the executives, board members, and investors, who actually have power over the situation. In all the talk of rampant unemployment in the galaxy, there’s no mention of a wealth gap, of the wealthy at all, simply a “system” nebulously being “used”. The real question hanging over everything is never asked: who’s fault is it that people are starving simply because they don’t have jobs? Why should they need jobs at all when most of the jobs can be automated away? What’s the purpose of forcing your population to starve or work boring, soul-crushing jobs when the jobs are completely unnecessary and there’s enough wealth for everyone to live a fulfilling life if we simply shared it more equally?

And so we arrive at the expression coined by Slavoj Žižek (paraphrasing Fredric Jameson) that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of Capitalism, something proven over and over again by Doctor Who’s depiction of the former and lack of depiction of the latter.

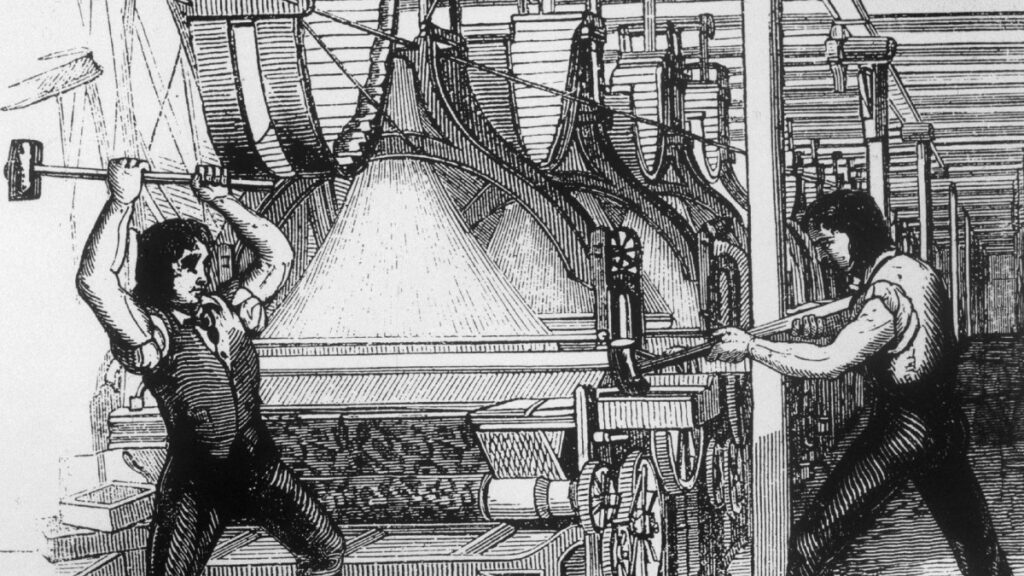

Terrorism as a response to automation has real-world antecedents. In the early 19th century, English textile factory owners began replacing highly-skilled artisans with mechanized looms that could be run by low-paid laborers. In 1811, the artisans began to respond to the sudden loss of their livelihoods with violence, breaking into factories and smashing looms to pieces. In the manifestos these artisans would subsequently release, they’d credit their movement to one General Ludd, a fictional, Robin Hood-like military leader.

The British government responded by making the destruction of looms a capital offense and sending in the military. Many artisans were gunned down, others hanged, still others merely shipped off to penal colonies in Australia. The back of the movement broken, the textile companies were free to “modernize” their factories and the term “Luddite” came to refer to anyone who hates and fears modern technology.

Missing from the typical version of this narrative is the fact that the Luddites weren’t originally opposed to mechanized looms. Resistance only happened when it became clear that the factory owners were going to replace them with cheap, unskilled labor. And the artisans’ first response was to suggest measures to preserve their quality of life–a minimum wage, guaranteed pensions, and the establishment of safety standards for these dangerous new machines. After all, the owners stood to make more money than ever. Why shouldn’t they share it with the people actually doing the work? This logic might in fact have carried more weight in earlier decades, but the writings of Adam Smith had been recently published, and the minds of the ruling class swam with ideas of the fundamental value of self-interest and the “invisible hand” of the market working to the benefit of all.

While concerns at the time that mechanization would lead to mass unemployment would turn out to be unfounded, as the 19th century wore on the bulk of skilled artisan jobs transitioned into relatively unskilled industrialized wage labor. And with no check on business owners’ exploitation of their employees, the leisurely lifestyle of the artisan (who could dictate their own hours) gave way to a situation where by 1890 a US government study found that laborers across industries worked an average 100 hours a week. And the hazards of factory conditions during this period are the stuff of legend, with workers routinely ending up maimed or dead without any of the modern expectations of workers’ compensation, health care, or life insurance.

