Or Who Deserves the Future

Video Version | Audio Version | Get this in Your Inbox

Star Trek (1966-1969) was in many ways an exploration of the idea of utopia, of what happens when people look around and say ‘surely, we can do something better’. In episode after episode, the starship Enterprise encountered some paradise which would ultimately, inevitably, be revealed to be some sort of fiction, whether the totalitarian “unity” of “The Return of the Archons”, the brainwashed prisoners of “Dagger of the Mind”, or the computer-controlled primitives of “The Apple”. We also see a parade of strivers trying to find or create utopias, like the charismatic eugenicist Khan Noonian Soong in “Space Seed” or the band of hippy hijackers of “The Way to Eden”. However, the strange thing about all these flawed Utopias that separates Star Trek from most similar works of its type is that they all exist in contrast to the one utopian vision that actually works without catches or downsides, the Federation itself.

Admittedly in The Original Series the Federation was at best loosely sketched, merely backdrop to a show pitched as “Wagon Train to the stars”, which is to say a Western-style adventure show set in space. In fact, at first Captain James T. Kirk said he came from the “United Earth Space Probe Agency”, with the Federation only mentioned in episode 18. Still, even the words ‘United Earth’ implied a planet in which war was a thing of the past, and to underscore this the second season brought on a Russian (but not Soviet) crew member while in real life America was in the depths of the Cold War. Further, it’s made explicit that this future is one where racial and gender prejudices are a thing of the past (even if the primary leads were still white men (though one played a bi-racial alien), and there were at maximum precisely two non-whites in the bridge crew and one woman following the booting of Grace Lee Whitney after eight episodes). In “Let This Be Your Last Battlefield”, Captain Kirk describes the Federation as a place where “we live in peace with full exercise of individual rights.” And in “Whom Gods Destroy”, he more poetically calls it “a dream that became a reality and spread throughout the stars.”

But it was only while engaging with fandom that Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry discovered how this idea of a future free from the kind of strife and oppression of the present hit a nerve, particularly during the social and political tumult of the 1960s and 70s. And so after The Original Series‘ cancelation, the idea developed and churned in his mind until it’d blossomed into a fully moneyless, classless society. This version of the future made it to screen with Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1987. As ship’s Counselor Deanna Troi describes to Mark Twain in the midst of a time travel escapade:

TROI: Poverty was eliminated on Earth a long time ago, and a lot of other things disappeared with it. Hopelessness, despair, cruelty.

TWAIN: Young lady, I come from a time when men achieve power and wealth by standing on the backs of the poor, where prejudice and intolerance are commonplace and power is an end unto itself. And you’re telling me that isn’t how it is anymore?

TROI: That’s right.

Over the course of the series, we discover that the Federation is a place not only where poverty is gone, but also the need to work to survive. Replicators produce almost anything one can imagine from basically nothing, eliminating scarcity. A Federation citizen could join Starfleet and explore the stars if they wanted, or spend their life on an arts colony or a pleasure planet. People of the Federation have a kind of freedom most of us couldn’t imagine.

In a sense, though, there actually was a catch to Roddenberry’s imagined future, if not the one you might expect. Unlike in The Original Series, for The Next Generation he said that humans had matured not only out of poverty and want, but from interpersonal conflict itself. The people of the Federation would “never let their passions overwhelm them”, and he even included former lovers in the form of Commander Riker and Counselor Troi (who acted as the ship psychiatrist, because psychological maturity is an ongoing process) to show people who’d broken up but still remained friends without any animosity. (In other writing, Roddenberry demonstrates a fondness for polyamorous relationships as well, though there was only so much he could put into a prime time show in 1987.)

This notion has two major problems. The first and most obvious is that interpersonal conflict is one of the key drivers of contemporary drama, and so this edict constantly frustrated the show’s writers who had to come up with elaborate ways to prevent the show from becoming too repetitive and bland (and led to successive Star Trek shows increasingly including non-Federation cast members or, in the case of Enterprise, taking place before the creation of the Federation itself).

The second problem is philosophical. It creates the impression that in order to achieve economic freedom, one would need to almost shed one’s humanity, to become psychologically perfect and worthy. For Roddenberry, this was a natural extension of his conception of the Vulcans and The Original Series‘ most popular character, Mr. Spock. As a race, the Vulcans had perfected their minds through rigorous psychological training so that they could approach any of life’s problems from a place of perfect logic and reason. And it’s easy to see how such an idea would appeal to someone like Roddenberry, who’s personal life could charitably be described as “messy”, including numerous affairs, divorce, drug addiction, and an intransigence and troublesomeness so severe it would get him successively removed from each of the three versions of Star Trek he’d created (The Original Series, the film series, and The Next Generation).

And so the implication is that to get to a utopian future its necessary to change ourselves first, that systemic change only arises from personal change. It’s also easy to read this as a kind of confirmation in general that building a society around cooperation rather than competition goes against ‘human nature’, that is our ‘natural’ human inclinations.

And these are notions that back to the birth of capitalism and the philosophical system that arose to justify it, and so in reality works against the utopian ideals it claims to represent. To understand why, let’s take a little slingshot around the sun and into a time warp.

Under Feudalism, class mobility was almost unheard of. All land legally belonged to the monarch, who parceled it out to nobles as fiefdoms, who in turn lived off the produce of the serfs and peasants in their fief. The dominant philosophical system of medieval Christianity taught an ethos of subservience to authority—peasant to lord, lord to monarch, and all before God and the Church—and greed and pride, those markers of growing above one’s station, were considered deadly sins.

However, with the rise of capitalism, the ostensibly peasant merchant class began gaining wealth on a level to rival the nobility for the first time, and with it power. A new philosophical framework emerged during what became known as the “Enlightenment”, one that emphasized the ideal of the “self-made man”, someone who through a combination of basic competence, grit, and inspiration, can master his own fate and rather than following the rules, bent them to his will and natural sense of justice. This is the archetype of James T. Kirk, a common man from Iowa so profoundly gifted that, leading his trusty crew, he can unwind and upend any false utopia he comes across. And in real life, it’s represented most fully by American founding father Benjamin Franklin, who went from an apprentice printer to a successful businessman, investor, inventor, public intellectual, and finally a revolutionary casting off the crown entirely in favor of a republic founded on Enlightenment ideals.

Franklin’s writing includes some of the earliest self-help material ever created. In The Way to Wealth, a collection of pithy adages culled from his regular almanac, Franklin advises hard work and industriousness in phrases like “early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy wealthy and wise”. His most fully realized self-help program however is found in his autobiography, which was required reading in American schools for generations. Here, Franklin describes how as a young man he made a list of 13 “virtues” that he felt he needed to follow in a “bold and arduous Project of arriving at moral Perfection”, including moderation, sincerity, and industry (described as: “Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions,” Franklin anticipating hustle culture). In a notebook, he made a grid with a column for each virtue and a line for each day, and would mark any day where he felt he’d made an offense against one of his virtues. (This pairing of industriousness with morality is what would later be described as the “protestant work ethic”.)

But there was a problem with these American notions of “liberty” and “freedom”, a contradiction in the heart of Enlightenment values most clearly expressed by Ben Franklin’s friend Thomas Jefferson writing “all men are created equal and endowed… with certain inalienable rights… among these are the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” while simultaneously owning chattel slaves.

Feudalism was an awful and highly inequitable system. However, it had some characteristics that might be surprising to modern people who have been conditioned to think of capitalism as a kind of state of nature. As mentioned, all land legally belonged to the crown, and thus the state. (In practice, of course, the extent and reality of this legal principle varied based on region and time period, but the general idea stands.) For the vast majority of people, the peasantry, ownership of land wasn’t a concern. Serfs were forbidden from moving off their farms in any case, essentially treated as features of the property for the lord like a tree or a pond, and peasants and serfs often farmed and grazed “commons”, land shared by everyone. (The so-called ‘tragedy of the commons’ is a myth dispelled by almost every actual commons in history.) However, with the emergence of capitalism, lords increasingly enclosed their land to use for private enterprise, forcing now landless serfs into factories where they labored typically in horrific conditions for subsistence wages. Indeed, indentured servitude and debt peonage often reduced formerly free people to slavery, and in the ‘company towns’ that eventually arose people might be paid in a company scrip that could only be used at a company store where they’d intentionally be paid actually less than they needed to survive so that they perpetually went into debt and thus debt peonage. And, of course, millions of people in Africa were simply kidnapped and forced into entirely unveiled slavery for the sake of their owner’s profits. For people born with certain advantages, like Ben Franklin who could read and write and whose father could acquire an apprenticeship for him, becoming “self-made” might be possible. But most people for most of the history of capitalism were just as trapped in their subservient condition as before, if not put into far worse positions. Someone telling these folks that they could improve their class status in society by improving themselves would be laughable.

Enlightenment philosophers would posit “freedom” as being free from state interference, and thus interference by the crown that had dominated the previous system. They would propose for the first time that people had “natural rights”, including a right to equal treatment under the law, freedom of speech and assembly, and all the other things that guaranteed they could criticize the state that might oppress them. And most especially they had a right to property, to own things like land and businesses, and to enter into contracts with each other free from state meddling, a notion buoyed by works like Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776), which proposed that when left unregulated commerce would inevitably find the most efficient and productive economic modes through the “invisible hand of the market”. Within this framework, the best thing the individual could do not only for themself but for the public interest would be to pursue their own “enlightened self-interest”, to improve both themself and their place in society. (This philosophical system has a name, though it’s confusing for Americans. The name is ‘Liberalism’, which in America is usually referred to as ‘Classical Liberalism’ to distinguish it from the very different notion of American Liberalism. This is also why the resurgence of this philosophy today is called ‘Neoliberalism’, or the new liberalism.)

Roddenberry sought to contrast his post-capitalist Federation on The Next Generation with a new Big Bad species who based their entire society around rapacious, unchecked capitalism and the pursuit of profit: the Ferengi. (It should also be noted, though, that the Ferengi illustrate Roddenberry’s continued blind spot to insensitive cultural depictions of ethnic groups which also marked the early black-faced Klingons; with their hunched figures, prominent noses, and appetites for non-Ferengi women, the Ferengi can be easily seen as Jewish caricatures.) The Ferengi, of course, never really gelled as feared antagonists, too comical to be intimidating. But still, particularly through the Ferengi character Quark on the show Deep Space Nine, the Ferengi became the primary way that Star Trek was able to comment directly on capitalism.

Liberal philosophy is best expressed in Star Trek in the Deep Space Nine episode “Prophet Motive”, where Quark defends the Ferengi to a group of nearly omnipotent aliens.

QUARK: There’s nothing wrong with acquiring profit. … Our ambition to improve ourselves motivates everything we do. Without ambition, without, dare I say it, greed, people would lie around all day doing nothing. They wouldn’t work, they wouldn’t bathe, they wouldn’t even eat. They’d starve to death. Is that what you want?

The aliens dismiss this argument as specious, obviously people wouldn’t starve to death without profit. And in context, the statement is downright ludicrous with the Federation right there as a counter-example. But here in the real world you’ll find many people today who agree with Quark, including people writing under this clip on YouTube, ‘Quark is right’. As immoral financial trader Gordon Gekko put it in Wall Street (1987), “greed is good”. In the capitalist mindset, greed, ambition, and self-improvement are all intertwined, and the best and indeed only way to improve society is through improving the self. In this view, because greed and self-interest is the ‘natural’ focus of human behavior, trying to create any kind of more egalitarian society at all, a society in which people share the products of their labor, is ‘unnatural’ and ‘goes against human nature’. This despite the fact that humans lived primarily in egalitarian bands in the thousands of years before the rise of agriculture, that native Americans before the arrival of the Europeans often held goods in common for the whole tribe (eg. the Iroquois Confederation), and so on. This is not to say tribal societies were perfect, and in fact they were highly varied in form and structure, simply that they were almost always far more egalitarian, as were early examples of cities like Çatalhöyük, which thrived over 9,000 years ago in what’s now Turkey, in which almost all the dwellings were the same size, indicating a lack of material hierarchy. This recognition (and subsequent romanticization) of primitivism shows up in Star Trek as some of the only non-Federation examples of successful utopianism, for example in “The Paradise Syndrome” where Kirk gets amnesia and joins a tribe of Native Americans who’ve been mysteriously transported to an alien planet (though this depiction, as frequently with ‘noble savage’ narratives, is both condescending and racist). We see this idea of primitivism as utopian again in Star Trek: Insurrection (1998), where a group of aliens has decided that the only way they can live in peace and harmony is to abandon all advanced technology and live lives of simple farmers.

If there’s a problem with the Ferengi as conceived, it’s that their critique of capitalism is too simplistic. I wish that one of the so-called Rules of Acquisition, the appropriately self-help-style text the Ferengi treat as scripture, were more like the first ‘habit’ from the ultra-capitalist self-help guide The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Take responsibility for your life, don’t be a victim. In other words, any systemic or structural problems that might be standing in the way of someone’s happiness or success–socio-economic background, race, education level, and so on–are just excuses for your lack of success that you could overcome through grit and determination, that you like anyone could still be a ‘self-made man’. Capitalists like to talk a lot about having ‘equality of opportunity’ not ‘equality of outcome’, and yet even pointing out that not everyone has the same equality of opportunity is something they’ll dismiss as victim-talk. So what if without a good education or support you have no choice but take a terrible job or starve? You have the same ‘freedom’ as everyone else, don’t you? You shouldn’t expect anyone to give you a handout. Capitalists will say ‘if you give a man a fish he’ll eat for a day, but teach him to fish and he’ll eat for a lifetime’, and yet when you suggest funding educational programs to ‘teach them to fish’ you discover what they really want is to leave a man to starve to death and then feel smug because they deserved it and did it to themselves.

There’s an episode of Deep Space Nine that begins to address this problem and how to go about solving it. In “Bar Association”, the employees of Quark’s bar, led by Quark’s brother Nog, decide to form a union. This is an action that would be outright illegal on their home planet Ferenginar—capitalists also love to talk about freedom of association except when its their employees associating to demand better salaries and working conditions. As Rom complains, “You don’t understand. Ferengi workers don’t want to stop the exploitation. We want to find a way to become the exploiters.” After all, everyone is free to become a robber baron under capitalism, if only they dream big enough.

The space station Deep Space Nine, on the show a unique collaboration between the Federation and the non-Federation world Bajor, is not Ferenginar and the bar staff strike. This leads to the only time in my knowledge that Karl Marx has been quoted in Star Trek, as Rom confronts his brother:

QUARK: Rom, can’t we talk about this?

ROM: There’s only one thing I have to say to you. (reading) Workers of the world, unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains.

QUARK: What’s happened to you?

Of course being a television show in the modern entertainment paradigm, the story still must focus on an individual and their ‘character arc’, how the story personally effects them and their development. In this case, Nog goes from being subservient to his brother to a brave strike leader, and in the end he’s rewarded with a better job and even gets the ‘girl’. While in reality, systemic change for the benefit of those below is always achieved through group action and organization, contemporary television demands a ‘hero’. Every episode of the Star Trek franchise that deals with class conflict must be resolved chiefly through the actions of a single character; for example The Original Series episode “The Cloud Minders”, and Voyager’s “Critical Care” both depend on the lead character kidnapping one of the privileged people and transporting them to the place where the poor live to turn the tables and show them the error of their ways. And this focus on individual heroism to solve social problems plays well with the liberal idea that great things happen by the will of great men, singular geniuses born to lead and uniquely capable of remolding society. You can see how this might lead naturally to authoritarian thinking, that what we all really need is a strong hand at the top to steer the ship without interference by lesser people, as opposed to the messy and sometimes frustrating process of working collectively together from below as a democratic whole.