This state of affairs wasn’t an accident of industrialized capitalism, it was the obvious end-result of it, where business leaders and their investor co-owners do whatever they can to maximize profit over all other considerations, especially the welfare of labor.

Workers unions and their allies in the Progressive movement battled against this system (often literally as the police, military, and mercenaries were turned against strikers) and ultimately won concessions including the 8-hour-day and the 2-day weekend that we now take for granted. Part of the rational for these measures, taken during the Great Depression, was to reduce unemployment, since businesses would need to hire more people to do the same amount of work. Indeed, there was a tantalizing idea in the minds of Progressives at the time that mechanization could actually free us from work. Economist John Maynard Keynes, for example, famously predicted in 1930 that people would soon work 15-hour weeks with no loss of pay. By the middle of the 20th century, taxes on the wealthy had gone up dramatically, social security had been created, and things had greatly improved for most Americans in economic terms. That all shifted with the resurgance of laissez-faire free market ideals in the form of Neoliberalism beginning in the late 70s, where tax cuts and large-scale deregulation gave the wealthy the means to begin the process of destroying the hard-won middle class.

As a result of this Neoliberal agenda, today the wealthy have taken all the gains in productivity and labor efficiency that automation and computerization have allowed and hoarded it all for themselves, leaving 78% of Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck and 61% of Americans unable to cover a $1,000 emergency and having to turn to GoFundMe to cover their medical expenses. And this is all felt more keenly in the time of a pandemic.

Keynes and his cohort would have seen the modern rise of technological unemployment as an opportunity rather than a crisis, where we as a society could reduce the number of hours people have to work just as progressives did during the Great Depression, or even do away with work as a prerequisite to survive altogether using strategies like Universal Basic Income or better yet Universal Basic Assets or some other scheme funded through expanded progressive taxation of the wealthy few who can afford it better than ever.

But conservatives, as alluded to in the Doctor Who episode, would have it that humans need work to give us purpose. However, spending the bulk of your life in the soul crushing tedium of a position that could just as easily be performed by a robot doesn’t sound like much of a purpose, especially while the children of the rich have unlimited opportunities to make their life however they please simply by virtue of their birth.

In a world where the middle classes have been gutted while the burgeoning lower classes find themselves at the sword point of the aforementioned rise of technological unemployment, “Kerblam!” represents a situation where the house is on fire and someone just wrote a parable where the villain wants to blow up the house with everyone in it to put the fire out and in the end the heroes resolve to stay cool by drinking more ice water.

And yet, for so many, this seems to be the limits of their imagination, not just for this problem but all the major problems our society is currently facing. It’s apiece with telling those concerned about Global Warming to drive electric cars and recycle more. The problem isn’t the system, after all. It can’t be the system. I mean, there’s nothing better than the system. As Margaret Thatcher would have it, there’s simply no alternative.

And so there’s nothing left for us but to be thankful we have jobs at all while the world around us burns.

# # # # #

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed it, please tell people about Literate Machine. Word-of-Mouth is how things like this grow. Everyone stay safe and don’t forget to wash your hands!

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Who Were the Luddites from History.com

- Article in the Guardian about Doctor Who’s Issues with ‘Wokeness’

- Article on CNBC about McKinsey & Company’s report about automation

- Article on Quartz about technological unemployment including description of the White House report

- The White House report on Automation written in the Obama era

- Article about the Origins of the 40-hour Workweek

- Article in the Guardian about Keynes and the workweek of the future

- Article in Vox about how the wealthy have taken all the productivity growth for themselves

- Forbes article about Americans living paycheck-to-paycheck

- Huffpost article about American being unable to afford an emergency

- Forbes article about people using GoFundMe to cover healthcare costs

- Information about Universal Basic Assets, an alternative to Universal Basic Income that gives people greater power over the means of production in addition to money

- Wikipedia’s article on Neoliberalism (not to be confused with American Liberalism or Classical Liberalism which are three different things).

- Thatcher and the phrase “there’s simply no alternative” on Wikipedia

Pingback: How Can I Save You? 12 Monkeys and the Coronavirus – Literate Machine

Pingback: Pixar’s Soul: Finding Yourself Under Capitalism – Literate Machine

Pingback: How Capitalism Becomes Feudalism (Severance and Technofuedalism) – Literate Machine