How Deep Space Nine ultimately resolves the Ferengi class consciousness storyline becomes a perfect illustration of this problem. Quark and Rom’s mother Ishka becomes something of a feminist activist. She then lucks into a relationship with Zek, the Grand Nagus, who basically functions as the CEO/dictator of the entire Ferengi Alliance. Through her influence, the Ferengi implement a series of what are essentially Social Democratic reforms, as Quark discovers from another Ferengi, Brunt:

BRUNT: You haven’t been keeping up with the latest reforms, have you? Zek instituted progressive income tax three months ago.

QUARK: You call that a reform? Taxes go against the very spirit of free enterprise. That’s why they call it free.

BRUNT: The government needed revenues to fund the new social programs. Wage subsidies for the poor, retirement benefits for the aged, health care for—

QUARK: Stop, stop, stop! I had no idea things had gotten so bad. This is all Moogie’s (Ishka) fault. She’s been polluting Zek’s mind with notions of equality and compassion. Whatever happened to survival of the fittest? Whatever happened to the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer? Whatever happened to pure, unadulterated greed?

BRUNT: Things change.

Ultimately, Zek and Ishka retire to a pleasure planet after appointing Rom the new Grand Nagus. (For a while it bothered me that they would choose an electrical engineer with no political experience for the role, until I realized that an absolute ruler appointing their own entirely unqualified step-son to secede them is actually pretty in keeping with history.) While making sense in terms of storytelling and entertainment, this is not how progressive political change happens at all. No progressive policies have ever been passed without enormous pressure from organizations and activism from below; it’s not about one person heroically steering society to a better world, but the people united doing it together. Imagining the Grand Nagus changing Ferenginar without public pressure is like imagining LBJ and the Democrats passing the Civil Rights Act without the Civil Rights Movement marching in the streets. (Indeed, one problem with how the Civil Rights Movement is often portrayed in media and in our collective imagination is its own focus on heroic figures, chiefly Martin Luther King, Jr., which makes it easier for culture to quietly sand off the fact that he was a fervent socialist and try to delegitimize further anti-racist movements like Black Lives Matter by absurdly claiming that he wouldn’t have supported them. As if the white establishment was so enthusiastic about Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Movement he represented at the time (spoiler: they were not).)

Which brings us back to Rom’s favorite leftist thinker, Karl Marx. We’ve already seen two different definitions of ‘liberty’ and ‘freedom’ that appear to be at odds with each other. There’s the freedom of being in the Federation, a freedom to spend your life doing whatever you please. And there’s the freedom of the Ferengi, the freedom to own property and businesses and enter into contracts with others for your own benefit without interference from the state or anyone else. Marx pointed out that there were always people who had the first kind of freedom, whether it was the slave owning ‘citizens’ of ancient Rome and Greece, the nobility of the feudal era, or the wealthy owners of capital under capitalism, whom the second kind of freedom seemed tailor-designed to benefit. Further, the business owner became wealthy by capturing the profit of their business while paying their employees as little as possible given the job market. In other words, their freedom was supported by the labor of those beneath them, just as the freedom of the feudal lord was created by the labor of the peasants and serfs on their fiefs.

What if there might be another way of doing things? What if the workers controlled the businesses themselves? What if they held the land in common like their peasant ancestors had, rather than paying rent to some landlord? What might society look like then?

This is a deceptively powerful notion.

Imagine for a moment you have a business that creates widgets. An invention comes along that allows the business to make the same number of widgets in half the time. Under capitalism, the business owner or owners might then fire half the employees, and thus be able to make the same revenue with half the labor costs. However, if the workers controlled the business, they might vote to keep the same number of employees at the same salary, but work half the number of hours. Thus who controls the business determines if the workers have the power to choose between profit and freedom.

Of course, this sort of business already exists, it’s called a workers co-op, and there’s thousands of them all over the world with the largest group of cooperatives being the Mondragón Corporation, a federation of cooperatives in Spain employing nearly one hundred thousand people.

But Marx didn’t just want cooperative businesses. He wanted a cooperative society. Inspired by the Paris Commune of 1871, he imagined, in the first draft of The Civil War in France (published the same year), the whole of France as ‘self-working and self-governing communes’ using universal suffrage to elect representatives to a national council that would administer ‘a few functions for general national purposes’ including (as he said in an address on the subject and book later) regulating ‘national production upon a common plan’. But Marx also warned against creating ‘recipes for cook-shops of the future’. An egalitarian society should not be planned from on high by anyone, not even him, it should be self-organized from below by the people themselves. And contrary to his image as a revolutionary absolutist, Marx believed that some countries might be able to transition to this sort of ‘communism’ peacefully through representative democracy once universal suffrage had been achieved. Communism in Marx refers simply to a situation where the ‘means of production’ are owned communally by the people and run for the public benefit rather than being owned by a handful of wealthy capitalists and run for the profit of their shareholders. Marx wanted to abolish, in other words, what he called ‘private property’, which is to say land and businesses. This term has caused no end of confusion though, since Marx distinguished ‘private property’ from ‘personal property’, which is stuff like your tooth brush that no one wants to take away.

In the popular imagination, of course, Communism has come to mean something else entirely. The term has become synonymous with the Soviet system especially as developed by General Secretary Joseph Stalin, a centralized and undemocratic bureaucracy supervising not only every aspect of the economy but seeking to colonize as well the minds of its populace and purge out any dissenters as ‘enemies of the people’ in a way starkly similar to Fascist Dictator Benito Mussolini’s conception of ‘totalitarianism’. This version of ‘Communism’ would be basically unrecognizable to Marx. Communism, in Marx, is global, stateless, classless, self-organizing, and fundamentally democratic. But in between capitalism and communism, you’d have what Marx called the “dictatorship of the proletariat”—which didn’t mean a dictatorship in the modern sense, but simply just a situation in which the workers would be in charge. (Engels even said the ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ would take the form of a democratic republic.) Following the First World War, Revolution, and Civil War that had laid waste to the former Russian Empire, Soviet founder Vladimir Lenin decided to shore up the economy by both allowing small business ventures again and by having his government take over (or remain in control of) major industries. But a situation where a few unelected private capitalists running businesses have been replaced by a few unelected bureaucrats isn’t communism, or even socialism. It’s what Lenin himself called ‘state capitalism’. And it was supposed to be temporary as the Soviets worked towards global revolution, until Stalin decided, against Marxist doctrine, that the Soviet Union could establish ‘communism in one country’ and made state capitalism permanent.

These decisions were not without critics on the left. For example, contemporary Communist thinker Rosa Luxemburg wrote,

To be sure, every democratic institution has its faults and limitations, which it has in common with all human institutions. But the remedy discovered by Lenin and Trotsky, the abolition of democracy, is worse than the evil it is supposed to cure, for it shuts off the lifespring from which can come the cure for all the inadequacies of social institutions.

Rosa Luxemburg, The Russian Revolution (1918)

Socialism was always supposed to be democratic. After all, if the workers aren’t in control of the means of production, you don’t have socialism at all.

Of course, capitalists are happy to point to this and call it evidence that ‘socialism never works’. But then, in the capitalist mind, the Stalinist system is the negation of capitalism’s focus on the individual. And this negation of the individual has been dramatized in Star Trek in various ways , such as in The Original Series episode “The Return of the Archons”, where a population lives under the absolute control of a fanatical computer. But the most full version of this is The Borg, cybernetic beings who spread peace and harmony through the universe by transforming all beings into mindless drones. Among the Borg, the queen is the only one with anything resembling actual freedom, living the ultimate dream of the totalitarian dictator where their subjects thoughts themselves are merely an extension of the leader’s will.

Channeling this, a capitalist will take any loss of power to the state at all, even such innocuous things as universal healthcare or social security under a functioning democracy as akin to Stalinism and essentially evil. The Ferengi want you to think there’s no option between them and the Borg.

However, there’s a strange contradiction here, isn’t there? As we’ve explored, capitalist corporations have a history of reducing their workers to as abject conditions as possible, whether that was literal slaves, indentured servants, debt peons, undocumented immigrants, or simply workers employed at far below a living wage. Open slavery still exists in America, after all, where convicted prisoners are forced to work for pennies or for nothing to make products of for-profit businesses. But this is part-and-parcel with the fact that capitalist corporations are themselves not democracies, that their CEOs and boards of directors have the same sort of absolute power reserved in the political world for dictators and oligarchs.

Neoliberal politicians insist they want ‘small government’, and yet always seem to provide massive subsidies to private corporations, shifting our tax money into capitalist hands. But the truth is, of course, whatever so-called anarcho-capitalists tell you, there is no capitalism without the government. Capitalism depends on contracts, on binding agreements between employer and employed, and between different businesses to coordinate production and distribution. As the Grand Nagus himself once said, “contracts are the very basis of our society”. And a contract is only as good as the legal system in place to enforce it. The government is the entity that grants charters of incorporation and creates the conditions—the rules—in which those corporations can operate, and thus every capitalist owes their winnings ultimately to the state and the system it governs which permits them to control production and capture profits. This is why the ‘anarcho-capitalist’ fever dream of corporations without government oversight would always devolve into feudal-esque warlordism, where power would accrue to whoever had the most powerful private security, much as political power on a national scale often goes to whoever has the most powerful army, whether or not their claims are legal, just, or ethical.

But then Neoliberals don’t actually want to eliminate the government. What they want to eliminate is any sort of commons and public welfare, anything that privileges the weak or the poor, anything that prevents them from taking as much money and power as they can while feeling justified that they deserve it, confusing privilege combined with rapacious, amoral greed and ambition for intelligence, worthiness, and merit. Meanwhile, they’ll preach an almost religious faith in the ‘free market’ to solve every possible problem and benefit everyone while reality demonstrates the irrationality and moral bankruptcy of this position every time someone dies because they can’t afford insulin.

In reality, the notion that ‘socialism never works’ is contrary not only to the reality the Paris Commune of 1871 or similar experiments like the anarchist communes of Revolutionary Spain or the Ukrainian Makhnovshchina which were all destroyed from the outside by authoritarians, or modern ongoing situations like the Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities in Mexico or Rojava in Northern Syria, not to mention various smaller communes around the world. But as Marx himself pointed out and as illustrated by the aforementioned destructions, this kind of pure egalitarian society is difficult to maintain in the midst of global capitalism, which is why he believed communism was only possible if it spread globally.

However, that doesn’t mean that socialist ideas haven’t accomplished great things. During the deprivations of the Great Depression, membership in socialist and communist organizations soared. Franklin Roosevelt was no socialist, but under the pressure of union, socialist, and communist power and the threat of mass action, he adopted 90% of the platform of Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party presidential candidate. Unemployment insurance, worker’s compensation, the abolition of child labor, social security, the 8-hour workday and 5 day workweek (though Thomas originally wanted 6 hours!), and minimum wages were all socialist ideas before they became mainstream, and we now have these things we take for granted thanks to the long efforts of socialist agitation, organization, and activism. And every one of them were at the time opposed by right wing businessmen crying “socialist” like a curse and promising they would ruin the economy and country and undermined our values of ‘freedom’. (It’s worth noting though that Roosevelt’s “New Deal” specifically carved out exceptions to worker rights in industries where workers were predominantly black in order to get the backing of Southern Democrats.) He also implemented British economist John Maynard Keynes ideas about using direct management of the economy in order to avoid the cyclical recessions that had plagued the 19th century.

The result, for America and most of the post-WWII west, was what’s now known (as dubbed by socialist thinker and founder of the Democratic Socialists of America Michael Harrington) as the “Social-Democratic Compromise”, coinciding with what economists term the “long boom”, a period lasting until the mid-70s of untrammeled growth, economic stability and prosperity, and a burgeoning middle class mostly free from the levels of abject inequality that marked the Gilded Age. (At least, for white people.) This is also, perhaps not coincidentally, the period that gave birth to Star Trek itself, a period where Democratic Socialist forefather Edward Bernstein’s vision of socialism growing gradually within capitalism as capitalism had grown within feudalism might be working.

Somewhat ironically, the same capitalist types who protested every one of these programs as ‘socialism’ will turn around when we say this is evidence that socialism works to lecture us that this isn’t socialism at all. But it is what Keynes referred to as a kind of ‘semi-socialism’. Private property—which remember, only refers to businesses and land—has obviously not been abolished, but large swaths of the economy and land have been brought under the regulation or proprietorship of the state which, at least ostensibly, is managed democratically by the people. Here in America, roads, parks, beaches, all sorts of forests and natural spaces, government buildings, and so on are all publicly owned, as is lots of public housing. And the government runs all sorts of businesses and business-like services, like the Post Office, libraries, public transit, schools, and so on, not to mention law enforcement and the penal system. Hundreds of municipalities run their own broadband internet access for their citizens, and the people in these municipalities are consistently the only Americans who express satisfaction with their ISPs. (This hasn’t stopped many red states from banning municipal broadband altogether, though, to protect the profits of corporate ISPs.) The US military, whatever other problems there are with it, is a massive, government-run institution that not only employs over a million people, but manages just the sort of centralized logistics of production, labor, and distribution on a scale that critics of central planning often claim only the free market can do. (And really, if market competition were always so superior to central planning, then Amazon would allow trucking companies to compete for its business rather than owning its own trucks. Every company that vertically integrates is a triumph of central planning over market competition.) And slews of regulations govern working conditions and seek to limit predatory business practices.

Other countries have gone considerably farther than the United States, of course. In the UK, all the hospitals are owned by the government and doctors and nurses are public employees, working for organizations whose remit isn’t profit but public welfare. The entire oil industry in Norway is owned and run by the government. In Vienna and Singapore, most people live in public housing and because it’s properly funded and managed the people love it and the fees they pay are far lower than rent would be on the open market. And far from destroying society, these publicly-run endeavors have often worked demonstrably better than private alternatives. Almost everyone already agrees that some things should be provided to the public at no or low cost.

The socialist suggests that maybe, just maybe, we could do more things this way. There are disagreements about how much should be controlled by the state or devolved into communities or independent cooperative businesses and family operations. Maybe some housing could operate the way Co-Op City does in the Bronx, a privately owned housing development where the bi-laws have strict rules about how much you’re allowed to sell your apartment for with a large portion of the sale profits going back to the co-op itself. There’s options. But the point is that the system where one person can control huge chunks of the economy and personally reap the greatest rewards from it is fundamentally unjust.

And here’s the real kicker about private property in the Marxian sense. While today 65.8% of Americans own a home (or live in a home owned by their family), homeownership rates for people under 34 is only 34%, falling 10% between 1960 and today as housing costs skyrocket and large firms buy up housing to transform into rentals, rentals they can then afford to warehouse to artificially drive up rental prices. The idea that housing should be an investment is one in which homeowners pursue policies that limit housing developments and affordable housing initiatives to protect their property values, and landlords vie to create conditions where they can charge ever higher rents. And so housing inevitably grows out-of-reach for first-time buyers who must give ever more of their earnings to landlords as ‘passive income’.

Meanwhile, only 8.9% of Americans can be described as a “business owner”. 10% of Americans own 89% of the stock market, and a lot of the rest is in retirement accounts and pensions controlled by a relatively small number of fund managers. And only 7% of Americans are landlords. The vast majority of Americans make the bulk of their incomes from wage labor, not capital ownership. In other words, not that many people in America actually own private property other than their own home. The economy of our “free market” is actually controlled by a tiny number of wealthy actors, and yet millions of Americans fight like mad for the right to keep it that way. In some ways its reminiscent of how in the antebellum South millions of whites were willing to fight to the death for slavery, despite less than 5% of southern whites actually owning any slaves (and only 1% owning large plantations).

Anyone can start a business, certainly, but everyone can’t. In a capitalist system, someone’s always left flipping burgers for peanuts or making your paper towels in prison, and in fact if someone doesn’t want to do this, capitalists through up their hands and exclaim ‘no one wants to work anymore’.

Is there private property in Star Trek? At first glance the answer is obviously yes. Captain Picard’s family, after all, owns a vineyard in France, Captain Sisko’s father runs a restaurant in New Orleans, and other, similar examples can be found. And yet, what’s interesting is that because almost all action takes place in the quasi-militaristic Starfleet (Roddenberry always compared it to the Coast Guard rather than the Navy), the stories of Star Trek mostly take place without private property, at least for Federation members. The Enterprise itself is the property of Starfleet, on a mission of exploration not profit. Thus the cast all live and work in a publicly owned environment, eating together in a mess hall, socializing in ten-forward, and sharing recreational facilities like the holodeck. Which means that while the Federation itself might have private property (though no money, so how private property is managed is unclear), Star Trek as a narrative vehicle is one that operates almost entirely in the realm of public property. (Though to be fair, the highly hierarchical organization of Starfleet is still not exactly a socialist ideal either.)

Anti-socialist forces were hardly dormant during the Long Boom. With the Cold War as cover, the Right were able to destroy communist and socialists groups, and the breaking of union power came soon after, aided by increasing automation and outsourcing that began to decimate the American middle class’s industrial base. In short, they rid themselves of the loci of worker power that had forced concessions on the ruling class in the first place. Then when the oil crisis of the 1970s, among other factors, caused the economy to falter, they struck, bringing back the Liberalism of the pre-war era as Neoliberalism. “The government is not the solution to our problems,” Ronald Reagan told the public, “the government is the problem.”

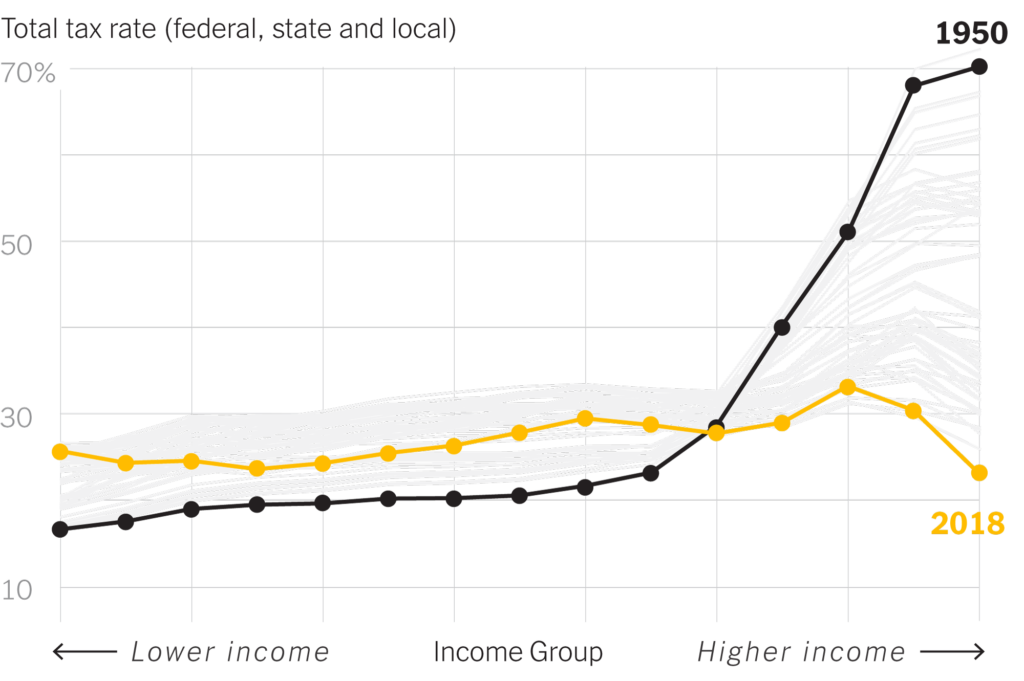

Over the past 40 years, the gains of the social democratic period have been steadily winnowed away. Progressive taxation, which was intended to ensure those who made more money paid a higher percentage of taxes has been hilariously inverted so that billionaires pay a lower tax rate than their secretaries, so that now the middle class actually have the highest tax burden. Minimum wage, which was intended to ensure that anyone who worked forty hours a week stayed above poverty level, hasn’t increased since 2007. Social Security, which likewise was intended to be a living wage, is now a shadow of that. Medicare and Medicare are both being steadily privatized through plans like Medicare Advantage, which scams both enrollees and taxpayers. Biden has meanwhile continued a further privatization of Medicare pilot started by the Trump administration. Another Democratic president replaced welfare for the poor with ‘workfare’ and slashed its payouts. Republicans are even now proposing repealing child labor laws. And so on, as regulations and so-called ‘entitlements’ that were so hard-won have been peeled back. And rich plutocrats constantly scheme about how they can get rid of all these things, forming “think tanks” like the Peter G. Peterson Foundation which spends fortunes to convince the media to convince us that Medicare and Social Security are insoluble and will create a deficit that will bankrupt us, meanwhile the same people who fund that foundation cheered when Trump massively cut all their taxes, causing the deficit to balloon to never-before-seen highs. Almost as if it was always a lie all along to benefit the rich and powerful at the expense of everyone else. Almost as if it was always a con.

To justify their tax cuts, the rich will repeat the Ferengi-esque mantra that ‘taxation is theft’. But if you think taking some money from rich people and using it to feed the starving or give health care to the dying is morally wrong, then you value property rights over human rights.

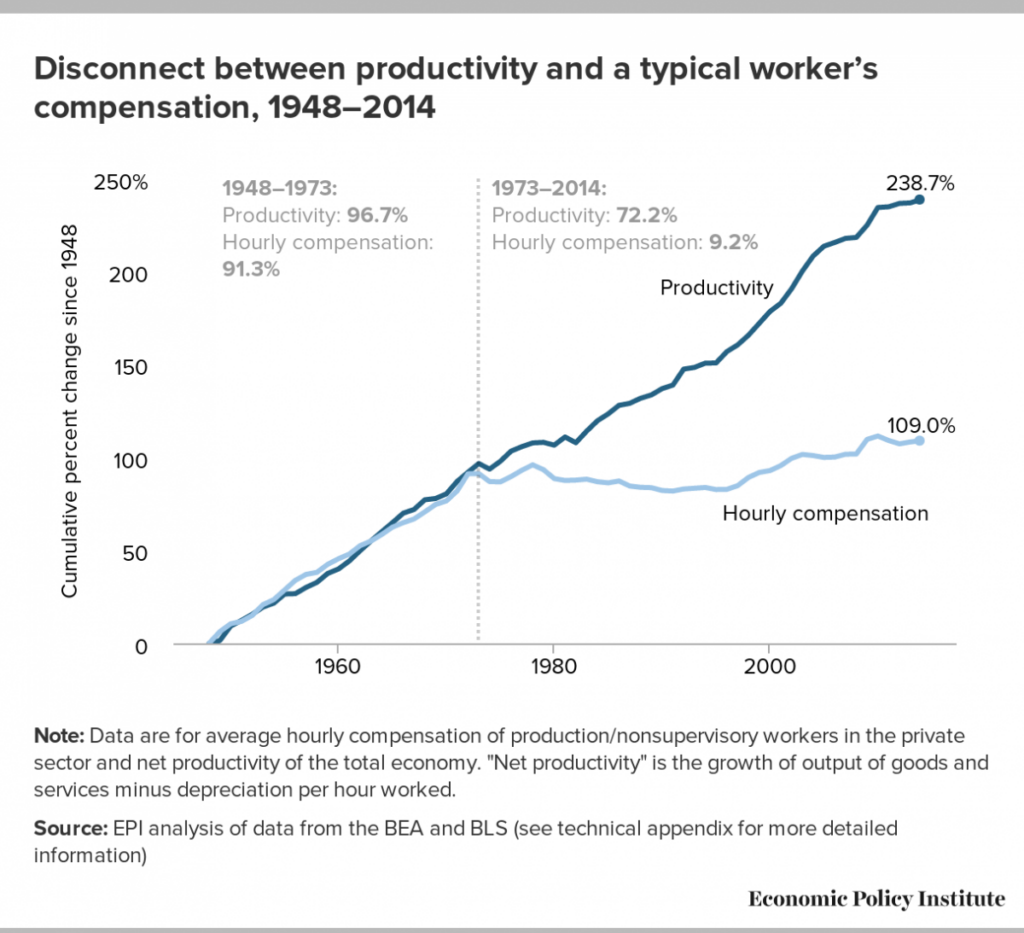

Back in 1930, John Maynard Keyes had predicted that in the future, as productivity increased, we’d be working four hour days. Instead, as productivity has skyrocketed, hours have remained the same or even gotten worse and wages went from matching productivity to stagnating right as America’s Neoliberal turn took place. From there, all the extra revenue generated by that added productivity has been captured entirely by the 1%.

This is what was stolen from us.

Today, there are far, far more empty houses than homeless people and we have enough food for everyone but people still starve. This is a moral calamity that we refuse to even admit to, and contrary to capitalist predictions, the last forty years of Neoliberal deregulation and tax cuts has only made the poor poorer and the middle class smaller.

Today 64% of Americans are living paycheck-to-paycheck and 63% of Americans don’t have enough savings to cover a $500 emergency. America is now the only developed country where people go bankrupt from medical expenses, where people literally die because they can’t afford insulin. At the same time, 2021 was the most profitable year for American corporations since 1950 and during the pandemic American billionaires got 62% richer. CEOs of large corporations now make a record 399 times the pay of their average workers while 48% of workers in the US make less than $31,000 a year.

We find ourselves once again in a time of record inflation, with wages not rising nearly as fast as the cost of goods, so that working people find themselves with the equivalent of constant wage reductions. And the Neoliberal plan to battle this is a Reagan-style “Volker Shock”, where interest rates get raised in hopes of crippling the economy and preventing wage increases (after all, nothing reduces worker’s bargaining power like mass unemployment). They’ve even advised companies not to raise worker wages in the face of crushing cost of living increases. This is their best plan.

And yet while politicians and pundits blame inflation on stimulus money that actually helped workers, or supply chain issues, or the war in Ukraine, corporations rake in record profits proving that underlying conditions are not the primary cause at all but corporate greed and opportunism. As Bernie Sanders pointed out, if the oil price per barrel today is the same as it was in 2010, and yet gas is selling a dollar more per gallon, that price isn’t the result of underlying conditions. There’s a reason Shell Oil reported more than double profits in the third quarter last year as in the same quarter the year before. Corporate profits reached an all-time high of $2.5 trillion last year while real wages declined more than 8.5%.

Capitalism has never worked.

Allowing a few people to own housing and charge however much rent they want for it, or to own a business and treat and pay their workers however they can get away with, is a disaster for human wellbeing. We can do better than Amazon warehouse workers peeing in bottles, suicide nets at Foxconn factories, and mentally ill people freezing to death on street corners. If an alien came down to Earth and you explained it to them, they could tell you how highly illogical this all is.

In Star Trek’s own diegetic history, the path to the end of capitalism begins when, following a cataclysmic Third World War and international governmental collapse, scrappy genius Zephyr Cochran and his team create the Earth’s first warp drive. This attracts the attention of the Vulcans, who come down and help usher in a new age. In real life, though, we can’t rely on heroic leaders to save us any more then we can rely on benevolent aliens, nor can we sit around waiting for an eschaton or collapse to fall upon us in hopes we’ll survive long enough to build something better in the ruins.

Of course, it’s difficult to even imagine substantial change in the American government today due to its sheer disfunction, undemocratic institutions, and corruption. The House of Representatives is undemocratic because of gerrymandering, the Senate is undemocratic by design, and the presidency is undemocratic thanks to the electoral college. And that’s not even mentioning intentional voter suppression and the ongoing campaign to take over and subvert the mechanisms of elections, which contrary to the popular narrative dates back long before Donald Trump’s “Big Lie”. More importantly, our government is corrupt to its bones, thanks to the legalized bribery of campaign spending. How can we expect politicians to raise taxes on their own campaign donors, or to advocate for policies that disempower them? Hell, we even give rich people tax breaks to donate to the so-called “think tanks” that lobby for legislation that favors them, instead of their money actually going to the public good. Over half of the members of congress are millionaires themselves. Should we be surprised when they look after their own class interests? Like should we be surprised when Nancy Pelosi defends the practice of trading stocks whose value depends on her own policies, when this practice personally makes her millions?

Further, democracy depends on freedom of the press, and yet how free is our press if its controlled by a small number of the ultra-rich as part of ever larger conglomerates, funded by advertising from other ever larger conglomerates. Is it a surprise we get pundit after pundit in the news media decrying even the backwards-looking proposals of Sanders and Warren as ‘socialism’ and therefore bad and wrong and evil? Is it really a surprise that an obvious fascist like Tucker Carlson gets a popular TV show while there isn’t a single genuine leftist on television? This isn’t a conspiracy, media moguls aren’t gathered in a room plotting to keep the working man down. It’s a simple case of class interests and, as economists are fond of saying, incentives. Meanwhile the right continues to laughably portray the ‘mainstream media’ as ‘left wing’ by playing up their bigoted “Woke” Culture War bullshit. The result is what philosopher Antonio Gramci called a cultural hegemony that renders any more egalitarian way of doing things not only evil but unimaginable. Capitalism, despite being only a few hundred years old, is portrayed as a state of nature from which there is no alternative. Or, as my father used to paraphrase Winston Churchill, capitalism is the worst system except for all the other ones, which renders capitalism essentially beyond criticism. Hence the expression ‘it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism’. Capitalist billionaires riding around in big dick rockets want you to think that they’re the ticket to a Star Trek future, that they’re going to invent it for us. But the truth is that we could create the means to end scarcity tomorrow, we could just have Star Trek replicators come out of a lab somewhere, and those same billionaires would make sure we artificially limited and metered its output so that they could extract profits from it. They’re not creating the future, they’re standing in its way.

As I explored in my Loki episode, the same conditions that created socialist political change during the Great Depression also created the conditions for the rise of fascism, and the wealthy will invariably choose fascism over socialism because fascists will let them keep their private property. (Anytime someone tells you the “National Socialists” were actually socialist, show them how they were bankrolled by the rich and powerful.) And they’ll tell us this is for our own good because it prevents “mob rule”, which is just a euphemism for poor people having opinions above their station.

And even that just scratches the surface of the ways the rich dictate policy. Like, did you know there was this DA in San Francisco whose policies worked against the interest of real estate developers, and those real estate developers and their finance chums spent seven million dollars on a successful smear campaign to have him recalled? This despite his policies being shown to work and be popular?

A study in 2014 confirmed suspicion that economic elites and business interests have a massive effect on public policy, while the preferences of average citizens have little or no influence. But we don’t need a study to see this when it’s in front of our face, a majority of Americans favor a wealth tax on the rich, Medicare for All, codifying Roe v. Wade, paid maternity leave, raising the minimum wage, government funded childcare, free public college, and so on.

And our enemies point to the disfunction and corruption they themselves work to create and maintain and tell us this is why government is bad and we should just trust undemocratic corporations to govern themselves, while they happily hand out our money to those same corporations in the form of tax breaks, subsidies, and bail outs. But tell me again how capitalism benefits everyone.

Of course, one wing of the socialist movement will tell us the solution, the only real solution, is violent revolution. It’s easy to see the logic of their viewpoint, to conclude that if you’re barreling towards a cliff and the bus driver won’t listen to reason, you need to just lop off their head and take the wheel. But, even putting aside the danger of falling into an authoritarian trap à la Lenin, and putting aside the piles of of dead innocents that every violent revolution in history has produced, to have a violent revolution you need to have what Lenin himself called a ‘revolutionary situation’. Russia at the time of the Bolshevik Revolution was beset by mass starvation, poverty, and warfare, and thus had a population desperate enough to risk death for the sake of change. At least in most of the west we’re simply not there yet, and honestly we wouldn’t want to be if we have a choice. So, let’s instead look to options that don’t require breaking out the guillotines.

As we’ve seen in the example from Roosevelt and the New Deal, mass movement and organization can force changes in policy. There’s evidence that merely getting 3.5% of the population to peacefully demonstrate can force political change. The constant cycles of economic crisis since the onset of Neoliberalism have created an upsurge in interest in unions and socialist organizations not seen since the Depression. But what specifically should we be fighting for?

One obvious answer is to try and reclaim what we once had, to rebuild the protections and programs that existed before the Neoliberal era. And that’s a lot of what Democrats propose–it’s even in the language that gets used, like “The Green New Deal”, and “Build Back Better”. Even new programs like Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All” is both the expansion of an earlier program and the realization of the universal health care that Franklin Roosevelt tried to establish back in the 30s, which would merely bring us up to parity with most of the rest of the developed world. There’s an almost reactionary pining for a golden age of the past when you watch someone like Elizabeth Warren talk about everything the Neoliberals have stripped away. They point, with justification, to the Scandinavian countries and their “Nordic Model” that has given them the highest levels of happiness in the world. The rhetoric here is often that we need to rebuild the social-democratic compromise so that we can ‘save capitalism’.

The problem with the social democratic compromise is that by permitting capitalists to keep accruing as much power as they can, they’ll inevitably turn and try to destroy the social democracy for their own gain, just as they’ve done since the dawning of the Neoliberal era. Even in places like Sweden, capitalists have been stripping apart the hard-won social safety network for parts. You haven’t solved the problem, you’ve just kicked the can down the road. Given the magnitude of the issues we face and the ecological collapse on the horizon, it’s clear we need change of a more fundamental nature and we need it urgently.

One option frequently bandied about is Universal Basic Income. This idea has a lot to recommend it. Every person, regardless of income, would receive a flat payment from the government. By making it universal and not means based, you ensure there isn’t a benefit cliff, where someone starts making more money and actually loses money. Instead you simply take back money from the wealthy through higher taxes. Also because the middle class receives it rather than just the poor, it becomes much harder to take it away later.

If this payment were an actual living wage, you might have found the easiest way to Federation-style freedom. People could spend their lives doing the things that actually gave their lives meaning, and actually essential functions would get done because if they’re actually essential the jobs would pay enough to make it worth someone’s while.

Various real-life experiments have shown that UBI produced great results. However, it has fundamental problems (none of which are “how would we pay for it” when no one asks how we pay for ever-ballooning military spending increases and tax cuts for the rich). The corporate-controlled congress could easily make the payment far less than a living wage and then use it as justification for cutting other social services that people might depend on that give more. In this scenario, it’d be easy for corporations to lobby for eliminating minimum wage and paying workers far less, resulting in greater profits for rich business owners, while since the UBI still wouldn’t be enough to live off of, workers would still need to keep terrible jobs on threat of homelessness and starvation. In other words, rather than a support system for the people, it’d simply become a gift to the payroll costs of employers, a mass subsidy for corporate capitalism and, given the current tax structure, one substantially paid for by the middle class. In fact, we can already see that happening with welfare programs here, where companies like Walmart intentionally pay employees too little to live on and then gives them instructions for applying for welfare. Who is this Welfare meant to actually be benefiting, exactly? And at worst, with UBI and welfare you can end up with an underclass of people automated out of their jobs with no opportunities for anything better, living off a barely subsistent UBI, piled high in godawful housing like in something out of Ready Player One. Meanwhile, the rich would still be living high off the hog in a world built just for them, while dismissing the unemployed as ‘lazy’.

This is not socialism.

Which is to say that UBI and welfare more generally are good ideas worth doing, but still wildly insufficient on their own. For a different strategy, let’s look at the most ambitious democratic socialist policy ever attempted. In the 70s, Sweden formulated something called the Meidner Plan for Wage Earner Funds. Essentially, a percentage of profits from for-profit companies would be used to buy shares of public Swedish companies, with those shares being placed in funds controlled by unions. Thus, ultimately the entire economy would transition to almost total worker-ownership within a few decades. Capitalists, to put it lightly, did not like this plan, and used their considerable resources to organize the largest demonstration against it in Swedish history. By the time it had been implemented in 1984, the tax to fund it had been starkly reduced and it had provisions to specifically weaken worker control. In 1991, the right wing took control of the government and ended the plan entirely, privatizing the funds. In fact, Sweden then followed Norway’s lead into partially privatizing their pension funds. At first glance, this might seem like using the government’s money to own segments of the private economy, but in practice this is simply like the plans to privatize social security in the US, a way of funneling tax money into the hands of private business owners while giving the people little say or interest in the actual management of the companies themselves. 401k plans were touted over pensions as giving average Americans a stake in the economy, but without a mechanism for collectively exercising any power over the corporations 401ks are invested in, all this amounted to was a giveaway of wage earner money to corporations, while employees lost the guaranteed pensions they once had in favor of plans that are chronically underfunded and insufficient.

Other, less ambitious policies can increase cooperative ownership of businesses. For example, in 1985, Italy passed the Macora Law which allows unemployed workers to get advances on unemployment benefits and pool them together with other workers to start worker cooperatives. This scheme has so far created 257 cooperatives involving 9,300 worker-owners. In the US, Bernie Sanders recently got legislation passed to allow coops to receive SBA loans and funding nonprofits to aid and advise people on creating and managing coops. There’s also been local efforts to support cooperatives, for example many municipalities in California have enacted legislation to aid the creation of cooperatives and help employees purchase businesses from their employers. But compared to the Meidner plan all of these are tiny, incremental drops in the bucket in the face of the enormous, multinational conglomerates that dominate the global economy for the sake of their billionaire masters.

People often use the term ‘radical’ these days as a way to write off someone’s ideas, anything ‘radical’ implied to be not sensible, or practical, or valid. But sometimes radical change is called for. Sometimes its necessary.

To illustrate all of this, let’s turn one final time to Star Trek and one of the best episodes they ever did about class inequality. In the Deep Space Nine episode “Past Tense”, members of the crew travel back to the mid-21st century, two of whom find themselves in a walled-off encampment for the homeless and unemployed amid rampant inequality. This encampment is in an area with apartments, so there’s housing of a sort, but of course it’s run down, unmaintained, and there’s too little of it. There’s food, but not enough and it’s spoiled and awful. In other words, this is the nightmare scenario of UBI, where the surplus poor are given just enough to be kept alive and tucked out of sight. When the people of the encampment rise up in a riot, Commander Sisko finds himself taking part in a hostage situation, demanding Federal jobs and ‘not handouts’ (like the Civil Works Administration of the New Deal which funded infrastructure projects as a mass employment strategy). Finally, Sisko engineers a way for the people of the encampment to tell their stories through the global network, beginning the process of America “correcting the social problems it had struggled with for over a hundred years”. Without this incident, we discover, the Federation will not come to be.

It’s true that this story still has a focus on a heroic individual doing work to bring about change, and there’s even an element where Dax must convince a wealthy businessman to help them get access to the network that will let them share their stories. But the overall story is about the people engaging in mass action to take control of their lives.

One might expect somebody in the story to be talking directly about capitalism, to be complaining about the corporations that dominate society and the rich in their penthouses while ordinary people starve, but DS9 in 1995 can’t be so direct without coming off preachy and overbearing, and without alienating much of an audience steeped in the cultural hegemony of Neoliberal capitalism. But the show is still firmly on the side of the disenfranchised, of homeless, hostage taking rioters in a way rarely seen on mainstream television then or now (especially considering how politically toothless modern Star Trek has generally become). This isn’t some Marvel-style commentary where the villains have noble aims irredeemably marred by immoral means. In the story, even the wealthy are portrayed in a sympathetic light, which helps hammer home the idea that no one person is responsible for any of this. The problem is the system itself. And unless the system is changed, nothing will change. And it believes with all it’s blessedly optimistic Trekkie heart that this change is possible if only we work together to create it.

We must continue focusing on organization, on building up unions, cooperatives, mutual aid groups, and actually left wing political organizations. And we must use the power of those organizations to demand real, substantive change in the structure of the economy through ideas like the Meidner plan and policies to increase the prevalence and power of unions and worker coops, as well as electoral reform to increase the democratic character of the state itself to make further change less difficult. And, as I’ve said, we must do all of this while being vigilant against the ever-present threat of an authoritarian seizure of power from the right, one currently being actively pursued with the steady takeover of electoral institutions.

Fittingly, in contrast to the typical television format where the best lines are always given to the leads, the best line in “Past Tense” is said by one of the supporting characters, some common ‘nobody’ who’d never be seen on the show again. At one point, a hostage relates a story about a woman at the encampment she regrets she couldn’t help more. Doctor Bashir tells her, “It’s not your fault that things are the way they are.” And she replies, “Everybody tells themselves that, and nothing ever changes.”

Let’s see if maybe we can change things.

—

Well. That took a long time to make. This was one of the most difficult episodes for me to write because of the amount of research I did and how I wanted to make sure I got it right and gave these ideas their due. By my notes, this is the fourteenth draft of this thing. Early drafts had long digressions into what happened in the Russian Revolution and Civil War, and an in depth exploration of Democratic Socialist thinker Eduard Bernstein and his ideas. His story is still fascinating to me in all sorts of ways and something I hope to come back to in the future. But all that, ultimately, seemed to distract from the central point I was trying to make. Also my family all finally got Covid during the production of this one, so that took a bit of the wind out of its sails especially since I was in the middle of recording the audio and then found myself with a persistent hoarseness.

This is liable to be one of my most controversial episodes (the comment section is liable to be cancer), but I hope even if you disagree with me I’ve given you something new to think about. I’ve done so many videos already criticizing capitalism, and will do many more in the future, that I felt like I had to be able to answer the objection that capitalism may be bad but no viable alternative exists, which is the narrative capitalists have been feeding us in the west for decades now.

For those who might be wondering when I’ll get back to episodes of a more reasonable length, I’m planning on some shorter, more frequent ones next so be sure to subscribe, and hit that like button! Do you prefer longer or shorter episodes? Let me know in the comments. I’m really curious, actually.

You can support this project on Patreon at patreon.com/ericrosenfield, and for as little as $1 an episode get access to exclusive show notes and early access to episodes. (That’s like $1 a year the way I’ve been doing things, surely you can afford that.) I’ll even put up there some of the digressions I mentioned. As always I’d like to thank my patrons, Jason Quackenbush, Industrial Robot, Wilma Ezekowitz, Benjamin Pence, Kevin Cafferty, Hristo Kolev, Gabi Ghita, Arthur Rosenfield, and Nancy Rosen. Thanks!

Special thanks for input and help with this episode goes to Aristide Twain and Hidden Behind the Sun.

Literate Machine is available as a YouTube channel, podcast, and newsletter. For more information, visit LiterateMachine.com.

Bibliography and Further Reading

- Obviously, the work of Marx and Engels is key to this piece. Particular texts I drew on here include The Civil War in France (1871) (modern editions contain the first draft and the address on the Civil War) and The Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875). Marx’s La Liberte speech (1872) is where he proposes that some countries might transition to communism peacefully: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1872/09/08.htm

- One of my chief inspirations for this piece and in general is the book Socialism: Past and Future (1989) by Michael Harrington, founder of the Democratic Socialists of America. Socialism does a good job of summing up the history of socialism, the rise of democratic socialism, the problems we faced in the 20th century, and where we might go from here.

- The Preconditions of Socialism (1899) (also published in English as Evolutionary Socialism) by Eduard Bernstein is a fascinating book by the father of the democratic socialist movement and the idea of achieving socialists goals through gradual reform. A controversial figure both in his time and today, both with orthodox Marxists and modern democratic socialists, his story is one I find endlessly fascinating. Much as during the Social Democratic period of the mid-20th century, when Preconditions was first published, it seemed as if gradual socialism was working in Bernstein’s native Germany. Then of course the First World War brought Germany to its knees. Bernstein himself, who’d become a member of the Reichstag, would die three weeks before Hitler came to power, undid all the achievements of his party, executed its leaders, and most of the members of Bernstein’s ethnic group. While researching this piece, I also drew on The Dilemma of Democratic Socialism: Eduard Bernstein’s Challenge to Marx (1952) by Peter Gay, and the excellent introduction to the English translation of Preconditions from 1993 by translator Henry Tudor.

- For the history of the Russian Revolution, I highly recommend China Mieville’s October (2017), a highly readable retelling of the story of the revolution and the events around it.

- I am highly indebted to the work of Richard Wolff, whose Democracy at Work (2012) and associated website and YouTube channel opened my eyes to the possibilities of worker cooperatives as a tool for workers to control the means of production within a capitalist society and so create a mechanism not only to improve the lives of workers in the near term, but to build up worker power and control in the long term.

- I’m also indebted to the continued work of Cory Doctorow in and out of his Pluralistic project, with too many useful and informative pieces to list here. For example, Pluristic turned me onto how municipal broadband providers are the only ones with consistent customer satisfaction, or his piece in Boing Boing about how the notion of the “tragedy of the commons” is based on lies and fraud. Other important pieces include What Comes After Neoliberalism and Excuseflation.

- Carlos Maza’s excellent video essay “The Pay for It Scam” is essential for understanding the ways in which only programs for the social good are ever asked “how will you pay for it”, while corporate subsidies, tax cuts, and the military budget piles on the debt.

- Most of my research on Gene Roddenberry comes from the book The Impossible Happened: The Life and Work of Gene Roddenberry, Creator of Star Trek by Lance Parkin (2016)

- For more on the “primitive communism” of the Iroquois and other native tribes, I recommend The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021) by David Graeber.

- More on how modern corporations actually show the power of a centralized economy, a piece inspired by the book The People’s Republic of Walmart (2019).

- How the Reagan administration talked of “small government” while simultaneously funneling public money into corporate subsidies

- How homeownership rates are declining in the US

- The study showing that policies supported by the affluent get passed while policies only supported by ordinary people don’t.

- Social Security’s supposed problems could be solved by simply lifting the cap on Social Security tax that makes it regressive. Social Security needs more funding, not less.

- More on the Meidner Plan to use tax money to give power to workers

- More on Çatalhöyük, one of the earliest cities which appears to have been organized on an egalitarian basis

- Rosa Luxemburg wrote her thoughts on the Russian Revolution in the pamphlet The Russian Revolution (1918)

- Other sources can be found inline in the essay above

Pingback: StarTrek into Socialism: Or Who Deserves the Future - Corruption Buzz

Pingback: How will Capitalism End? The Orville, Eduard Bernstein, and What is to be Done – Literate Machine

Pingback: How Capitalism Becomes Feudalism (Severance and Technofuedalism) – Literate Machine

Pingback: Gravity’s Rainbow Over Palestine – Literate Machine